|

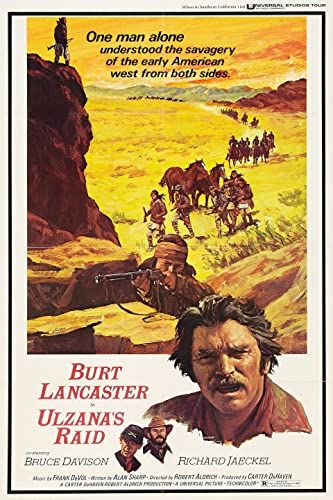

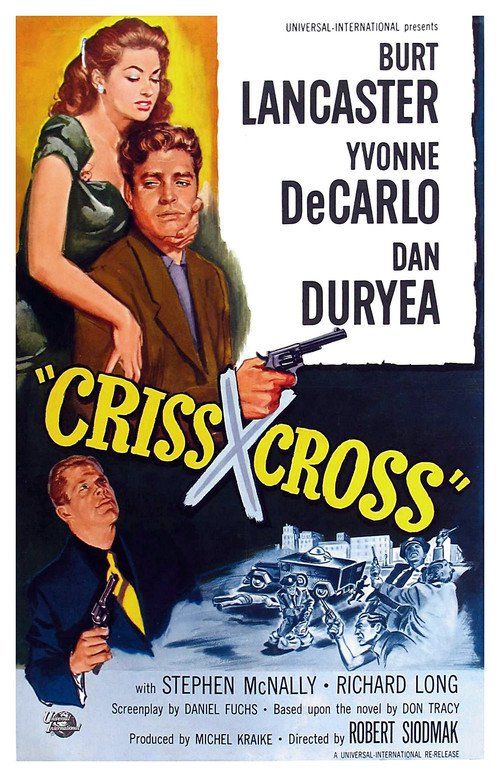

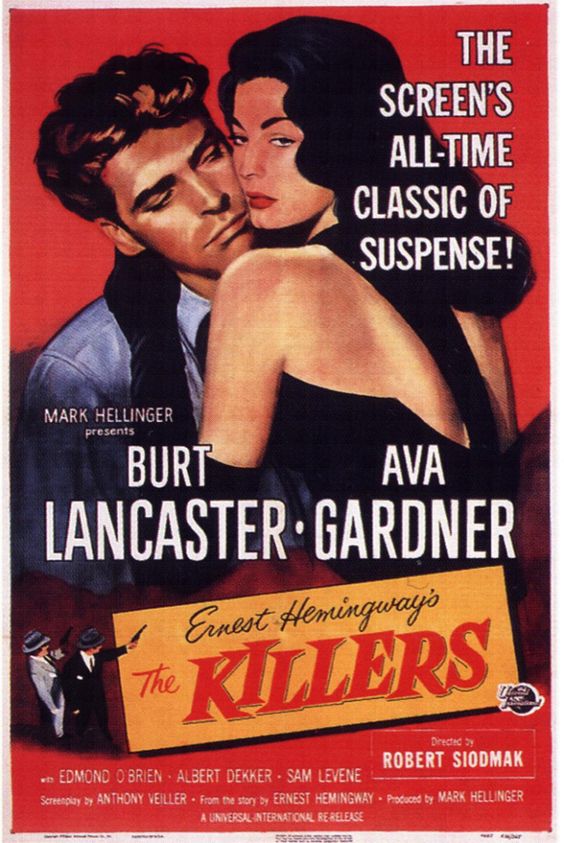

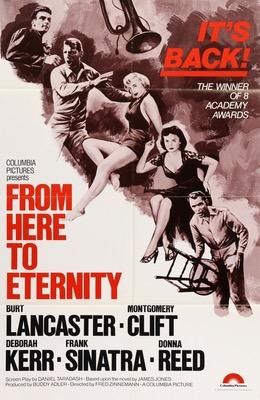

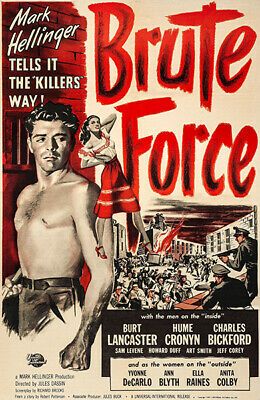

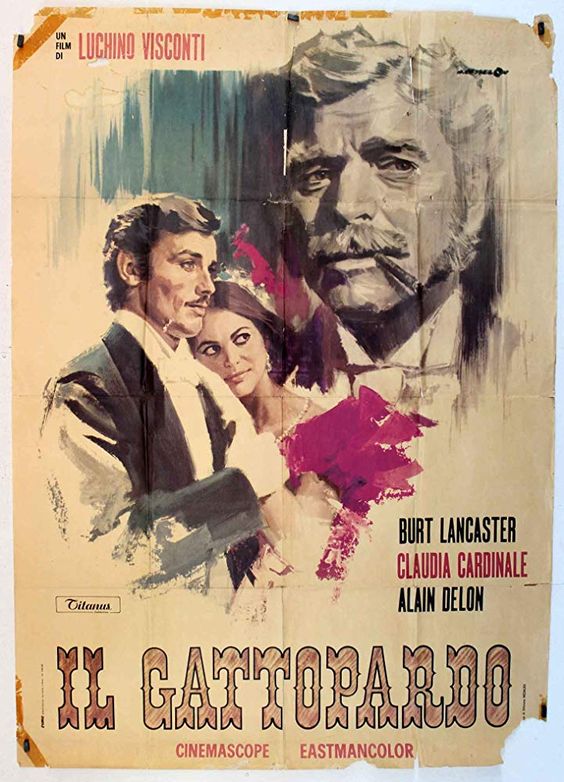

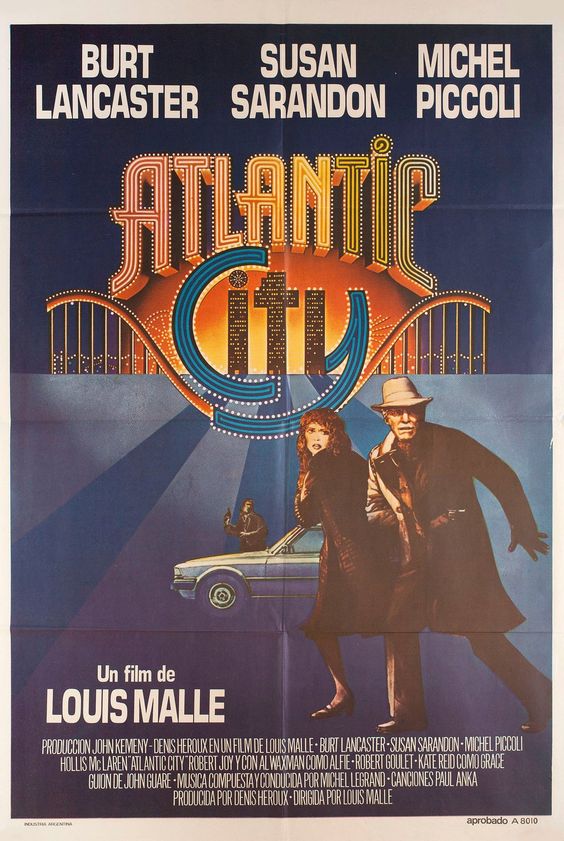

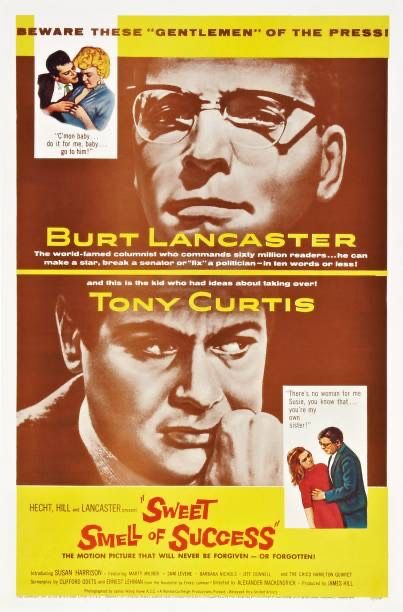

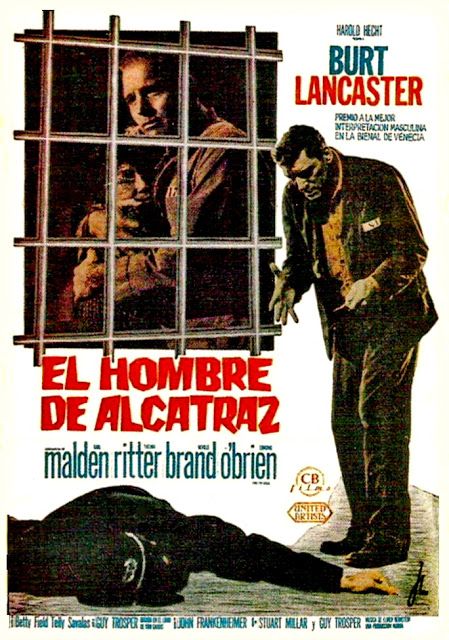

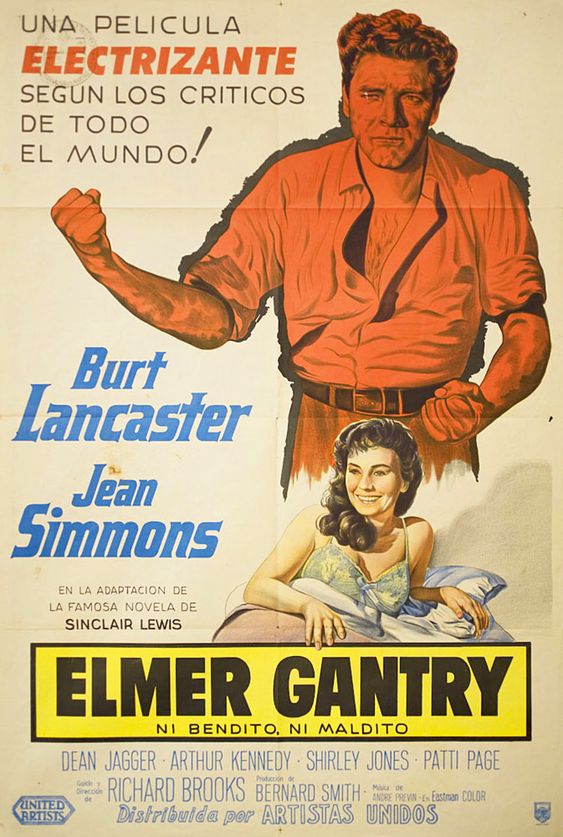

The Rationalization: Burt Lancaster skyrocketed to stardom in his first film role in The Killers (’46). He was no overnight sensation, however, because he had spent years perfecting the essence of what made his screen personae so appealing & didn’t get his first film role until he was 32. That he was able to carve out a 45 year career after starting that late is a testament to his physical appeal, his talent and his hard work. Because he had spent a good part of the 1930’s traveling with a circus as an acrobat, before enlisting & serving during WWII, Lancaster honed both the physical nature of his performance style, as well as the quiet strength that endeared him to both male & female film fans. It was a natural style that was self-taught & honed in his many performances with his acrobatic partner & best friend, Nick Cravet. Lancaster’s hulking size (he was a solid 6’2”) contrasted with his often soft spoken portrayals of good guys who often had a fatal flaw. Lancaster was also a walking contradiction in his personal life. He was a devoted family man with 5 children, married to the same woman for 35 years, but had a series of affairs. He was a shrewd business man who started his own production company just 2 years after his first film, but the company had issues managing costs. He also existed outside the studio system to a large degree, avoiding long term contracts to one studio, just as the classic studio system was dying, but remains one of the most fondly remembered actors of the classic era. Burt Lancaster is no simple man to pin down. He was complicated and challenged himself & his audience in every performance he tackled. In the end, he is also one of the greatest actors of the 20th century and the longevity & variety of his career is proof that even overnight sensations can stick around for a career! #10 Ulzana’s Raid (’72) is the 3rd in a trilogy of Western’s Lancaster made as he moved towards more mature leading man roles. While he was nearing 60 years old, Lancaster still looked & performed much younger. Along with Valdez is Coming (’71) & Lawman (‘71), the trilogy marked a subtle rebuke to the fascism of Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry (’71). Instead of showing a merciless killer, regardless of what side of the law he may be on, Lancaster’s heroes were flawed & willing to try to understand the meaning of violence & how the other side may have felt. Ulzana’s Raid, the best of the three, is the story of a cavalry troop led by an inexperienced Lieutenant (Bruce Davison) & guided by seasoned scout McIntosh (Lancaster) as they track a murderous group of Apache tribesmen, led by their chief Ulzana. As the troop is repeatedly outsmarted by the guerilla tactics of the Apache’s, it is clear there are obvious allusions to America’s issues in Vietnam. Lancaster’s McIintosh is a tolerant & understanding man who is willing to do his job, but wants to explain the Apache’s actions as opposed to blindly hunt them. Per usual, Lancaster approaches the role simply and quietly, using his size to speak for itself & subtle gestures & looks to convey his deep knowledge & understanding of the character. When asked years later which of his many characters was closest to his person views on life he mentioned McIntosh. The superficial calm of Lancaster’s performance covered a raging battle between the actor & director Robert Aldrich (The Dirty Dozen ’67, Kiss Me, Deadly ’55). Aldrich wasn’t as interested in making the film an allegory about Vietnam, but in the end Lancaster was able to make the small edits he felt brought the point home. Finally, in explaining his acting technique to co-star Davison, Lancaster explained his quiet ways thusly: “…and your acting & acting & acting & by the time you come to your close-up you’ve shot your wad. It’s like making love to a woman: you can’t try to come all at once, son. A bit of tit here, a bit of inner thigh there, and you then have a performance.” (Buford. P. 273.) #9 Criss Cross (’49) marks the evolution of Lancaster’s performance as “the Swede” in The Killers to a character more grounded and with more potential. Made 3 years later and for the same director, Film Noir icon Robert Siodmak, both characters are somewhat simple and well-meaning, prone to let the action come to them as opposed to going to get it, but Criss Cross’ Steve Thompson has a job, a family & a future. That he falls into the same trap, because of a woman, is both terrible and marvelous at the same time. Yvonne DeCarlo, in perhaps the best performance of her career, is Steve’s ex-wife & the woman who is willing to drag him down for the bootie from a payroll heist that is one of the best in film history. Lancaster’s Thompson is an armored car driver caught in the act of fooling around with the gangster’s girl, albeit his ex-wife, & must tap dance to avoid an early grave. Slim Dundee (Dan Duryea) is one of the most menacing & intelligent bad guys in the Noir canon, so it’s no simple task for Thompson to plan & execute the heist, while keeping Slims suspicions grounded. Lancaster plays Thompson as a frustrated lover, sick & tired of always getting the short end of the stick with Anna (DeCarlo). He’s a momma’s boy with a healthy libido, but as Lancaster plays him, neither his anger nor his Pollyanna attitude gets the better of his scheming to outthink the gangster. DeCarlo’s femme fatale is also one of Noir’s best & both she & Slim keep Steve guessing until the final shot. To paraphrase Eddie Muller, the Czar of Noir: “What happens when the double crosser gets double crossed? You have a criss cross.” #8 The Killers (’46) Burt Lancaster, acrobat, was summoned to Hollywood for a screen test by producer Hal Wallis (Casablanca ’42, Now Voyager ’42 & The Strange Loves of Martha Ivers ’46), who had an independent company set up at Paramount. Lizbeth Scott (I Walk Alone ’47 & The Racket ’51) co-starred with Lancaster in the test & said he was one of the best looking boys she’d ever seen (Buford p.64), while director Robert Wise (Sound of Music ’65 & West Side Story ’61) note that Lancaster “had a gene for the screen.” (ibid). Wallis signed Lancaster to a contract that paid him $250 a week & renamed him Stuart Chase. It took Wallis’ assistant, however, to finally get Lancaster’s career on the move when she sent fellow independent producer Mark Hellinger the screen test 6 months later for a little picture he was making called The Killers, based on a short story by Ernest Hemmingway (and a screenplay worked on by an uncredited John Huston). Hellinger would pay him $20,000 to play the Swede & to make him a star. Hemmingway’s story is no more than 2 pages long & focusses on 2 hit men killing a character known only as “the big Swede.” The opening scene of the film is the whole of the Hemmingway story, with the remainder of Lancaster’s performance told in flashback of a payroll heist, a double cross, a whole lot of missing money & one of the greatest femme fatale’s ever put on screen. Strangely enough, The Killers not only launched Lancaster’s career, but as the duplicitous Kitty Collins, Ava Gardner similarly rocketed to super stardom after 6 years of mostly minor roles on MGM’s payroll. The scenes between Lancaster & Gardner are electric as the 2, soon to be mega stars, generate sexual heat & on-screen chemistry as the star crossed lovers. Lancaster is a retired boxer transfixed by the gangster’s moll he meets at a party (a scene which not only introduces Kitty, but Lancaster’s deer in the headlights performance is among the best in the film). Even a stretch in jail to protect Kitty doesn’t sour The Swede’s passion for this bad girl. Similar to Criss Cross, Lancaster plays The Swede as a little dimwitted, slow on the uptake, but loyal to a fault to the woman he loves. He is a puppy dog in the shadow of a cool & heartless mistress, yet the performance is long on nuance & subtlety rendered small moments, like when Kittyy is seductively curled up on the bed as the gangsters plan the heist. The Swede’s longing is palpable as he struggles with all his will not to take her then & there. The Killers is one of my favorite Films Noir & a great film, but even as the launching pad for Lancaster’s career, I can rank it no higher, so strong are the films that follow! #7 From Here to Eternity (’53) One of the most famous love scenes in film history is at the center of From Here to Eternity, but it’s the balance of strength of character & tender romantic that fuels Lancaster’s performance in this 8-time Oscar winning classic. That Lancaster received his first Best Actor Oscar nominee for the tough, but fair Sgt. Milton Warden is not surprising, given that the plot, to a fair degree, revolved around the Sgt. Seven years into his career, Lancaster was able to command center stage amongst an all-star cast, including Frank Sinatra, Montgomary Clift, Donna Reed & Deborah Kerr. His performance is iconic in it steady resolve, reflecting post-war American sentiment towards our role in the world. Even the famous scene in the surf with Kerr presented an opportunity for Lancaster to stretch as an actor by creating a real & emotional adult scene of raw eroticism (a coup during the prudish Production Code era). Director Fred Zinnemann (High Noon ’52, Oklahoma! ’55) worked Lancaster to ensure the button downed Sergeant was as crisp on the page as he was on the screen. Time magazine summed up Lancaster’s performance perfectly by stating “As Sergeant Warren [he] is the model of a man among men, absolutely convincing in an instinctive awareness of the subtle, elaborate structure of force & honor on which male society is based.” (Buford p.130) #6 Brute Force (’47) is a cold & hard movie, with men reduced to their baser instincts of survival in a rotten prison. While it was the 4th film that he shot, after The Killers, I Walk Alone (’47) & Desert Fury (’47), Brute Force was the second Burt Lancaster film to hit theater & Lancaster acted the star during production, intimidating actors, the crew & director Jules Dassin. What he got away with in terms of unpleasantness on set he more than translated into the confident leader of the escape plan. Later, Lancaster attributed his attitude on set to his commitment to his craft. (Gary Fishgall p. 620. If Ava Gardner’s Kitty Collins allowed Lancaster to play opposite one of the greatest femme fatales, then Hume Cronyn’s Captain Munsey gave him the perfect evil foil to match wits. The sadistic Munsey abuses prisoners for pleasure and picks on the weakest of the lot. Cronyn’s diminutive size, compared to Lancaster’s bulk provided little sympathy for Munsey, but their scenes together are the best in the picture, with each actor pushing the other towards controlled rage & all out hatred. #5 The Leopard (’63). As Lancaster aged he looked for challenges in his career and for several years made films in Europe & by European directors like Louis Malle, Bernardo Bertolucci & in the case of The Leopard, Luchino Visconti (Rocco & His Brothers ’60, Death in Venice ’71). Lancaster plays the titular character, the patriarch of a post-war Italian aristocratic family, as a man who exists solely in the past. Visconti described the character as “a very complex character-at times autocratic, rude, strong; at times romantic, understanding, sometimes even stupid and above all, mysterious” (Buford, p. 221). While Lancaster shared many of these same traits, making the film was a difficult burden as Visconti, an Italian from noble birth, saw the Leopard as a reflection of himself & place severe demands on Lancaster, who was never sure he wanted to cast. Visconti at first ignored Lancaster, forcing the star to create the part on his own, but Lancaster ignored him & used the snub to align himself with Italian aristocracy nearby the filming locations, building his character authentically. The scene around the ball are some of the most exquisite shots ever captured by Visconti and are a feast for the eyes, as the 48 year old Lancaster playing the Leopard much older glides and commands the entire room. During the late night shooting of the scene Lancaster finally broke & screamed at the director to tell him what he wanted. Visconti respected the gesture & the 2 formed a bond that carried over to the director’s penultimate film, Conversation Piece (’74). That things remembered are central to the plot allows Lancaster’s performance to be regal, in addition to the elements ascribed by Vistonti, giving it the gravitas needed to pull off the Leopard. Make sure you see the 185 minute cut of the film because it was hacked to 165 minutes for American release & while the longer version won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, the film was savaged in the US. Visconti disowned the US version (which was edited by Sydney Pollack). #4 Atlantic City (’80) Unlike some of Lancaster’s best work done later in his life that was not appreciated at the time (The Leopard, Conversation Piece, Ulzana’s Raid), Louis Malle’s Atlantic City gave Lancaster the platform & the vehicle to show everyone that he was still at the peak of his powers, even as he approached his 70th birthday. He received the final of his 4 acting Oscar nominations (19 years after his last nom.) for his portrayal of Lou Pascal, a washed up, over the hill small time wannabe gangster, smitten by a beautiful waitress/dealer in a boardwalk casino (Susan Sarandon). When stolen cocaine falls into their laps, Lou attempts to be the big man/gangster who move the drugs, but death surrounds the multiple loser. I love this performance because it’s like if Lancaster’s characters from The Killers or Criss Cross were still alive they may have ended up in Atlantic City, desperately holding on to memories of glory days half imagined. The weight of that imagination clearly lays heavy on Lou’s shoulders & Lancaster’s performance makes you feel that oppression, especially in his dealing with his dead gangster boss’ moll Grace Pinza (Kate Reid), who Lou is forced to wait on hand & foot, in a very demeaning & demoralizing relationship. The ending of the film is at once heartbreaking, inevitable & uplifting, all within a span of a few minutes. While Lancaster would go on to memorable roles in Local Hero (’83), Tough Guys (’86) & Field of Dreams (’89), Atlantic City should be his lasting legacy for the twilight of his career. He is that good in this film. #3 Sweet Smell of Success (’57). J. J. Hunsecker is not a nice man. He is cold & manipulative. He is vindictive & hateful. And you can’t take your eyes off him. As played by the hulking Burt Lancaster he is the picture of malevolence, cloaked in a stylish suit, narrow tie & horn-rimmed glasses. In Alexander Mackendrick’s film, with a script by Clifford Odets & Ernest Lehman, Lancaster is given a meaty role of a sinister gossip columnist in 1950’s Manhattan. Tony Curtis is a sycophant press agent at J.J.’s ever beck & call. Together, the 2 characters float on the fine line between despicable & disgusting, neither self aware enough to be witness to the daily selling of their souls. Sweet Smell of Success is about the corrupting effects of power & the seedy relationship between the press & celebrity. At its core its’ about man’s inhumanity towards his fellow man. If that sounds like a bitter pill to swallow for 2 hours of entertainment you’re not alone; audiences at the time didn’t like the sounds of it either. The film was a flop, even as it was named one of the Ten Best films of 1957 by Time magazine. What audiences missed, however, were the beautifully shot exteriors of New York at night, the razor sharp dialogue, crafted from barbed wire, & the magnificent performances by the 2 leads. Curtis & Lancaster create a 96 minute joust that culminates in a tour de force climax in Hunsecker’s apartment. Here there is no quiet approach to the character for Lancaster. He is a snake, constantly coiled to strike without notice & the performance is genius. Cinematographer James Wong Howe even went so far as to smear Vasoline on J.J.’s glasses to slightly blur them to further distort his reptilian thought process. This character is unlike any of the others on this list, but for pure evil enjoyment J.J. Hunsecker is as stunning a performance as any. #2 Birdman of Alcatraz (‘62) If Hunsecker is pure evil, then Lancaster’s portrayal of real life killer Robert Stroud, known as the Birdman of Alcatraz, takes evil and reshapes it, beyond recognition, towards simple, focused determination. Stroud was one of the most notorious prisoners in the US penal system, having killed a man in Alaska, then a guard while in prison & was sentenced to life in solitary confinement. While he ultimately served more than 43 years in solitary, he developed a caring & nurturing love for birds, eventually becoming one of the foremost experts on bird diseases. Lancaster’s performance & the movie itself only briefly deals with Stroud before prison & none of the rage and hatred is carried forward once the birds are introduced. Instead, the performance is a study in simple, small gestures, a slight smile of pleasure, a soft stroking of feathers. Lancaster transforms Stroud into a bird whisperer, calm, patient and loving, using his size as a counterbalance to the real past of the character. As he did in many of his best performances, Lancaster distills the person/character to its essence. In Birman of Alcatraz there is barely a glimmer of the man Stroud was before incarceration. It’s a tour de force performance that you cannot take your eyes off of and reflects an actor at the peak of his craft. Lancaster was so engrossed by Stroud that he immersed himself in Stroud’s letters, court cases & tried unsuccessfully to meet the convict. His primary reason for his research was to understand how & why Stroud had taken his meaningless existence in prison & recrafted it into something meaningful. The bureau of prisons didn’t take kindly towards giving Stroud’s life meaning, so they shut the production out of location shooting, with all the sets being filmed on Columbia’s backlot. So determined was Lancaster to capture the essence of the man as he saw him that he fired the film’s first director, Brit Charles Crichton (The Lavender Hill Mob ’51, A Fish Called Wanda ’88) & installed John Franenheimer, who had directed Lancaster in 1961’s The Young Savages. Together the 2 men crafted the visual squalor of the prison, but gave the performance a softness to further it from the surroundings. At one point, so immersed in his performance, Lancaster began to cry. Frankenheimer wanted to keep filming, but Lancaster stopped, noting “Let the audience cry. Not me.” (Buford, p. 210). Lancaster went on to earn his 3rd Academy Award nomination for the film, but lost to Gregory Peck in To Kill a Mockingbird. #1 Elmer Gantry (’60) Stroud’s prison transformation may have been who Lancaster wanted to be, but Elmer Gantry was the man Lancaster actually was; brash, physical, loud and commanding attention. Based on Sinclair Lewis’ controversial novel about a bombastic preacher who is brought low by his sins, most notably with a prostitute, Elmer Gantry gave Lancaster his only Academy Award for Best Actor and cemented him as an actor of great talent. In a short 12 years, Lancaster had evolved from a blank slate as an actor to one who could portray deep pools of emotion without sacrificing his superior physicality. Gantry would be the fulfillment of that transformation. Lancaster & director Richard Brooks spent 7 months crafting the adapted screenplay “brick by brick, like a wall” (Buford, p. 200). As with Birdman 2 years later, Lancaster committed himself fully to his performance, becoming Gantry on the set. While the pattern of speaking & facial expressions were the calling card of Gantry, Lancaster also added his innate physicality to the performance to overwhelm those in his presence. While Brooks & Lancaster were aware of the impact & reaction the film would generate amongst church leaders, they were careful not allow any distractions to affect them on the set. They also wanted to make sure they could make the film they imagined, complete with dialogue like Lulu Barnes’ retelling of her redemption at the hands of Gantry: “He got to howlin’ ‘Repent. Repent!’ and I got to moanin’ ‘Save me. Save me’ and the first thing I knew he rammed the fear of God right into me.” Gantry’s cynical view of religion, while couched while pursuing Sister Sharon, is also steeped in the knowledge that ‘he will remain enough of a believer to know his eternal destination is hell.” (Buford, p. 205). This balance is key to the performance & the core of the movie. Gantry teeters on the fine line between damnation & redemption, but always topples over onto the side of the devil. Lancaster brilliantly captures that high wire act in both his emotional performance & his physical gestures. He embodies the struggle, wanting what every man wants (according to Brooks) “money, sex & religion.” (Buford, p. 205). Lancaster was Gantry in every form. As an actor, as a father, as a businessman & as a man. It was his crowning achievement as an actor. In an interview after Lancaster had won his Oscar for Elmer Gantry he summed up his philosophy of acting by saying, “If what an actor has to say (in his performance) remains a mystery to people who see it, I don’t think he’s done a good job. All worthwhile creative work has a kind of universality…If it doesn’t measure up to that, then it’s not art, it’s bad.” (Buford, p. 218). Clearly, Lancaster left a bit of himself in every performance & as his career evolved he was able to give more & more. This list is not meant to be a static reflection of Lancaster’s career, I still haven’t seen many of his great movies, including The Swimmer, but it does reflect the arc of his career. Very few actors, in fact, had as long & varied career & with so many quality performances coming later in that career. Burt Lancaster was an individually fine actor, movie star and movie producer & these films reflect that uniqueness. Sources: Burt Lancaster: An American Life. Kate Buford. Alfred A. Knopf. 2000. Against Type: The Biography of Burt Lancaster. Gary Fishgall. Scribner. 1995. Ava Gardner: Love is Nothing. Lee Server. St. Martin's Press. 2006. The File on Robert Siodmak in Hollywood: 1941-1951. Joseph Greco. Dissertation.com. 1999.

1 Comment

|

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed