|

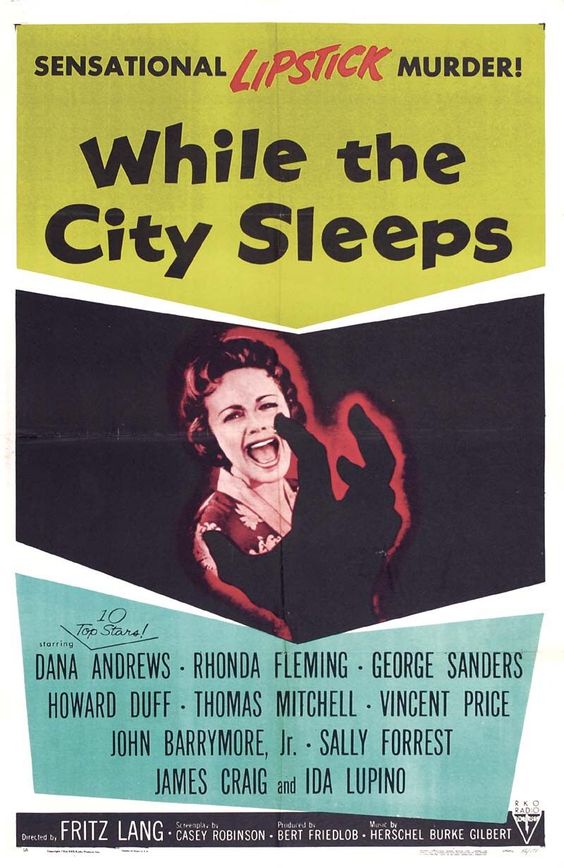

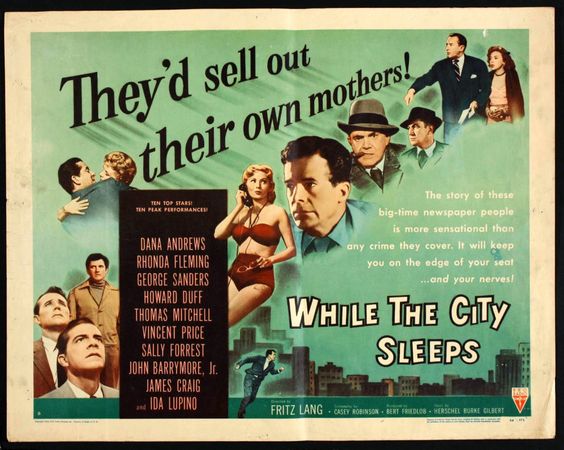

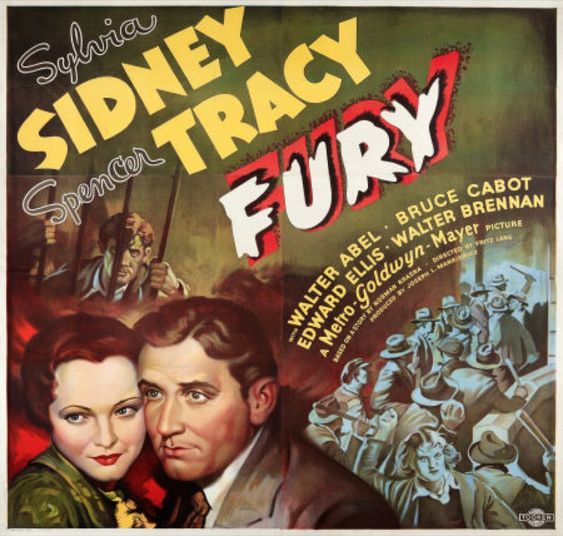

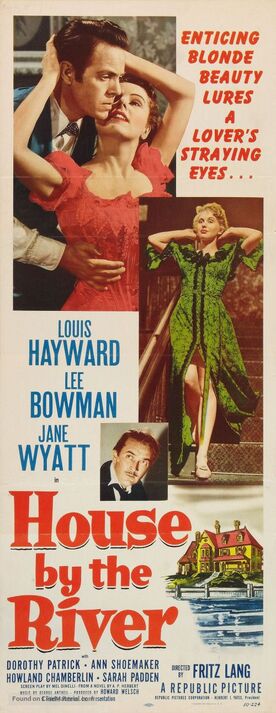

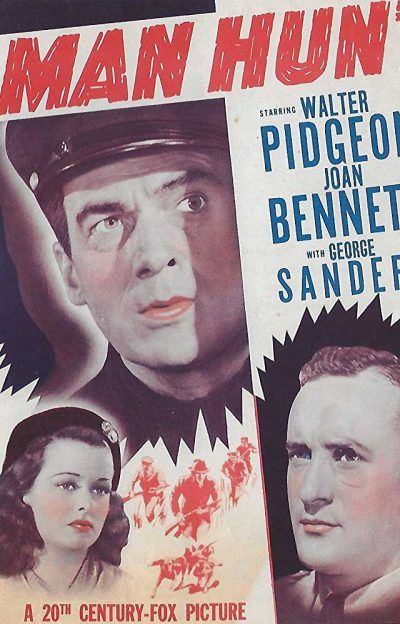

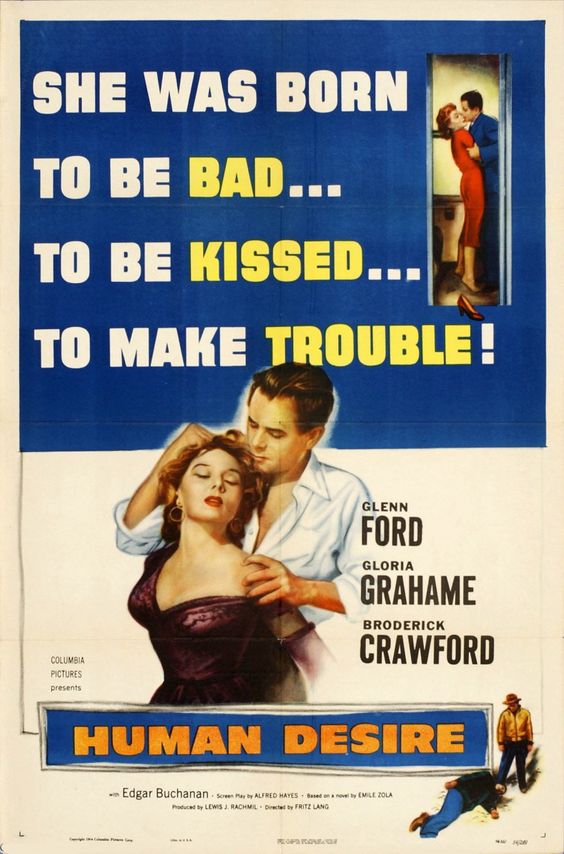

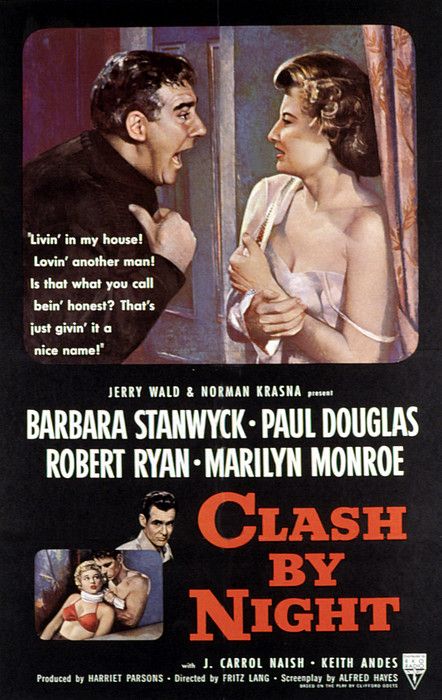

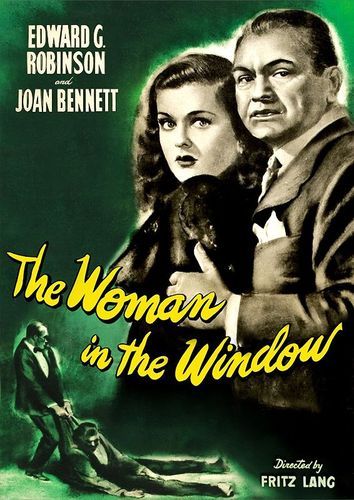

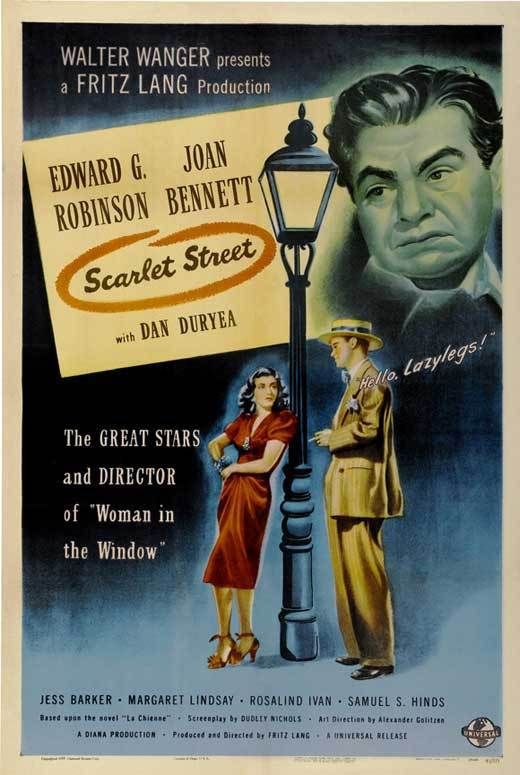

The Rationale: For as great as a director as Fritz Lang (1890-1976) was critics generally break his career down into 2 distinct periods, his German films & his American films. In Germany during the ‘20’s Fritz Lang was king. His silent films were popular & innovative & several have risen to classic status, most notably Metropolis (1927). His personal favorite, however, was his early sound masterpiece, M (1931), which, along with The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933) would be the capstones of his German films. Most, if not all of these films dealt with the same themes Lang would return to throughout his career, particularly isolation & oppression. As the Nazi’s came to power, so the story goes, Lang was given ‘an offer he couldn’t refuse’ by Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda, to be the leader of the Nazi film apparatus. Lang’s version of what happened next was a tale of his clandestine departure from Germany with little more than the clothes upon his back. According to research by Patrick McGilligan, for his comprehensive biography of Lang, Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast, Lang did not leave Germany for some 10 months after his meeting with Goebbels & did so with a good deal of his possessions, if not considerable money. Even though his 2nd wife, Thea von Harbou, his frequent scriptwriter, was a conservative nationalist & stayed in Germany, there is little to suggest that Lang did anything to aid or assist the Nazi’s while he stayed in Germany & later openly & frequently railed against Hitler & his regime. What this period of time did provide, however, is a clear delineation between his German period & his American period, because Lang made just 1 film between 1933 & 1936, Liliom (1934), which was financed & made in France. While his German films were extravagantly executed, often with unlimited budgets, & contained dynamic camera movement, expressionistic lighting & staging & visually arresting images & effects, Lang’s American films were often understated and generally contained simple, often 2 dimensional sets & workaday characters. What is consistent throughout, however, is the struggle of ordinary people, fated towards extraordinary circumstances either of their own doing or thrust upon them by an uncaring entity, be it the legal system, the government or corrupt criminal organizations. Lang’s American Films Noir particularly expressed his more cynical nature regarding his fellow humans, complete with desire, greed, avarice & malice. Foster Hirsch, in his seminal book Film Noir: The Dark Side of the Screen, singled out Lang as having “contributed more well-crafted titles to the canon (of Film Noir) than any other director.” (p. 116) #10 While the City Sleeps (1956). When Lang was interviewed by Peter Bogdanovich for his book Fritz Lang in America, Lang specifically mentioned While the City Sleeps as one his films that he liked “very, very much.” (P.19). Centering on the capture of a serial sex killer, dubbed the “lipstick killer”, the Langian cynicism is on full display as a media empire’s head pits his underlings against one another to be the first to expose the killer. Sprinkle in a little pre-marital sex, an affair, the attempted whoring of a girlfriend & the perversion/compulsion of the murderer himself, & Lang has an ink black Noir. Dana Andrews stars as columnist who at first looks to capitalize on the killing spree, then agrees to set up his love interest as bit. With a great supporting cast, including Vincent Price, ida Lupino, Thomas Mitchell, George Sanders & Rhonda Fleming, While the City Sleeps makes a very direct & spot on critique on the various forms of media that still has resonance today. #9 Fury (1936). Lang’s first film in the USA, Fury’s critique of mob mentality had to reflect on the political climate in Germnay. Spencer Tracy stars as a wrongly accused man, who through a series of coincidences, gossip & accusations ends up being held for murder & attacked in his jail cell. When the mobs fury destroys the jail cell & Tracy is thought to be dead, the story shifts to a story of revenge & redemption. Sylvia Sydney co-stars stars at Tracy’s unwavering fiancé & the moral center of the film. Lang presents the film in the direct & straightforward fashion that would become the norm for his Hollywood period, focusing on character motivation & cool emotion over extraordinary set pieces & epic scale. Fury would be the only film Lang made for MGM on his initial Hollywood contract. #8 House by the River (1950). Mining the darkest recesses of mental illness & delusion, Lang tells the story of a failed writer who murders his maid when she rebuffs his amorous advances & enlists his brother to help cover up the crime. Layering on a simmering love triangle between the brothers & the writer’s wife, House by the River is as twisted as the writer’s mind. Working independently, on a film that would eventually be distributed by minor studio Republic Pictures, Lang was still able to implement & exploit a typical Langian theme of the strong, but insane versus the good, but weak in his story of the brothers. Even with a very limited budget & second rate settings, Lang creates a foreboding sense of decay at the heart of the story, utilizing ingenious camera angles, shadow & limited lighting to cover up the limitations. While most cast & crew reported the filming was a miserable experience, Lang, an often noted monster on set, was able to squeeze every bit of interest from the story, the actors & the film as a whole. #7 Man Hunt (1941). Lang’s dislike of Hitler & the Nazi regime was never more evident in his films than in Man Hunt, in which a British aristocrat & famous big game hunter (Walter Pidgeon) has Hitler lined up in his gun site, but is captured just as he shoots. Beaten & left for dead he escapes back to London, only to be hounded by Nazi spies. Lang always liked spies & its tradecraft & utilizes the clandestine nature & intrigue throughout the story, leaning on bits of expressionistic lighting to add emphasis where needed. The Nazi’s are portrayed as sadistic killers, with little to no regard for anything, but serving the Reich. Joan Bennett co-stars, in the first of her 4 films with Lang, as a cockney prostitute who rescues Pidgeon & adds an element of class differences within British society. The uplifting ending, with Pidgeon taking his life into his own hands, was as much a reflection of wishful thinking at the time of release than a necessary conclusion to the story. For a film that was first offered to John Ford, Man Hunt seems readymade for Lang to emphasize his patriotism to his newly adopted country. #6 Human Desire (1954). During the early to mid-fifties, Lang settled into work at a most unlikely studio with a dictatorial studio chief, Columbia Pictures & Harry Cohn respectively, but was able to churn out several high-quality Noir films, including Human Desire, which starred Gloria Grahame & Glenn Ford. Columbia was cheap & Cohn was a tyrant, but Lang was at a point in his career where he didn’t have many options. Even after 16 years in America & having made the top 5 films on this list, Lang still struggled with finding work within the studio system. Part of it was his acerbic attitude & constant fighting with producers & studio executives, but some of it was Lang’s own inability to adjust to a new reality of filmmaking. In Human Desire, however, Lang attempts to move outside the 4 walls of a studio soundstage by intercutting scenes of Jeff Warren (Ford) driving the train that centers the story & additional shots in & around the train yard. The story itself is pure Noir as Grahame’s character first seduces Jeff to cover up a murder, then attempts to involve him in the murder of her husband. Ford is a decent man caught in the web of Grahame’s femme fatale, but is grounded by an adoptive family, whose daughter pines or him. #5 Ministry of Fear (1944). When I first watched Ministry of Fear I wrote the note “Reality vs. truth vs. Falseness” as a way to describe the root of the twists & turns of Lang’s adaptation of Graham Greene’s famous novel. While often viewed among Lang’s classics, he later said that he did everything to get out of directing it because he thought the script so weak. Complete with seances, spy rings, a protagonist recently released from an insane asylum & Nazis out for murder, the film had just about everything to make it unbelievable, but in Lang’s hands the implausible becomes possible & the extraordinary becomes mundane. Ray Milland stars as the man sentenced to an insane asylum for the mercy killing of his wife, who unwittingly stumbles into a plot to plant a bomb in war torn England. Nobody is who they appear to be & nobody can be trusted, which plays right into Lang’s notion that everyone must wear a mask of some sort to survive. The film is often compared to Hitchcock’s work at the time, because of the film’s more whimsical approach to the material and willingness to gloss over plot details in the service of style, much of which can be credited to the film’s producer, who assembled the finished film. In fact, Lang never liked the film, but in it there is much to be compared to Lang’s other great work, including camera placement (the scene in Duyea’s clothing store), lighting (the scenes at Scotland Yard) & mis en sen (Lang’s constant use of camera movement creates a dizzying effect that augments the crazy story). #4 Clash By Night (1952). Barbara Stanwyck stars as a bad girl who returns home in hope of redemption, but instead marries one man & is corrupted/corrupts another. The immensely talented Robert Ryan co-stars as the bad man out to ruin Stanwyck’s marriage in this classic Noir love triangle. Paul Douglass plays the simpleton husband, blinded by love & loyalty…until he’s not. Aside from some crashing waves and an opening montage of fishing boats, the film is studio bound like many of Lang’s films. Here he uses claustrophobic interiors and a stifling Summer heat wave to force the characters/actors to a heightened emotionality, with just as much snarling as sweet talking amongst the threesome. Stanwyck is her usually spectacular self, but the real revelation is Ryan, who gives his braggadocious lecher a momentarily soul as he bares himself professing his love for Stanwyck. The film is also famous for one of Marilyn Monroe’s early films. #3 The Woman in the Window (1944). This film is the first of back to back films starring Edward G. Robinson, Joan Bennett & Dan Duryea as a doomed love triangle. Robinson plays a mild-mannered professor, comfortable kibitzing with his cronies while his wife & child are away for the Summer. After a night of drinking, as he admires a portrait of a beautiful woman in a shop window, he sees the reflection of the same woman standing next to him. What begins as an odd coincidence quickly leads to murder, a cover-up & blackmail, all leading to one of the darkest finale’s in Lang’s filmography. As scripted by Nunnally Johnson (The Grapes of Wrath, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit), Robinson’s professor Wanley is a doomed character, who unfortunately chose to resolve his problem in a way not suitable to the Production Code, so vigorously enforced in the mid-40’s. Lang sided with studio brass in altering the final scene, making it more palatable to the Code office, but defeating Johnson’s original intentions & opening the film for its harshest criticism. I agree with Johnson, but also realize that without the coda, the film could never have been released. While still soundstage bound, Woman in the Window is filled with brilliant use of chiaroscuro lighting, photographed by the brilliant cinematographer Milton Krasner (An Affair to Remember ‘57, All About Eve ’50)Fortunately, what comes before the coda is classic, dark Fritz Lang & even with the coda, the film was a huge success, which led to the making of the #1 title on this list! #2 The Big Heat (1953). At once Lang’s last great masterpiece & containing his most notorious scene, The Big Heat is down & dirty Film Noir at its best. Glenn Ford is a detective tasked with unraveling the apparent suicide of a corrupt cop, which puts him against the mob, led by the ruthless & sophisticated momma’s boy Mike Lagana. His determination leads to personal tragedy & disillusionment, but it also leads him to Debby, the gangster’s moll, who has ax to grind with her boyfriend Vince (Lee Marvin) & a willingness to help an attractive cop. In one of her best performances, Noir queen Gloria Grahame commands every scene she’s in & her Debby is a combination of ditzy sexuality & steely determination. Grahame would actually be awarded her only Oscar, for best supporting actress for The Bad & the Beautiful (’52), just as The Big Heat started shooting. In a testament to the efficiency of ‘50’s Hollywood, The Big Heat went from a serial in The Saturday Evening Post in December 1953, to first script on January 20th & before the cameras on March 11th, 1954. In the first of 2 famous scenes where hot coffee is thrown in anger, Lang decides to focus not on the victim, but on the twisted face of the perpetrator, further emphasizing the evil at the heart of man. Filming took less than 4 weeks on the 89-minute thrill ride, but the film received only middling reviews & soft box office. In January of 1955, however, French film critic & future director Francois Truffaut lauded the film in a 3-page review, beginning the rehabilitation of the master’s final triumph #1 Scarlett Street (1945). Taking advantage of the red hot reception to The Woman in the Window, Lang formed his own production company, to be distributed by Universal, with Joan Bennett & her husband, producer Walter Wanger, called Diana Productions. Finally, Lang believed himself free from controlling producers who challenged his genius. The film was based on a French novel (La Chienne-The Bitch), that had been previously made into a 1931 film by Jean Renoir. Reuniting Bennett, Robinson & Duryea, from The Woman in the Window, & in essence making a loose remake, Scarlett Street ratcheted up the drama, making the story about a henpecked clerk who is seduced, then destroyed by a manipulative gold digger, Lang’s American masterpiece. There would be no 11th hour reprieve, as there had been in Woman. Instead, there are overtones of impotence, blatant fetishism, forgery, a violent murder, a frame job & insanity! In other words, Scarlett Street is nearly a perfect Film Noir. One odd note about the pre-production had Lang working with Ludwig Bemelmans, the writer of the children’s book series Madeline on the initial drafts of the screenplay, but the author got sick of Lang’s disdain for writers & quit abruptly.

While Robinson is expert in his playing of the milquetoast clerk & Bennett is the epitome of seductive evil, it is Duryea who steals the show as the abusive boyfriend/pimp. His nonchalance belies a hair trigger anger that manifests itself in his violence towards & control of Bennett. She lords her sexuality over him, but his constant demeaning of her & treatment of others showcases Duryea’s ability to make even the most despicable characters somehow likable. In a rare feat of Hollywood capitalizing on a good thing without ruining it, Scarlett Street actually rises above The Woman in the Window, while essentially repeating itself in tone, actors & characterization! If you’ve read this far you understand that this list does not include M (’31), Metropolis (’27) or Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (’22), which are all masterpieces of not just Lang, but in all of cinema. Instead, I have chosen to focus on his American films, his second act, with a particular emphasis on his Films Noir because there is a thread which ties them all together in their darkness & reflections of man’s inhumanity, a belief at the core of Lang’s psyche. He was often called a tyrant, often mistreated those closest to him & made it hard to maintain long friendships, but Lang was a focused genius. If that’s not forgivable, then focus merely on the greatness of his works ignoring the man behind them, for within this list there are at least 2 master pieces & a handful of classics within the Film noir movement, a movement which he definitely helped shape & define. Sources: Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast. Patrick McGilligan. St. Martin’s Press. 1997 Fritz Lang in America. Peter Bogdanovich. Preger Film Library. 1967. Film Noir: The Directors. Ed by Alain Silver & James Ursani. Limelight Editions. 2012 Film Noir: The Dark Side of the Screen. Foster Hirsch. DaCapo Press. 1981 The Big Heat. Colin McArthur. BFI Film Classics. 1992.

1 Comment

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed