|

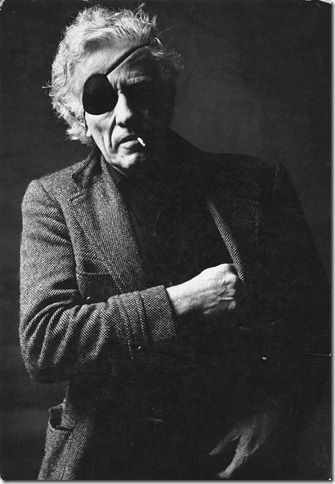

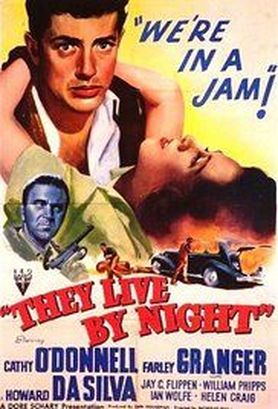

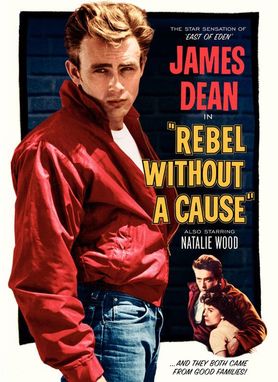

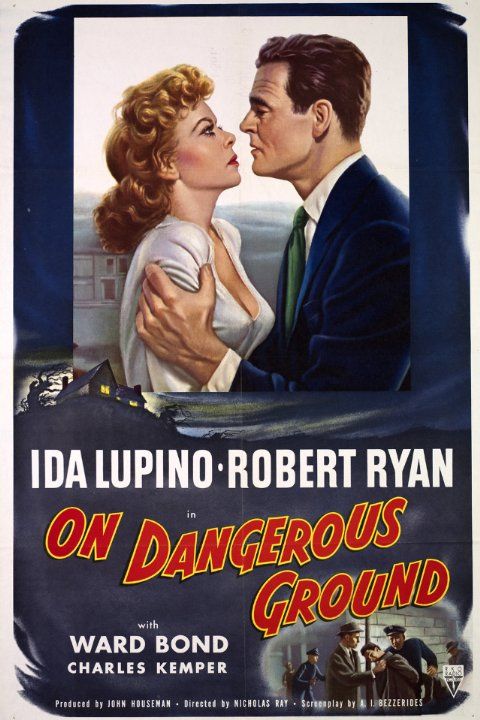

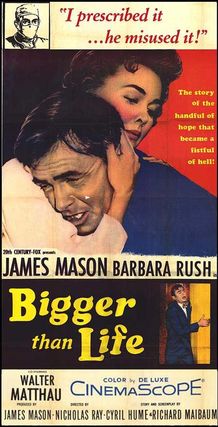

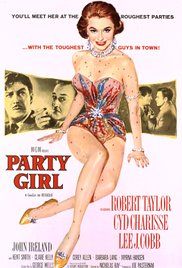

"The cinema is Nicholas Ray."-Jean-Luc Godard The rationale: Nicholas Ray was an interesting man. He was born in LaCrosse, Wisconsin, spent time in the New York theatre world and eventually made it to Hollywood where he directed the seminal teen-age angst film, Rebel Without a Cause & perhaps Bogart's best performance, In a Lonely Place, but to many he is unknown. He was prickly and often acerbic, but he enjoyed working with actors and often coaxed career best performances out of them. He studied architecture under Frank Lloyd Wright, was a member of the Group Theatre in New York & collected folk songs for the WPA throughout the south. Once he did venture to California, as the behest of Elia Kazan (On the Waterfront '54, East of Eden '55, Streetcar Named Desire '51), it was as the assistant director on Kazan's classic A Tree Grows in Brooklyn ('45). Ray often admitted that everything he knew about directing he learned from watching Kazan. What he did create after that brief tutorial was a collection of eclectic and entertaining movies that were often deeply personal and sometimes culturally influential. In a Lonely Place is characteristic of many of Ray's films in that it captures people outside the norm of community as they struggle for human connection, if not love and acceptance. Bogart stars as Dix Steele, a troubled screenwriter on the down side of his career who happens to be accused of murder. Gloria Grahame, in perhaps her best performance as well, plays Steele's love interest & potentially the only one who can save him from prison and from himself. In a Lonely Place is Film Noir to its core as it paints a dark world of a Hollywood that chews people up & spits them out. Sure Dix is a volatile & self destructive person, but is he capable of murder? Everyone doubts him, including his policeman friend and the woman he loves, but they also believe in his basic goodness and that is the tension that drives this film. By the end, Dix's guilt or innocence becomes an afterthought as he tussles with the demons that drive him and the impact they have on everyone he comes in contact with. Emphasizing the eclectic nature of Ray's films is Johnny Guitar, a film often called a psychological western, but with some much more to offer than genre. It's a dreamlike combination of color, quirky settings & both overt & subversive sexual overtones. both gay & straight. It's quite simply unlike any feature film this side of John Waters, but it's brilliant in its subversion of first the western, then sexual roles. The mere fact that both the protagonist and antagonist are women and to a large degree the men are mere window dressing, sets Johnny Guitar apart form most films of the '50's, particularly genre pieces. Mercedes McCambridge, as the villain, spits as much venom as any black hatted snake in a dozen other westerns, but she's also sweet on Dancin' Kid, a local n'er do well & Vienna's boy toy. Vienna is embodied by Joan Crawford and she plays her to the hilt, complete with bright colored clothing, neon red lipstick and a side holster. Ray creates a world unlike any other, with a saloon carved out of the side of a mountain & the crooks hideout accessible only through a waterfall. All that and Sterling Hayden plays the title character, a gunslinger with an angry streak, a guitar slung over his shoulder & a history with Vienna as long as your arm! The climactic shootout takes place in vivid colors and dull blacks and the final outcome is never a sure thing in Ray's topsy turvy wild ride. In many ways They Live By Night is both a precursor and foreshadowing of Rebel Without a Cause, which was released 7 years later. The opening titles of They Live By Night explain that the story is about a boy & a girl who “were never introduced to the world we live in.” Bowie (Farley Granger) & Keechie (Cathy O’Donnell) are 2 young people on the very outskirts of civilization when they meet at Keechies father’s garage; he is an escaped convict & she is kept away from people by her conman father. They form a bond that is at first tentative and awkward, but grows into love as they escape together, on the run from the law and from Bowie’s criminal cohorts. Ray’s first feature was delayed from release for nearly 2 years by the meddling hand of RKO president, Howard Hughes, but was eventually released in a version that Ray approved of. The story of small groups of people, most of the time young, who were outsiders, but bonded to form a pseudo or literal families was to be repeated often in Ray’s work, most notably in Rebel. Whereas Jim, Judy & Plato formed a complete familial unit, Bowie & Keechie are denied that arc with Bowie’s death before their baby is born. The intimate moments as a couple, nesting in the cabin, dining out and snuggling in the front seat of the car are a staple of Ray’s later work, as his protagonists struggle to “be normal” and enjoy simple human pleasures as the world often crushes them from outside. The idea of normal suburban kids leading lives of delinquency, unhappiness and lack of direction was foreign to mid-50’s audiences & Rebel Without a Cause captured all that angst and then some. Led by the dynamic James Dean, who died less than a month before the film’s release, Rebel reflected a part of American youth culture that was not talked about: the disillusion of young people brought about in part by disinterested or overbearing adults and/or peer pressure. Ray’s take on the issue was to portray the teenagers emphathetically, focusing on the yearning for normalcy, however it was individually defined. His fatherly & nurturing relationship with Dean helped cement the performance, along with Sal Mineo’s performance as Plato, as 2 of the richest in movie history. The climactic scene at the iconic Griffith Observatory has all the tension of a great thriller, combined with all the poignancy of great drama, culminating with Jim’s heart wrenching cry at the conclusion. Ray’s use of heightened colors (the film was originally going to be shot in black & white until studio executives saw the initial dailies) & obtuse camera angles & movement helped create a disjointed or hyper-reality that gave the film a dreamlike quality. Remember the scene in Jim’s living room when he confronts his parents. As his mother enters the camera is upside down, captured from Jim’s point of view, and then rolls upright as Jim sits up. Positioning Jim in the camera’s position further deepens the viewer’s identification with the youth in the story. Similarly in the same scene, Ray sets his camera off vertical by about 20 degrees to emphasize the imbalance & confusion in the parental/child relationship. Ray’s identification with and respect for youth culture helped elevate Rebel Without a Cause to iconic status and led the way for a whole new generation of filmmakers to reflect back on what Ray helped create in films like American Graffiti (1973 George Lucas) & Stand By Me (1986, Rob Reiner). When On Dangerous Ground was released in 1952 Ray had directed 5 murder/mystery (later identified as being in the Film Noir cannon) & was on the verge of being type cast as a director of gritty urban dramas. Given the way On Dangerous Ground starts would give a perceptive viewer no reason to think it would be any different, what with the violent cop out to capture a cop killer by any means necessary on the dark & claustrophobic streets of the big city. As the tension builds and the pressure on Detective Jim Wilson (Robert Ryan) becomes too great, the film shifts from the dirty & soul crushing city to the pastoral & wide open vista of a snowy mountain town as Wilson pursues the killer of a local girl. This shift in location is matched by a change in tone that Ray & screenwriter A.I. Bezzerides (Thieves Highway ’49 & Kiss Me Deadly ’55) use to great effect as Wilson transforms into a nuanced & caring seeker of justice, instead of the vengeful tyrant. The snow white landscape if punctuated by mountain peaks and wide valleys, dotted with pine trees, a faw cry from the dirty black streets & foreboding building of the first act. As the hatred and singularity of purpose seeps from Wilson, Ryan’s physical appearance changes, first while he meets and falls for the blind sister (Ida Lupino) of the suspected killer & then as his compassion for the boy grows. When a happy ending was created by Ryan & Lupino & tacked on with Ray’s approval, it put a final stamp on one of Ray’s least downbeat films. While Ray always looked to push boundaries in his filmmaking and in his life, Bigger Than Life may have pushed the furthest and been the most ahead of its time. James Mason is a respected teacher when he is stricken with a life threatening illness that can be put into remission with controlled doses of a new wonder drug, cortisone. When he becomes addicted to the medication it effects his job, his family & finally his sanity. Dealing with issues of drug addiction & mental health in 1956 was a dangerous proposition, especially in a well healed suburban environment. Much like Rebel reflected the youth culture in suburbia, Bigger Than Life looked hard at real problems facing adults in a matter of fact manner. That is was filmed in DeLuxe Color Cinemascope in 1956 only added to the “bigger than life” depiction of real problems, and the reality that Bigger Than Life was a major motion picture that pushed a meaningful social issue. Party Girl has a Pre-Code era setting with a Film Noir plot, complete with a dancer/B-girl with a heart of gold, who is always playing an angle, a corrupt mob lawyer who has a change of heart & a vicious mobster whose drive for self-protection leads to murder. Robert Taylor & Cyd Charisse play the lawyer & dancer respectively and turn in solid performances, but Lee J. Cobb as despicable crook Rico Angelo, complete with chewed cigar constantly in his mouth is all over the top malevolence. Ray continues his contributions to the Noir cannon, this time in color, but always true to the dark soul of a man's heart.

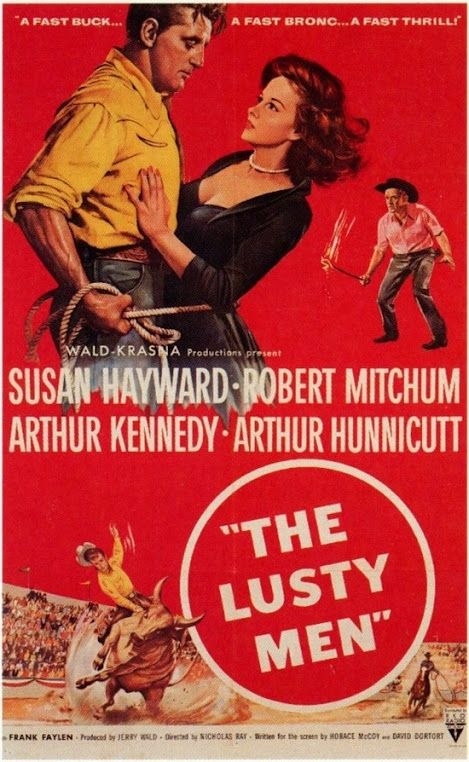

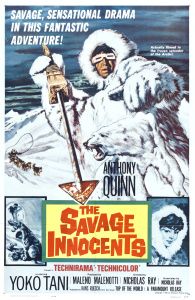

The Lusty Men & Savage Innocents are all about the performances of Robert Mitchum, as an aging rodeo rider in The Lusty Men & Anthony Quinn as a primitive inuit in Savage Innocent. Mitchum is every bit as laconic as he normally is, but his Jeff McCloud has an earthy resolve which separates the performance from others in Mitchum’s canon. In this performance his appeal is not necessary of the animal variety, but born of simple needs. Similarly, Quinn’s Inuk’s only goal is to provide for his family, and Quinn plays those needs not in mere caricature, but in a nuanced fashion that elicits empathy for his plight, not pity. In both cases it is Ray’s nurturing of the performances which helps shape them as unlike others from the actors. As often noted, Ray’s work with actors was fundamental to his directing & these 2 performances bear that out in spades. As complex as any director working primarily in the Hollywood system Nicholas Ray was able to craft personal stories out of the scripts, scenarios & ideas that were assigned to him. His work with actors, both young and old helped mold the stories into often greater than their parts and in some cases elevate them to classic status. All of his films are interesting, but these 10 represent a wide range of emotion, scope and experience and should each be enjoyed for their singular pleasure.

0 Comments

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed