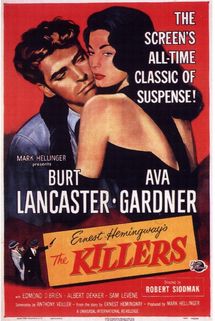

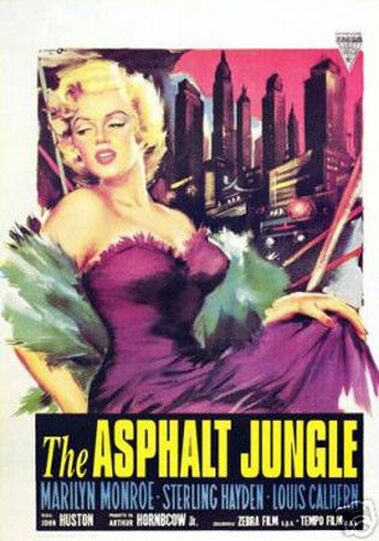

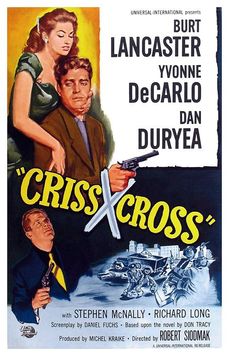

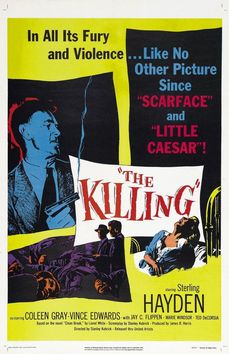

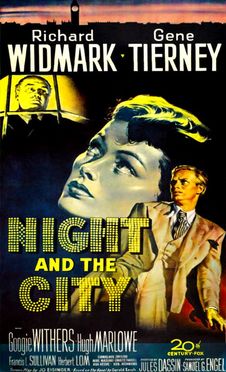

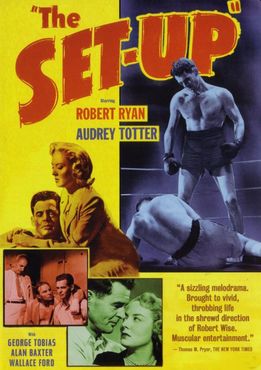

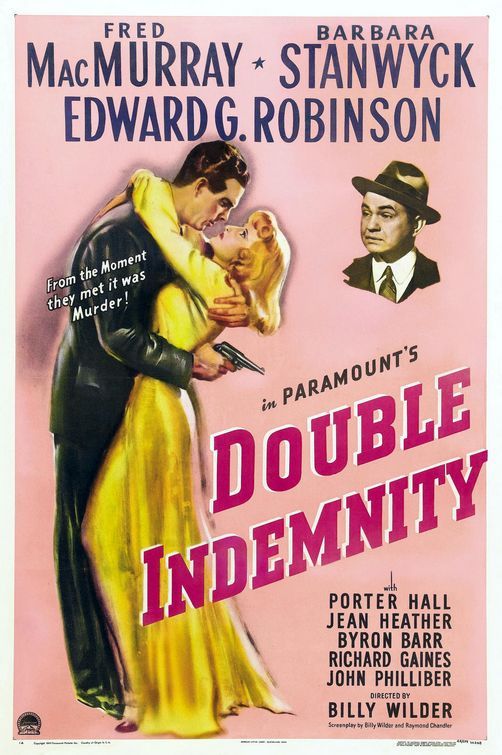

The Rationale: Burt Lancaster stars as Ollie Anderson, known as “the Swede” in Robert Siodmak’s The Killers, my choice for best Film Noir from the classic era. Told primarily in flashback after the hero has been killed, The Killers captures the essence of Noir in a tight 103 minutes. Ava Gardner is Kitty Collins, one of the greatest femme fatales in movie history. She’s as beautiful as she is ruthless, right down to the last scene where she begs for a “death bed” confession to save her skin. Robert Siodmak’s direction & Woody Bredell’s (Phantom Lady ’44, The Unsuspected ’47) moody camerawork combine to offer a primer on Noir atmosphere. From the pools of light that the killers walk into to open the film, to the snappy dialogue in the diner and finally through the myriad of flashbacks, each told from a different perspective by a separate character, The Killers tumbles towards the inevitable conclusion that opened the film; the death of the hero. If there were a king of the heist films it would be The Asphalt Jungle, a ruthless mix of early neo-realism and hardcore Noir. Sterling Hayden is the hooligan Dix Handley, identified by criminal mastermind Dr. Erwin Riedenschneider (Sam Jaffe) as a key cog in his scheme to rob a jewelry store of $1 million in precious stones. Prominent defense attorney Alonzo Emerich (Louis Calhern) is tapped to provided start-up funds & provide the fence for the stolen merchandise, but a sinister double cross does the whole caper in, not before director John Huston draws out the template for all heist films to come however. Alternating between the barren streets of an unnamed American city, the cramped interiors of the underworld & the uptown apartment of Emerich (complete with his delicious mole Marilyn Monroe, in a star turning performance), Huston & co-writer Ben Maddow weave a suspense filled heist picture complete with dirty cops, cheap bookies, safe crackers & gun play. That Dix Headley yearns only to escape the mean streets of the dirty city, consistently shot with overcast skies & empty streets. The cramped interiors, too, offer no room for Headley’s oversized frame to move, it’s as if the walls, floors & ceilings are boxing him into a cage that he longs to escape. All common noir traits, but in The Asphalt Jungle, as in most heist films, escape has but one conclusion & Dix’s escape is well earned. Two more heist films make the list, Criss Cross & The Killing, and both are arguably as good as The Asphalt Jungle. In Criss Cross, as in The Killers, Burt Lancaster is in love with the wrong woman, in this case Yvonne DeCarlo in another film director by Noir auteur Robert Siodmak. As an e-convict armored car driver, Lancaster initiates the heist to cover up a rekindling of an affair with ex-wife Decarlo and to protect her from her current boyfriend Slim Dundee (Dan Duryea). It’s called Criss Cross, but it’s all about the double cross, which of course leads to one the most fated and heart wrenching conclusions in noir. Siodmak & cinematographer Franz Planer’s (Roman Holiday ’53, Champion ’49) use of Los Angeles’ Bunker Hill district adds to their noir palette by utilizing its rolling topography and working class poor makeup to reflect Lancaster’s confused state of mind. DeCarlo has him turning in circles with lust & her unclear motives add to his & the viewer’s uncertainty. The Killing would be a straight up B-movie procedural heist film, but in the hands of director Stanley Kubrick, it becomes not only a classic of the genre, but a template for many of the heist films to follow. Sterling Hayden plays the ex-con ring leader & planner of the racetrack heist that inevitably goes wrong because of the duplicity of a dame, in this case the always great Marie Windsor. What makes The Killing so interesting, however, is that the non-linear storytelling, which was prevalent in Noir, doubles back upon itself, instead of the usual flashbacks used in many Noir films. Pieces of the plot are picked up, moving the plot forward, then dropped, while the story doubles back to another point, slowly rolling out how the heist comes together…and falls apart. If Asphalt Jungle, The Killing & Criss Cross can be grouped as heist films, then Force of Evil, The Set-Up & Night & the City can be grouped together as ‘corruption’ movies because the protagonists each suffer in the face of an overwhelming & menacing entity. In Abraham Polansky’s Force of Evil, the only film he directed before being blacklisted for 17 years through his reluctance to name names during the communist witch hunt, John Garfield plays a corrupt lawyer for the local numbers racket. When he wants to cut his brother in on the action, he must pay a heavy price, in this socially conscious retelling of Cain & Abel. Whereas most Film Noir focused on the small problems of small people, Force of Evil broadens that idea to incriminate & condemn not just the acts of a few people, but society as a whole. The screenplay, also by Polansky, has been compared to blank verse in its lyrical and rhythmic qualities & only adds to the tragedy of the conclusion. Night & the City was also influenced by the House Un-American Activities Committee, as director Jules Dassin was specifically assigned to the London-shot film by producer Daryl F. Zanuck as a means of exiting the U.S. before being named a Communist by fellow director Edward Dmytryk. The fact that the film centers on small-time hustler Harry Fabian (Richard Widmark) as he literally runs for his life throughout, seems reflective of Dassin’s plight and certainly helps imbue Night & the City with an immediacy it might otherwise have lacked. Widmark gives a career defining performance as the rat-like Fabian, scurrying from one ‘hole’ to another, never able to escape the dark & dangerous streets of Soho. In fact, he admits in the final scene that it is only that he is tired of running that has led him to give up, but to the viewer the inevitability of his demise is never in doubt. The Set-Up has Robert Ryan as a washed up boxer looking for one more chance at the big time, but sadly in a fixed fight he’s supposed to lose. The heartbreak & the pathos Ryan emotes as Stoker gives the character dignity even as he first takes a beating in the ring & then in an alley after winning the fight. As he crawls back to his devoted wife, played by the always good Audrey Totter (The Lady in the Lake ’47, Tension ’49), Stoker is physically beaten, but Ryan’s portrayal lifts the character to true heroic heights. Often cited as one of the best boxing movies ever made, The Set-Up takes place in nearly real time over the course of one evening, but packs its 72 minute run time with enough ambiance & unique characterizations that it holds itself up as a classic. Out of the Past & Double Indemnity both take the femme fatale element of the Noir tome as their plot driving force, but use them in far different ways. While Phyllis Dietrichson (Barabra Stanwyck), in Double Indemnity is an overtly sexual & manipulative creature, Kitty Collins (Jane Greer) in Out of the Past is more duplicitous, while still exuding as much sexual energy as the Production Code would allow. Out of the Past ranks as the #3 title on my list because it ticks off every box on the Film Noir template, but does it in such a dynamic way that it could easily (& often has been) my favorite Film Noir. Mitchum is fantastic in my favorite role of his & as noted Greer just drips sexual tension. Director Jacque Tourneur (Cat People ’42, I Walked with a Zombie ’43), director of photography Nicholas Musuraca (The Locket ’46, The Spiral Staircase ’46) & screenwriter Daniel Mainwaring (The Big Steal ’49, Invasion of the Body Snatchers ’56) are perfectly in tune with the dark nature of the storyline and imbue the film with the Noir trademarks of light & dark, tragedy & inevitability. My favorite shot in the movie is when Mitchum finally realizes Kitty’s duplicitous nature, but there’s nothing he can do.

In direct contrast, in Double Indemnity, there is a straight double cross, Phyllis Dietrichson is evil from the get go & her manipulation of Fred Mac Murray’s hapless insurance salesman Walter Neff seems as inevitable as the sun rising. While both films have as their core the turning of a good man bad Billy Wilder’s (Sunset Boulevard ’50, Some Like it Hot ’59) Double Indemnity is a much more overtly sexual manipulation of the protagonist, where Neff’s libido is his sole driving force. What makes Indemnity a classic of the genre is its early establishment of the flashback as a storytelling device & the idea of murder for lust. As in Noirs that came later, like The Postman Always Rings Twice (’46) & much later in Body Heat (’83) & Blood Simple (’91), the killing of a spouse is never as easy as it seems, but Indemnity established the template perfectly! Finally, there is In a Lonely Place and I leave it for last for a reason; it is the single most memorable movie on this list. The plot is not all that complicated & more or less linear, the lighting is not necessarily in the Noir tradition & there is no classic Femme Fatale, but it is a wonderful character study of a tortured soul, brilliantly played by Humphry Bogart, in what I believe is his finest performance. While there is a mystery to unravel, brought about solely by Bogart’s Dixon Steele’s alcoholism and inner demons, it is almost secondary to the greatness of the film. It’s the inner workings of Steele’s mind, his interaction with people & finally his love for a woman, Laurel Gray (Gloria Grahame) that makes this movie unlike any other on the list, certainly Noir, but in a more cerebral way. The darkness is all in Steele’s mind & director Nicholas Ray, who was married to Grahame while the film was being shot, mines the most out of Bogart’s performance by allowing him to emote very little, then explode in rage. The final shot, while tragic in a Noir kind of way, is one of the saddest in all of movie history, but it perfectly captures the essence of In a Lonely Place.

0 Comments

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed