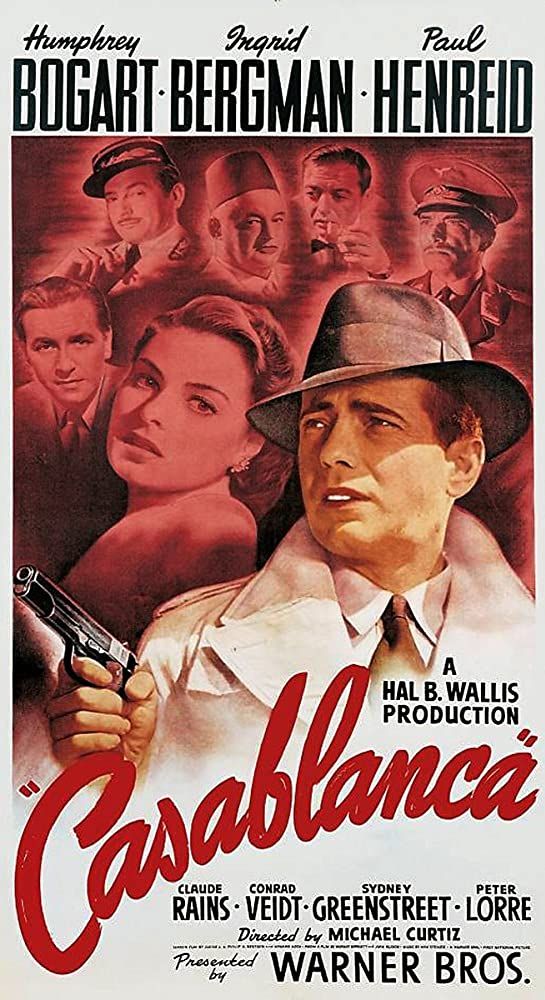

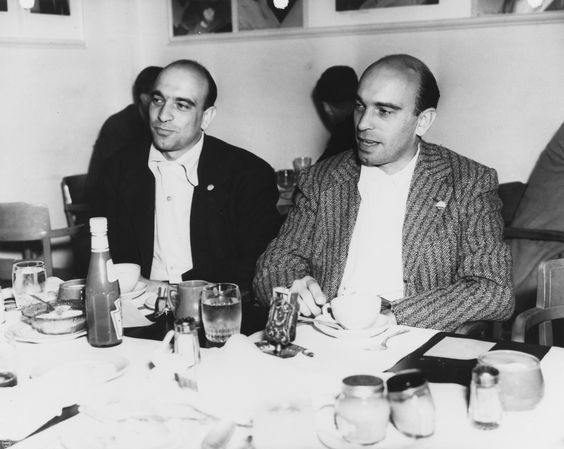

Part I: Bogart before Casablanca & The Source Material Humphrey Bogart, the single entity most associated with Casablanca, had made 43 films, playing mostly heavies and supporting roles, before production on the film began on May 25th, 1942. In fact, the size of Bogart’s roles could generally be summed up by how late in the final reel that his character died, often at the hands of lead actors such as James Cagney or Edward G. Robinson. In his first 35 films, for instance, he was killed in 18 of them and generally unsympathetic in 29. It wasn’t until The Maltese Falcon, released the year before Casablanca, that Bogart rose to star caliber roles. Even as Warner Bros. was acquiring the source material that Casablanca is based on, executives were commenting that the role of Blaine would be perfectly suited to George Raft, Cagney…or Bogart, a meteoric rise for a workmanlike actor, with little heretofore romantic leading man experience. Rick Blaine was to be the role that created “Bogie” the icon, cementing his oft repeated tough ‘on the outside’ loner, with a soft and romantic core that combined to create a moral code that attached audiences to his every film for the rest of his career. Before Bogart was Blaine, even before Casablanca was called Casablanca, there was an un-produced play, written by a high school history teacher and his writing partner, called “Everybody Comes to Rick’s.” Murray Bennet and Joan Allison had shopped the script around New York with no luck, so they began soliciting it to the Hollywood studios. A story reader at Warner Bros. turned the story of a lawyer from Paris who abandons his wife and child and ends up in French Morocco, into a 22-page synopsis that also including the unpromising notations: “the story needs work, but has an interesting set up,” while calling it “sophisticated hockum.” (Lebo, p. 37), and finally noting it might be “…perfect for Bogart, Cagney or Raft and Mary Astor.” Executives, including producer Jerry Wald saw the potential as an extension of Warner Bros. tough guy films, while eventual Casablanca producer Hal B. Wallis sold it to studio chief Jack Warner as reminiscent of Algiers, a very popular film from 1938 that starred Charles Boyer and Hedy Lamarr. Describing Rick as “2 parts Hemingway, 1 part Fitzgerald and a dash of café Christ” (Lebo, p. 42) Wallis sold the studio chief and Warner agreed to purchase the play for $20,000, the highest amount the studio had paid for an un-produced play in its history. In a strange twist of fate, the deal was agreed to within hours of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Only weeks later, on New Year’s Eve 1941, Wallis would change the title from “Everybody Comes to Rick’s” to Casablanca and the rest, they say is history. Part 2: Creating the Screenplay & Building the Perfect Cast Making a movie out of a play, even a popular and well-regarded play, is no simple task. Turning Everybody Comes to Rick into Casablanca would take 3 primary screenwriters, an additional part time writer and countless staff writers at Warner Bros. more than a year to transition the basic story into a shooting script as concise and thoughtful as what ended up on the screen. Brothers Julius and Philip Epstein created the general organizational structure of the film, including many of the lighter comedic parts and several of the most memorable lines. Howard Koch focused on many of the key plot points and character development, while Casey Robinson, working part time and uncredited, labored over the Victor Lazlo character and the 2 romantic scenes between Rick and Ilsa. As was the studio practice at the time, the writers worked independent of one another (except the Epsteins), with the producer, Hal B. Wallis, working to integrate the pieces and refine different elements into a whole. Along the way, the female lead was changed from an American named Lois Meredith to a European named Ilsa Lund, the final scene moved from Rick’s Café to the airport and Rick’s past was deliberately made more vague, eliminating the wife and kids altogether. Perhaps the two most troubling elements of the script also took the longest to resolve; the character of police prefect Renault and the final scene that was moved to the airport. In the case of Renault, it was the censors at the Production Code office who took the filmmakers to task over the police officer’s moral character. The play overtly expressed that Renault traded sex for visas, making it both verbally and physically evident that he was a lecherous and corrupt individual. In fact, a scene between Renault and the German major Strasser was cut from a working script because it exposed Renault’s predatory nature. While the implication of such impropriety certainly exists in the film, it is tamped down and never physically manifested either on screen or directly implied off screen. Also, Renault’s repeated failure at being able to ply his trade is a source of amusement for Rick and frustration for Renault, which helped offset the underlying implications for the censors. Renault’s position as a representative of the Vichy government, however, also created issues for the censors, worried about offending any part of the viewing public, including those in Northern Africa. For this reason, his capitulation to the German’s was offset by his understated disdain for their practices and leads to his reversal of attitude in the last scene. Most of the issues with Renault’s character were solved before production began, which was definitely not the case for the other major difficulty within the script, the final scene. While it is an oft repeated fallacy that the ending of whether Ilsa would leave with Lazlo or stay with Rick was in flux throughout production, it simply isn’t true. Scriptwriters, the producer, Wallis, Michael Curtiz and studio executives all agreed early on that Ilsa must leave with her husband, for a variety of reasons, but the conundrum became how to make that eventuality pleasant for a viewing public hooked on the Ilsa/Rick love affair. There was also the problem of Renault’s presence in the final scene as a deterrent factoring into the logistics of getting Ilsa on the plane. During production, however, there were scripting breakthroughs that would finally lead to a resolution. The catalyst was uncredited script writer Casey Robinson adding the second nighttime scene between Rick & Ilsa where she asks him to think for the both of them. Clearly the trigger for the final scene, but still not a logical link to the resolution. Earlier, the final scene had been changed from occurring in Rick’s Café to the airport, which allowed for a staggered arrival of the primary character, most notably major Strasser. The studio elicited the help of perhaps 75 staff writers to solve the problem, but it wasn’t until the night before shooting that a finalized version of the final scene was shared with cast and crew, most likely created in a weekly script brainstorming session Wallis held at his house. The famous “hills of beans” speech, “we’ll always have Paris” & the final “here’s looking at you, kid” all came together to create perhaps the greatest manifestation of love ever captured on screen. There were problems remaining, however, most notably how to dispose of Strasser and plausibly eliminate Rick & Renault from German prison camps, while putting a final stamp on the film. The first issue provided an immediate conflict between director and star, as the script as written had Rick shooting Strasser in the back; an option that left Bogart apoplectic. A compromise was reached after half a day of deliberation and grandstanding and Rick was able to shot Strasser face to face in a dignified manner. Finally, the last and perhaps most famous line, “Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship”, was dubbed in weeks after shooting ended. Wallis was unsatisfied with the closing line so he added the capstone of what of the greatest screenplays ever written. If the screenplay for Casablanca can be held up as one of the most concise and well-constructed in film history, then the casting of the film surely stands beside it as a reflection on near perfections as well. As with the screenplay, however, there was no straight line or master plan at work in the cast’s construction, rather it was pieced together with good intentions, shrewd awareness of the task at hand and even a bit of horse trading, all mindful of a rather restrictive budget. While initial story readers identified the script as perfect for Bogart, Warner Bros. used an initial press release to pump up 2 stars that were never really considered for Casablanca, which led to one of the greatest misnomers about the film. In January of 1942, well before formal casting was begun Warner Bros. released word that Ronald Reagan and Ann Sheridan were being cast in Casablanca. Neither was seriously considered for the film, but WB didn’t want to miss an opportunity to promote Kings Row, which was releasing in February, starring the 2 actors. Reagan’s association with Casablanca has been passed down ever since, but as with most of what came from studio publicity departments, it was pure fantasy. George Raft, on the other hand, campaigned for the role of Rick, after having turned down several earlier roles, including High Sierra and The Maltese Falcon that helped launch Bogart’s career. Raft’s memo pleading with Wallis for the part was answered quite succinctly by Wallis with “the part is Bogart’s.” Casting the part of Ilsa was not as straight forward, with several actors, including Hedy Lamar considered for the role (she wasn’t available). David O. Selznick, the producer of Gone With the Wind and Rebecca had a personal contract with Ingrid Bergman and was initially reluctant to loan her to Warner Bros. for the part. Wallis finally sent the Epstein’s to Selznick’s office to tell the story of Casablanca and convince the producer. As they tell it, Selznick spent 20 minutes shuffling pages while they energetically told the story, not pausing, until they mentioned the film was ultimately very similar to Algiers, which was enough to convince him to loan her for the role. Bergman herself had a bit of trepidation in accepting the loan out because she was already slated to star in Paramount’s production of For Whom the Bell Tolls and didn’t want to lose a part she would go on to be Oscar nominated for, due to production delays on a film she considered less import. She was signed to Casablanca just 2 weeks before production began. role. Paul Henreid was initially ruled out because he was busy shooting Now, Voyager (1942) and it was assumed he wouldn’t be available. Joseph Cotton desperately wanted the role, but was also busy at the time of production. Finally, Wallis settled on juggling the shooting schedule to have Henreid play the role, even if it meant he wouldn’t show up on set until a month into shooting. Similarly, the part of major Strasser vacillated between veteran actors, including actor/director Otto Preminger for the part, but his salary demands of $7,500 per week were too expensive. Conrad Veidt, a famous German actor since the early 1920’s (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), an outspoken anti-Nazi, was offered the part and ended up being the highest paid actor in the cast. His appealingly malevolent performance as Strasser is one of the highlights in the film. While the Production Code concerned itself with the depiction of several of the characters, simple racist economics and social taboos crafted what became one of the most iconic performances in the film, the character of Sam. Dooley Wilson, a drummer by trade, finally was given the role, but even after Wallis was interested in having his distinctive singing voice dubbed. That Sam is Rick’s only friend and played an equal part in his life, even as he refers to Rick as ‘boss’, created issues with producers worried about box office in the south. Curtiz at one point suggested a black female singer to play the part, but that was quickly dismissed because the mere suggestion of a relationship was too much to consider. Ultimately, we are left with Dooley’s signature raspy vocals on several songs, but none more famous than “As time Goes By,” simply the most famous song melody in Hollywood history. Finally, there were the richly textured characterizations performed by the myriad supporting players, led by Peter Lorre, as Ugarte, and Sydney Greenstreet as Ferrari. Neither actor was on screen very long, but their performances impact the film in far greater ways. For Lorre, his 4 minutes of screen time, noted as more of a “catalyst than a character” oozes with a self-deprecating smarm and disarming danger, even as he coolly jokes with Rick. In many ways, Ugarte personifies the desperation of Casablanca, the place, and Lorre is the main reason why. Greenstreet’s Ferrari similarly creates an aura around his character that far outweighs his screen time, and quickly shapes the perception of the man. Among the other supporting characters included more than 40 actual European refugees, including several from director Curtiz’s native Hungary, like S. Z. Sakall (Carl) and French star Marcel Dalio (The Grand illusion ‘37, The Rules of the Game ’39). The singing of La Marseillaise, for instance, was not mere performance for many of the actors and their personal feelings can be seen in the several closeups during the scene.

0 Comments

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

- Anatomy of a Murder Notes

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed