Godard Top 10 (1960-1967)

|

1. Pierrot Le Fou (1965)

2. Contempt (1963) 3. My Life to Live (1962) 4. Band of Outsiders (1964) 5. Breathless (1960) 6. A Woman is a Woman (1961) 7. Alphaville (1965) 8. Masculine Feminine (1966) 9. 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her (1967) 10. Weekend (1967) Godard and Anna Karina: The Inflection Point

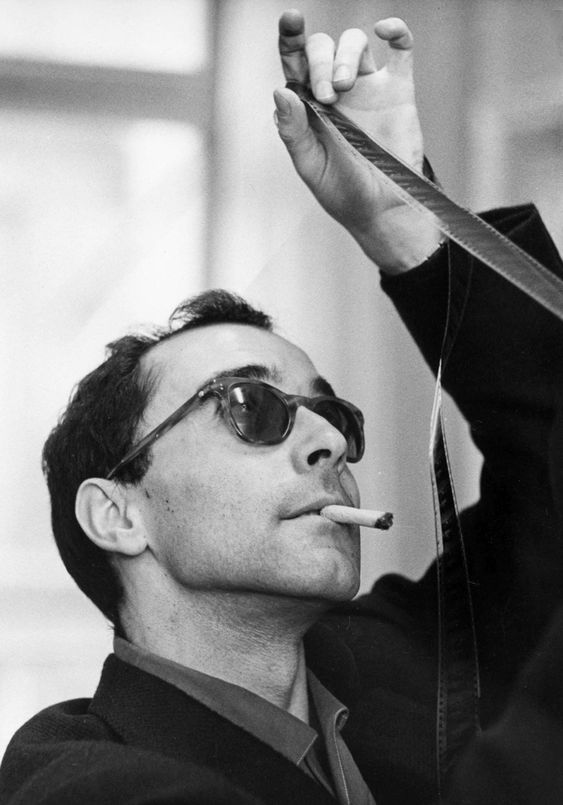

Jean-Luc Godard is definitely to be included in any French film ‘Mount Rushmore.” His impact on world cinema over the course of 50+ year career is unquestioned. For many people, however, there is a delineation within his filmography around the year 1967. Godard felt that film was life and vice versa, and for certain periods his films spiraled in on themselves as Godard worked out an idea, an ideal, a subtle or obvious point or attempted to push the medium beyond anyone else’s understanding or capabilities. By 1967, he had made, among other films, Breathless (’60), A Woman is a Woman (’61), My Life to Live (’62), Contempt (’63), Alphaville (’65), Pierrot Le Fou (’65) and Band of Outsiders (’64); each a classic and influential film, as well as among his most popular and famous films. For Godard, 1967 was an inflection point because his life was changing and his interests no longer aligned with popular film culture or techniques. For life and for cinema there had to be a change. |

Perhaps it was the end note on his film Weekend (’67), noting ‘end of story’ ‘end of cinema,’ that put on film what Godard was feeling. His political beliefs kept him making films, but he was largely uninterested in participating in the commercial pursuit of film. Before then, however, his output forever changed the landscape and understanding for what cinema could and should be. He influenced generations of filmmakers from all over the world, including Jim Jarmusch, Wong Kar-Wai, Christopher Nolan and Quentin Tarantino. His films in the early to mid-sixties were accessible and filled with pop references and “meta” allusions to other films. More importantly, they were alive with energy, radiating an effervesce, even as the characters faced poverty, the police and death, that was unparallel among his contemporaries, his predecessors or his disciples.

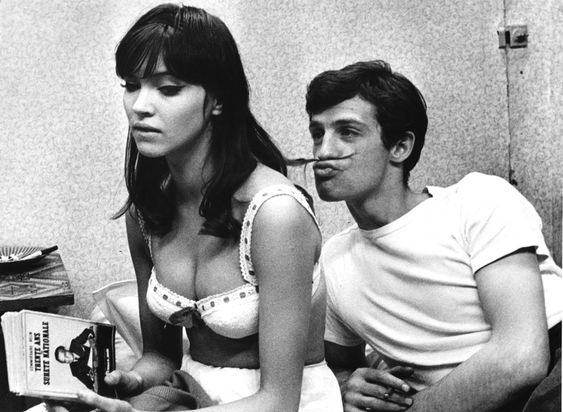

Could it have been the impact of the end of his collaboration with actress Anna Karina that so profoundly changed Godard? To call her his muse simplifies his attitude towards film. Cinema was his muse, but there is no doubt that Karina influenced not only the 7 films they made together from 1961-1966, but several of his other films during that period. She could be argued as the sole distraction that Godard had from the pure belief in cinema as life. The couple’s relationship weighed heavily upon each of Godard’s films, from the utter adoration his camera captured in A Woman is a Woman (’61), through the dissolution of their marriage in 1965, reflected in Peirrot Le Fou to the end of their collaboration in Made in the U.S.A (’66). Even in films, like Contempt (’63), where Karina doesn’t even appear, her presence is palpable in the creation and performance of the female lead. That that personae could leak into a character played by Bridget Bardot is truly amazing given the strength of her presence and performance, but such was the interconnected nature of Karina and Godard.

Could it have been the impact of the end of his collaboration with actress Anna Karina that so profoundly changed Godard? To call her his muse simplifies his attitude towards film. Cinema was his muse, but there is no doubt that Karina influenced not only the 7 films they made together from 1961-1966, but several of his other films during that period. She could be argued as the sole distraction that Godard had from the pure belief in cinema as life. The couple’s relationship weighed heavily upon each of Godard’s films, from the utter adoration his camera captured in A Woman is a Woman (’61), through the dissolution of their marriage in 1965, reflected in Peirrot Le Fou to the end of their collaboration in Made in the U.S.A (’66). Even in films, like Contempt (’63), where Karina doesn’t even appear, her presence is palpable in the creation and performance of the female lead. That that personae could leak into a character played by Bridget Bardot is truly amazing given the strength of her presence and performance, but such was the interconnected nature of Karina and Godard.

While neither was able to recapture the co-dependent greatness of their collaboration, it cannot be understated that its strength lies in the sum of its parts. Watching the films it clear the arc is often painful and joyless, yet also moving and emotional, sometimes in the same film, and casts an emotional center to Godard’s films in this period. Years after their life together ended Karina repeatedly called Godard the love of her life. Not surprisingly, Godard’s comment was more pointed, but less direct, when he said “the cinema does not quarry the beauty of a woman, it only doubts her heart, records her perfidy, and only sees her movements.” Perhaps their love and collaboration was unbalanced, but these comments spoke to nothing more than a difference in perspective; Karina’s based in reality/life and Godard’s, not surprisingly, remembered through the lens of a camera.