The Man with No Name Trilogy: Sergio Leone's West

|

A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

For a Few Dollars More (1965) The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968) Directed by: Sergio Leone Starring: Clint Eastwood, Lee Van Cleef, Eli Wallach, Gian Maria Volonte Story by: Sergio Leone Music: Ennio Morricone Of all the genres, sub-genres and movements in American Film history, from Screwball Comedies to Film Noir, Musicals to Heist films, none is more purely American than the Western. It’s long and rich history, dating back to origins of narrative film itself (Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery, 1903), speaks to its importance in helping create the American artform, as well as interpreting and exporting the very idea of Americanism. Historians have noted that as many of 40% of films made before 1960 were Westerns, most complete with the trademark conventions of the hero in a white hat, the bad guy dressed in black, whiskey drunk straight, from a shot glass, and the fastest draw always wins, among so many more. John Ford described himself by saying “I make Westerns,” but directors as diverse as Howard Hawks, Anthony Mann and John Sturges all helped add to the mythology and pathos of the American Western. With all those films being created, however, there came a point where enough was enough, at least where the big screen was concerned.

|

By the early 1960’s, moviegoing audiences were tired of the cliched Westerns, featuring aging superstars like john Wayne and Gary Cooper. They were instead comfortable watching smaller Western heroes on their television sets, in the comfort of their living rooms on shows like Gunsmoke, Bonanza and The Big Valley, among others. The Movie Western was in its death throws and fading quickly. Not unlike Film Noir, which had waned in the US, but was being reinvented by European directors like Jean-Pierre Melville and Jean-Luc Godard, the Western moved to Europe and saw not just a resurgence in popularity, but a revitalization in style and tone. As with the French directors of the New Wave, Italian directors had been weaned on American films after WWII and began taking the Western and twisting its core motifs, ideals and visual imagery to reinvent and reinvigorate the core American filmic statement. At first the films were successful locally in Europe, but one director changed that by taking a minor star from a television western (Rawhide) and creating an iconic character in what has been called an “opera of violence.”

Italian born Sergio Leone was born into movies, having a director father and an actress mother. His mother, in fact, appeared in what many believe to be the first Italian western. He initially studied the law, but quickly became immersed in movies, first assisting Italian directors, then moving to work on American films filing in Rome for tax reasons like Quo Vadis, Helen of Troy, The Nun’s Story and Ben Hur. While his positions on the early films were minor, he eventually became the highest paid assistant in Italy. Many credit Leone’s later style as having been developed while working on American films, but he downplayed that, pointing out the rigid style of American directors and crews. What Leone did take from several of the master American directors was the importance of the image, whether small or immense and to focus on the minute details within the frame.

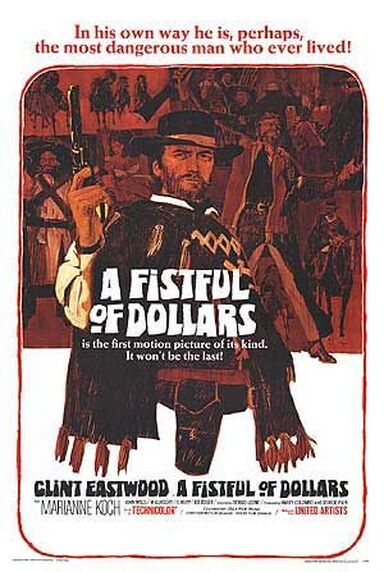

A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

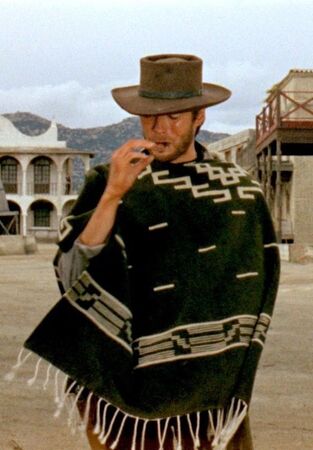

Leone’s second film as a director was A Fistful of Dollars (’64), although he was credited as Bob Robertson to fool Italian movie goers into thinking it was a Hollywood production. Fistful was made on a small $200,000 budget and was based on an Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (’61), a fact that delayed US release of the film until 1967 due to legal issues with Kurosawa’s studio. The story of a lone gunman who pits rival gangs against each other to save a small town, Fistful was an enormous hit across Europe and is largely credited with not only creating the Clint Eastwood movie personae, but embodying the first post-modern Western. Together Leone and Eastwood fashioned the character out of whole cloth, with the director using his limited English to instruct Eastwood to “watch me” while he pantomimed what he wanted. For his part, Eastwood brought his gun, holster and hat from his TV show, the jeans that became his staple and urged Leone to remove dialogue, honing it to the essence of necessity. Finally, Eastwood’s poncho was purchased by Leone in Spain to add the finishing touches on what became known as The Man with No Name.

The film was shot in the Spanish desert by a multi-lingual cast and crew, without sound and with each actor speaking his native language, then dubbed in post-production. In many ways, this silent shooting allowed Leone to create his template after shooting, layering on rich sound effects and Ennio Morricone’s original and magnificent score, but more on that later. Free from the distraction of native sound allowed Leone to take his time building up tension and suspense, then releasing a thunderous burst of violence. Often seeming more violent than they actually are, the films broke new ground in showing a killer pulling the trigger in the same shot as the victim (not allowed under the US Production Code), allowing blood to ooze from bullet wounds and fists to violently break skin in fistfights. The film is certainly not for the faint of heart, but in the between times opposite the violence there is a poetry of faces and enough panoramic vistas to challenge Ansel Adams.

Leone’s second film as a director was A Fistful of Dollars (’64), although he was credited as Bob Robertson to fool Italian movie goers into thinking it was a Hollywood production. Fistful was made on a small $200,000 budget and was based on an Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (’61), a fact that delayed US release of the film until 1967 due to legal issues with Kurosawa’s studio. The story of a lone gunman who pits rival gangs against each other to save a small town, Fistful was an enormous hit across Europe and is largely credited with not only creating the Clint Eastwood movie personae, but embodying the first post-modern Western. Together Leone and Eastwood fashioned the character out of whole cloth, with the director using his limited English to instruct Eastwood to “watch me” while he pantomimed what he wanted. For his part, Eastwood brought his gun, holster and hat from his TV show, the jeans that became his staple and urged Leone to remove dialogue, honing it to the essence of necessity. Finally, Eastwood’s poncho was purchased by Leone in Spain to add the finishing touches on what became known as The Man with No Name.

The film was shot in the Spanish desert by a multi-lingual cast and crew, without sound and with each actor speaking his native language, then dubbed in post-production. In many ways, this silent shooting allowed Leone to create his template after shooting, layering on rich sound effects and Ennio Morricone’s original and magnificent score, but more on that later. Free from the distraction of native sound allowed Leone to take his time building up tension and suspense, then releasing a thunderous burst of violence. Often seeming more violent than they actually are, the films broke new ground in showing a killer pulling the trigger in the same shot as the victim (not allowed under the US Production Code), allowing blood to ooze from bullet wounds and fists to violently break skin in fistfights. The film is certainly not for the faint of heart, but in the between times opposite the violence there is a poetry of faces and enough panoramic vistas to challenge Ansel Adams.

Where Leone broke down the generic codes of the American Western was mainly in character and story. The man with no name, for instance, the ‘hero’ of the film, is morally ambivalent, essentially out for himself, even as he saves the town from the gangs. His silence mutes any potential heroism under a cloud of uncertainty. Simply put, he doesn’t’ telegraph his motives, so the veiweris left to wonder whether he’s acting purely in self-interest or benevolently. Eastwood is pitch perfect as the knowing and stoic loner. Christopher Frayling, Leone’s biographer and an expert on Italian Westerns, noted that Leone helped spin the traditional American convention that “the hero was always the best shot”, to what became the backbone of the “Spaghetti Western,” that “the best shot is always the hero.”

Leone, borrowing liberally from Yojimbo, creates a triangulation of conflict in the 2 gangs and the man with no name, twisting the traditional good versus evil story by engineering the conflict as a moneymaking enterprise. Eastwood’s character becomes the trickster as he dupes both sides into killing each other through a series of misunderstandings that cause chaos and confusion. When he speaks it is often wise cracks that spur on the combatants to more violence. Eastwood’s wisecracking trickster would become the template for future action stars like Bruce Willis, Mel Gibson, and Sylvester Stallone and Leone’s take on traditional Western storytelling and mythmaking would influence a generation of filmmakers. Utilizing flashbacks and dreamlike imagery Leone further distanced himself from Hollywood traditions, even as he commented on and paid homage to greats like John Ford and Howard Hawks, but more on that later!

Little was expected of A Fistful of Dollars, but it was an immediate hit in Italy and other parts of Europe, even becoming the highest grossing Italian film up to that point. The Italian film industry for a long time had ridden waves of similar films in 4 to 5-year cycles, then slumped as the cycle exhausted itself. Such was the case when Fistful opened, as the sword and sandal muscleman epics had run out of steam. Fistful launched the next wave, disparagingly dubbed Spaghetti Westerns by international critics, and Leone didn’t wait long before creating his next masterpiece in what would become the first note of a 4 film symphony.

Because Eastwood was forbidden from making films in the US by his Rawhide contract, Fistful of Dollars made perfect sense, even with a meager $15,000 payday. Although the film wouldn’t be released in the US for nearly 4 years, due to the aforementioned legal action in Japan, its success brought about a quick opportunity to reteam Leone, Eastwood and Fistful baddie Lee Van Cleef for something of a sequel called For a Few Dollars More, made in 196

Leone, borrowing liberally from Yojimbo, creates a triangulation of conflict in the 2 gangs and the man with no name, twisting the traditional good versus evil story by engineering the conflict as a moneymaking enterprise. Eastwood’s character becomes the trickster as he dupes both sides into killing each other through a series of misunderstandings that cause chaos and confusion. When he speaks it is often wise cracks that spur on the combatants to more violence. Eastwood’s wisecracking trickster would become the template for future action stars like Bruce Willis, Mel Gibson, and Sylvester Stallone and Leone’s take on traditional Western storytelling and mythmaking would influence a generation of filmmakers. Utilizing flashbacks and dreamlike imagery Leone further distanced himself from Hollywood traditions, even as he commented on and paid homage to greats like John Ford and Howard Hawks, but more on that later!

Little was expected of A Fistful of Dollars, but it was an immediate hit in Italy and other parts of Europe, even becoming the highest grossing Italian film up to that point. The Italian film industry for a long time had ridden waves of similar films in 4 to 5-year cycles, then slumped as the cycle exhausted itself. Such was the case when Fistful opened, as the sword and sandal muscleman epics had run out of steam. Fistful launched the next wave, disparagingly dubbed Spaghetti Westerns by international critics, and Leone didn’t wait long before creating his next masterpiece in what would become the first note of a 4 film symphony.

Because Eastwood was forbidden from making films in the US by his Rawhide contract, Fistful of Dollars made perfect sense, even with a meager $15,000 payday. Although the film wouldn’t be released in the US for nearly 4 years, due to the aforementioned legal action in Japan, its success brought about a quick opportunity to reteam Leone, Eastwood and Fistful baddie Lee Van Cleef for something of a sequel called For a Few Dollars More, made in 196

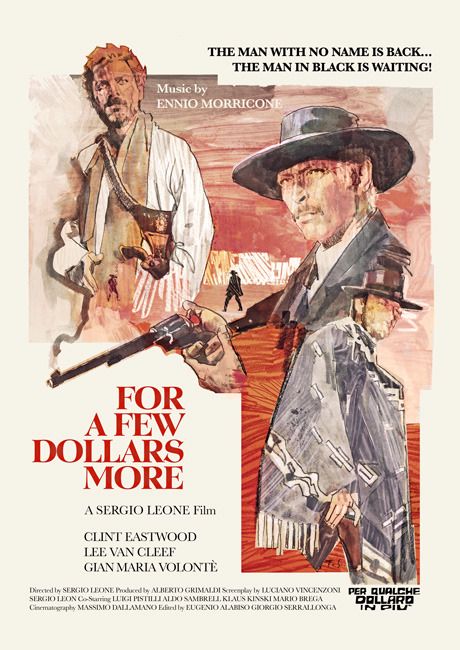

For a Few Dollars More (1965)

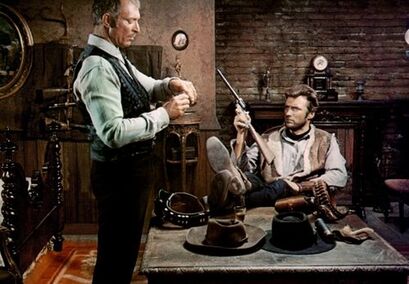

Eastwood reprises his Fistful man with no name character, but this time both he and VanCleef, playing a Civil War veteran, are bounty hunters out to capture El Indio, a ruthless bank robber and gang leader. As first advisories, the two form a competitive partnership that ebbs and flows throughout the film. Some have read a gay subtext into the relationship through Leone’s interesting camera placements and subtle dialogue cues, but for me the relationship is more akin to a classic father/son dynamic like John Wayne and Montgomery Clift in Hawks’ Red River (’48). The richness of the familiar relationship between the men was noted by Leone as a surrogate for his loneliness as an only child, but the relationship can be looked at as a template for buddy action/comedies for future films.

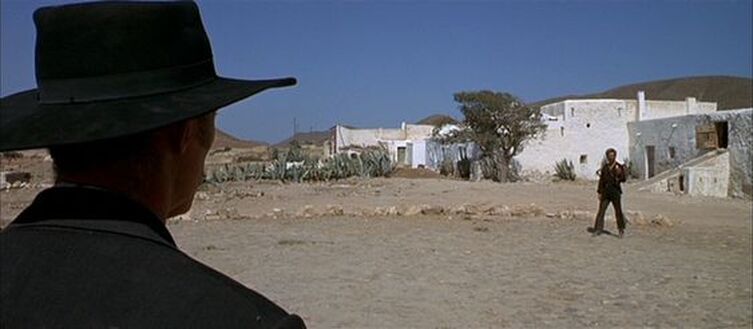

Leone really dials in his signature visual style with For a Few Dollars More, emphasizing his use of ‘big heads’, that is a foreground close up of a man’s head or face, with background action or characters, creating immense three dimensionality and depth of image, as well as skewed perspective. Leone also went one step further in utilizing extreme close ups to allow tension to build, intercutting between characters and props, like guns, to enhance the expectation of violent explosions. By combining extremes in image creation, including incredibly panoramic long shots, capturing as much topography of the Spanish desert as possible, Leone could manipulate the viewer emotionally, forcing their gaze to search for meaning within the frame, all without using dialogue. Once again shooting without sound, as was the Italian practice, Leone built his frames first with image, then layered on sound and music to further draw in the viewer, adding meaning to the wordless pictures. Even while he continued to manipulate character and story, Leone built upon A Fistful of Dollars with more dynamic and rich imagery, bringing a new immediacy to his deliberately paced cat and mouse game between the bounty hunters and the outlaws.

Eastwood reprises his Fistful man with no name character, but this time both he and VanCleef, playing a Civil War veteran, are bounty hunters out to capture El Indio, a ruthless bank robber and gang leader. As first advisories, the two form a competitive partnership that ebbs and flows throughout the film. Some have read a gay subtext into the relationship through Leone’s interesting camera placements and subtle dialogue cues, but for me the relationship is more akin to a classic father/son dynamic like John Wayne and Montgomery Clift in Hawks’ Red River (’48). The richness of the familiar relationship between the men was noted by Leone as a surrogate for his loneliness as an only child, but the relationship can be looked at as a template for buddy action/comedies for future films.

Leone really dials in his signature visual style with For a Few Dollars More, emphasizing his use of ‘big heads’, that is a foreground close up of a man’s head or face, with background action or characters, creating immense three dimensionality and depth of image, as well as skewed perspective. Leone also went one step further in utilizing extreme close ups to allow tension to build, intercutting between characters and props, like guns, to enhance the expectation of violent explosions. By combining extremes in image creation, including incredibly panoramic long shots, capturing as much topography of the Spanish desert as possible, Leone could manipulate the viewer emotionally, forcing their gaze to search for meaning within the frame, all without using dialogue. Once again shooting without sound, as was the Italian practice, Leone built his frames first with image, then layered on sound and music to further draw in the viewer, adding meaning to the wordless pictures. Even while he continued to manipulate character and story, Leone built upon A Fistful of Dollars with more dynamic and rich imagery, bringing a new immediacy to his deliberately paced cat and mouse game between the bounty hunters and the outlaws.

With his maturing visual style, Leone also took the time to enrich and subvert traditional characters, most notably bad guy El Indio, played by Italian stage actor Gian Maria Volonte. In a performance that would in some ways foreshadow Eli Wallach’s Tuco in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly the following year, Volonte performs in stark contrast to Eastwood’s stoic and silent man with no name, talking when he should be quiet and boisterously bragging and threatening. Where El Indio differs from Tuco, however, in in his sadistic tendencies, his blatant drug use and his complete lack of moralality, loyalty or conscience. He’s not only Ugly, he’s evil, but he also talks too much, just like Tuco.

Further adding to the maturing storytelling is the inclusion of dreamlike flashbacks and the incremental exposition of certain characters, creating additional layers to the film. Both El Indio and Van Cleef’s Colonel Mortimer remember a shared experience in different ways and Leone only exposes the personal impact in the final reel, shattering allusions and exposing the true nature of grief and the viewer’s perceptions. In allowing Mortimer to evolve, Leone again plays on the traditional Western convention that only the hero can evolve, leaving Eastwood’s character to not only collect the dead bodies for his bounty, but to stop and grab the cash as well. He remains static and unknown, yet centers the film, unlike any traditional hero in American Westerns.

Further adding to the maturing storytelling is the inclusion of dreamlike flashbacks and the incremental exposition of certain characters, creating additional layers to the film. Both El Indio and Van Cleef’s Colonel Mortimer remember a shared experience in different ways and Leone only exposes the personal impact in the final reel, shattering allusions and exposing the true nature of grief and the viewer’s perceptions. In allowing Mortimer to evolve, Leone again plays on the traditional Western convention that only the hero can evolve, leaving Eastwood’s character to not only collect the dead bodies for his bounty, but to stop and grab the cash as well. He remains static and unknown, yet centers the film, unlike any traditional hero in American Westerns.

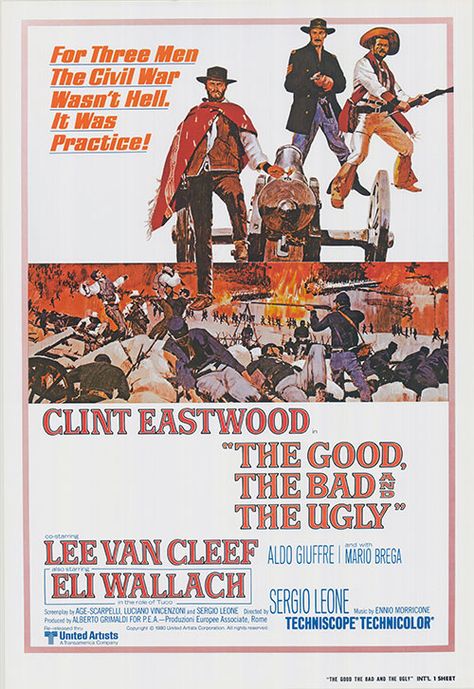

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

While many count For a Few Dollars More as the pinnacle of the Man with No Name Trilogy, nothing beats the epic quality of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly (’68). If we are to believe what Leone always said about his films, that they were “fairytales for adults,” then the final film in his trilogy takes on a mythic quality, augmented by its nearly three hour run time. Standoffs are elongated to build tension, close-ups are even more extreme, often capturing nothing more than the gunfighter’s eyes, and the film moves from a simple hunt for buried treasure to encompass the horrors of war in a panoramic overview of the American Civil War. As the title indicates, Leone and his co-screenwriters maintained the triangulated storyline from the earlier films, this time having Eastwood’s “Blondie” partner with criminal Tuco (Eli Wallach) against a cold-blooded killer (Van Cleef) to locate $200,000 in gold stolen from the Union Army. The on again, off again partnership begins as a scam with Blondie turning Tuco in for a reward, then shooting his noose before he can hang, but relies on mis-trust and betrayal. Leone noted that while the title and the title sequence defines the characters, there are no absolutes in their personalities, giving the film an even richer texture than the early two.

While many count For a Few Dollars More as the pinnacle of the Man with No Name Trilogy, nothing beats the epic quality of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly (’68). If we are to believe what Leone always said about his films, that they were “fairytales for adults,” then the final film in his trilogy takes on a mythic quality, augmented by its nearly three hour run time. Standoffs are elongated to build tension, close-ups are even more extreme, often capturing nothing more than the gunfighter’s eyes, and the film moves from a simple hunt for buried treasure to encompass the horrors of war in a panoramic overview of the American Civil War. As the title indicates, Leone and his co-screenwriters maintained the triangulated storyline from the earlier films, this time having Eastwood’s “Blondie” partner with criminal Tuco (Eli Wallach) against a cold-blooded killer (Van Cleef) to locate $200,000 in gold stolen from the Union Army. The on again, off again partnership begins as a scam with Blondie turning Tuco in for a reward, then shooting his noose before he can hang, but relies on mis-trust and betrayal. Leone noted that while the title and the title sequence defines the characters, there are no absolutes in their personalities, giving the film an even richer texture than the early two.

Leone also felt he was able to make the film he wanted, free from budget restrictions and doubts about his talent and style. The immense success of the earlier films lured American film distributor United Artists in as a financier, providing what would become a $1.3 million dollar budget, more than six times that of Fistful of Dollars. In fact, UA bought the film on the basis of a one sentence story idea of “three rogues looking for some treasure at the time of the American Civil War” (Frayling, p.202). Leone utilized the extra money to create a sweeping and tragic comment on the futility and barbary of war, culminating in the amazing destruction of a bridge dividing the two warring sides, used to maintain a cruel stalemate of deadly attack and retreat death marches.

The bridge itself was actually blown up twice for the production, with the first explosion not captured on film, due to over eagerness of a Spanish army major misinterpreting Leone’s hand gestures. Eastwood and Wallach were to be positioned right near the bridge at the time of the explosion, but after seeing the immense explosion insisted on being right near the camera, just in front of their intrepid director. Once the Spanish army rebuilt the bridge, at their own expense, the crew returned to the site to capture what is seen in the film, complete with flying debris that still nearly engulfs the position where Wallach and Eastwood actually hid and obliterating the location Leone originally wanted them. The scene, complete with the deterministic death of the Union officer, enforces the film’s sentiments towards war and foreshadows the location of the final, iconic scene of the film.

The bridge itself was actually blown up twice for the production, with the first explosion not captured on film, due to over eagerness of a Spanish army major misinterpreting Leone’s hand gestures. Eastwood and Wallach were to be positioned right near the bridge at the time of the explosion, but after seeing the immense explosion insisted on being right near the camera, just in front of their intrepid director. Once the Spanish army rebuilt the bridge, at their own expense, the crew returned to the site to capture what is seen in the film, complete with flying debris that still nearly engulfs the position where Wallach and Eastwood actually hid and obliterating the location Leone originally wanted them. The scene, complete with the deterministic death of the Union officer, enforces the film’s sentiments towards war and foreshadows the location of the final, iconic scene of the film.

While the enormous scope of the film elevates it from the other two, it is Ennio Morricone’s stylistic and memorable score that sets the film apart. Although Morricone had scored the earlier films, using his unique blend of instruments, vocalizations and styles, it is in The Good, The Bad, that his score blends perfectly with the story and the images to create mood and emotion in an unparalleled manner. The iconic melody is repeated throughout, creating tension and anticipation. Morricone was finally recognized with an Oscar in 2016 for his score for Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight (’15), among his more than 500 film scores, none would be more recognizable than The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

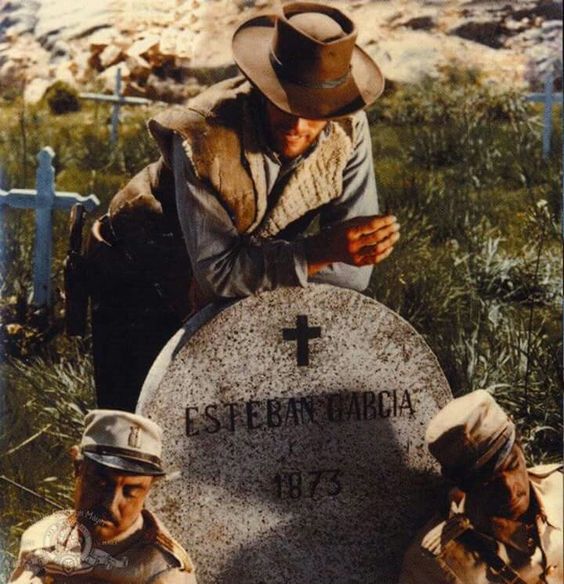

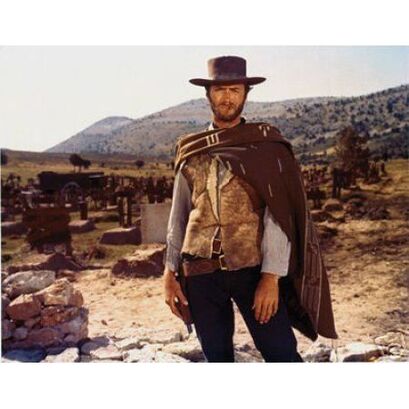

An additional thread running through all three films, but carrying larger weight in The Good, the Bad, is Leone’s subversion of religious iconography to color the space around the story with doom and godlessness. Nowhere is this more pronounced that in the iconic final scene in the Civil War cemetery. Surrounding by the evidence of man’s inhumanity towards his fellow man, the three protagonists duel for the right to take the buried gold. Murder surrounded by murder. Leone uses intense movement as Tuco searches for the grave, creating a dizzying effect for the viewer, an overwhelming sense of the infinite nature of the cemetery and the graves themselves. Even when the three rogues gather in the circle at the center of the cemetery there is no sense of calm because as the music and editing increase so too does the tension and anticipation. Cutting in closer and closer to the rogues, ultimately showing their eyes only, editing more quickly to again create a similarly dizzying effect, Leone creates one of the most intense and beguiling climax in movie history. The final gunshots jerk the viewer into stillness as the one rogue falls.

An additional thread running through all three films, but carrying larger weight in The Good, the Bad, is Leone’s subversion of religious iconography to color the space around the story with doom and godlessness. Nowhere is this more pronounced that in the iconic final scene in the Civil War cemetery. Surrounding by the evidence of man’s inhumanity towards his fellow man, the three protagonists duel for the right to take the buried gold. Murder surrounded by murder. Leone uses intense movement as Tuco searches for the grave, creating a dizzying effect for the viewer, an overwhelming sense of the infinite nature of the cemetery and the graves themselves. Even when the three rogues gather in the circle at the center of the cemetery there is no sense of calm because as the music and editing increase so too does the tension and anticipation. Cutting in closer and closer to the rogues, ultimately showing their eyes only, editing more quickly to again create a similarly dizzying effect, Leone creates one of the most intense and beguiling climax in movie history. The final gunshots jerk the viewer into stillness as the one rogue falls.

In a film full of futility, dishonor, betrayal and double-crosses, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly becomes perfection in the sum of all its parts. It is the culmination of Leone’s trilogy because it best captures and refines the tone and perspective that defined his style. Eastwood’s Man with No Name is the perfect anti-hero, the brother Leone never had, and the antithesis of the traditional Western hero. As noted, there are pieces of the historic Western, but they are circumvented and twisted to form something new, from top to bottom, not just for changes sake, but to expand the very generic definition of a Western. In the generations since Leone launched the Italian Western worldwide, there have been Westerns and action films that have riffed on what Leone created, but none have done it better than the original! Taken together, The Man with no Name trilogy may be the greatest piece of Western film ever created and taken separately, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly itself stands among the 10 best Westerns ever made.