Scarface 1983 & 1932

|

Scarface 1932

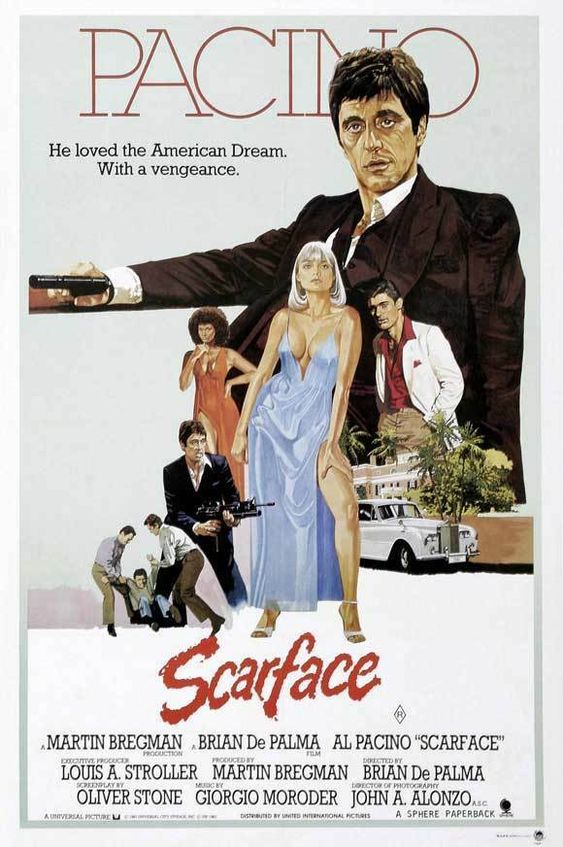

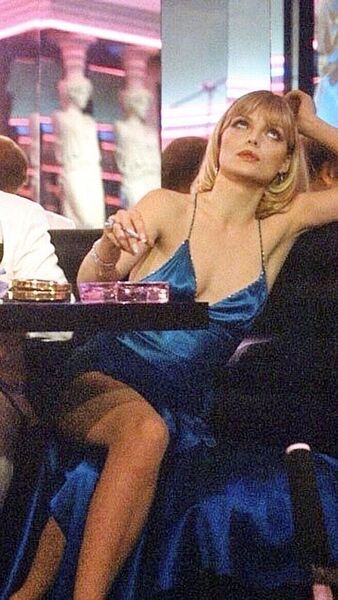

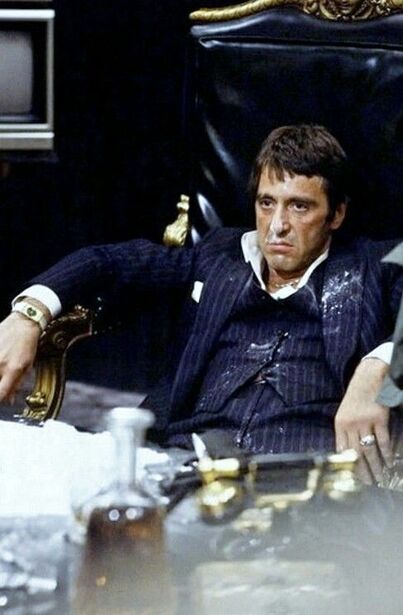

Directed by: Howard Hawks Starring: Paul Muni, Ann Dvorak, George Raft, Keren Morley Written by: Ben Hecht Studio: Universal International IMDB Rating: 8 Scarface 1983 Directed by : Brian DePalma Starring: Al Pacino, Michelle Pfeiffer, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio, Steven Bauer Adapted By: Oliver Stone Studio: Universal IMDB Rating: 8 |

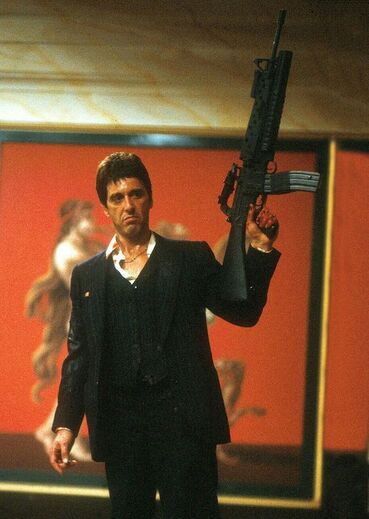

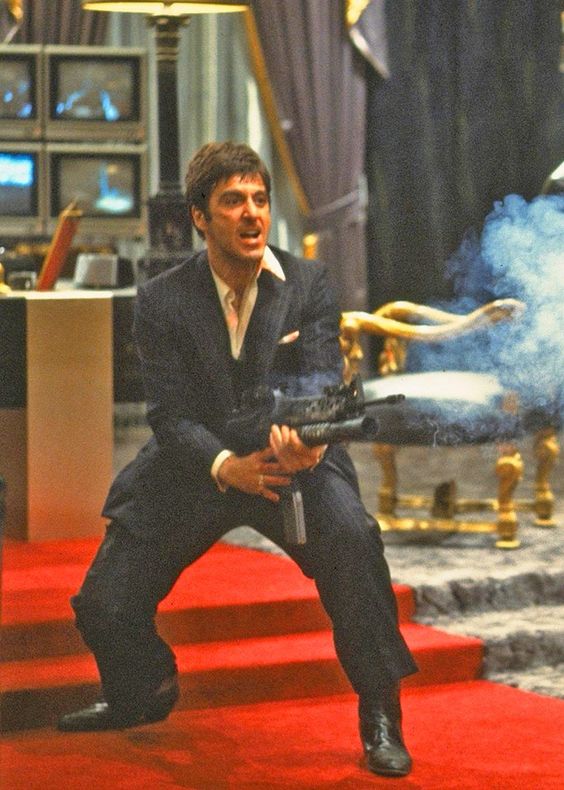

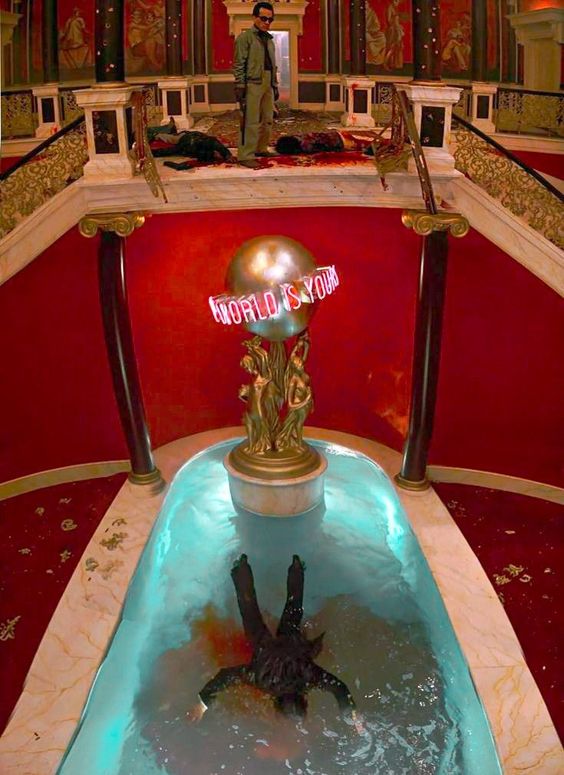

I came across an article about the best films of the 1980’s that listed one film from each year. The list was full of arthouse and foreign titles like The Elephant Man (’80), Ran (’85), Wings of Desire (87) and a personal favorite, Das Boot (’81). One title stood out, however, not because it was a box office smash (It was #40 for 1983), but because it was the only film I remember talking about in school days after it was released. In 1983, I was a high school senior when Brian DePalma’s Scarface opened on December 9th. The purely visceral reaction that many boys my age had to the blood soaked and cocaine fueled story of a Cuban immigrant hell bent on achieving the American dream, would imprint many of them for life. “Say hello to my little friend” became not just a familiar greeting, but a link to a shared experience of a story that fit nicely into the “Greed is Good” decade. Of course, that was not the focus of the discussion during those weeks in December. It was the violence, the overwhelming body and bullet counts, the mounds of cocaine, and of course, Al Pacino’s over the top performance as Tony Montana that fueled the conversations. Nobody read the reviews that pointed to DePalma’s stylized images that would be repeated for the next 5-10 years, most notably in Michael Mann’s Miami Vice TV show. Nobody knew that the film was a pretty straight forward remake of a 1932 classic of the same name by Howard Hawks, substituting cocaine for beer as the illegal substance of the moment. And nobody talked about the moody Gorgio Moroder musical score and how the composer was pretty much creating a template for the soundtrack of the decade. All we talked about was the hotel room shootout that spilled into the street, the nightclub shooting spray of bullets and of course, the climactic explosive shootout in Tony’s mansion, complete with the splash down in a pool of blood, the only suitable ending for so violent a film. Scarface was an experience all unto itself, but put in the context of what it meant as a reflection of the culture of the 1980’s, its homage to film history and director DePalma and screenwriter Oliver Stone’s take on both, would turn an elemental experience into a film classic and cultural touchstone.

Only later would I come to appreciate these things and learn to read into the carnage, the neon lights and swifter than swift rise and fall of the film’s doomed protagonist that what the film was really showing was the rot inherent in an American culture, rooted in consumerism and greed. In rewatching both versions of Scarface recently, it became clear that not much had really changed in the 50 years between them. There was the overt fear of the ‘other’, displaced from another country and culture, running through both films. There was the same undercurrent of the haves and the have nots. And there was a cynicism that was rooted in a distrust of a corrupt local and/or federal government.

Scarface, the man, represented immigrant incursions into illegal enterprises as a means of self-preservation, but also assimilation, which terrified 1930’s Americans, just as it terrified them in the 1980’s (and still today). They talk differently; they eat different foods and have different rituals and beliefs, so they must be up to no good and out to destroy what we hold near and dear. Reflecting these innate fears on screen reinforces a belief system in the viewing public, justifying their distrust in an ever-repeating cycle. Paul Muni’s Scarface character in the 1932 version, Tony Comonte, represented the influx of European immigrants in the early part of the century, just as Pacino’s represented Hispanic (Cuban) immigrants in the later part. In both films there are disdainful mothers representing immigrants who accept their fate as second-class citizens, while condemning their son’s illegal activities, providing a moral high ground in subservience.

Scarface, the man, represented immigrant incursions into illegal enterprises as a means of self-preservation, but also assimilation, which terrified 1930’s Americans, just as it terrified them in the 1980’s (and still today). They talk differently; they eat different foods and have different rituals and beliefs, so they must be up to no good and out to destroy what we hold near and dear. Reflecting these innate fears on screen reinforces a belief system in the viewing public, justifying their distrust in an ever-repeating cycle. Paul Muni’s Scarface character in the 1932 version, Tony Comonte, represented the influx of European immigrants in the early part of the century, just as Pacino’s represented Hispanic (Cuban) immigrants in the later part. In both films there are disdainful mothers representing immigrants who accept their fate as second-class citizens, while condemning their son’s illegal activities, providing a moral high ground in subservience.

Order is represented by corrupt cops who heap scorn and ridicule on the Scarface character, even as they take bribes to look the other way. There is a cynicism at work in including the government representatives in the workings of illegal alcohol/drug trades. In DePlama’s version the cops are so corrupt as to approach Tony in his club, appropriately called Babylon, outlining the rules of their indecent arrangement for protection and disinterest. Corruption, however, must always be balanced, most notably in films in the 1930’s, but no less so in 1983. Even the weak Production Code Administration required an onscreen preamble asking “what are we going to do about it (bootlegging)” in 1932, shifting the responsibility to the viewer, while the arrogant cop in 1983 sits by watching Tony’s boss get gunned down, unafraid for his own wellbeing, which becomes a fatal mistake. The ledgers are balanced, but not forgotten. A final note about DePlama’s version extends its cynicism to the federal government in the form a CIA operative condoning Tony’s trafficking at a meeting in Bolivia, a nod the Reagan era double dealing in Central America.

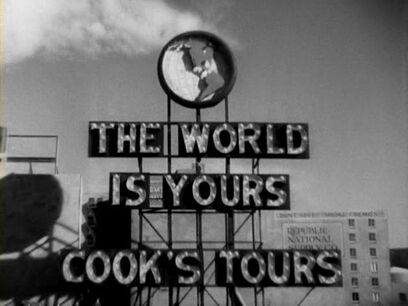

Greed, of course, is universal and certainly not limited to capitalism, although it provides a fertile field to cultivate extreme examples like Scarface. The cost of suits and cars are specifically mentioned in both films as status symbols of wealth. Cigars, no small phallic symbol either, also represent class and taste, with both Scarface’s graduating to superior smokes as they rise to power. Where greed becomes overwhelming for men in both films is in the need to quickly assume control through violence, noting in both cases that their bosses are ‘weak’ and therefore unnecessary. Both films make the point that upsetting the status quo is at the root of chaos and pushes both men towards their destruction. In the case of Tony Comonte, it’s the incursion into north side Chicago that sets off the ultra-violent and destructive war that ultimately gives the police no choice but to hunt him down. For Montana, it’s bypassing the Columbians and seeking product in Bolivia that brings a veritable army down on his house in order to snuff him out. Strangely, it’s Montana’s one moment of self-conscience, his unwillingness to kill innocent children that ultimately leads to his demise. Since both men live by the credo “The World is Yours”, but they both lack the self-awareness to see that in making the world their own, they neglect the natural order and therefore must die.

Greed, of course, is universal and certainly not limited to capitalism, although it provides a fertile field to cultivate extreme examples like Scarface. The cost of suits and cars are specifically mentioned in both films as status symbols of wealth. Cigars, no small phallic symbol either, also represent class and taste, with both Scarface’s graduating to superior smokes as they rise to power. Where greed becomes overwhelming for men in both films is in the need to quickly assume control through violence, noting in both cases that their bosses are ‘weak’ and therefore unnecessary. Both films make the point that upsetting the status quo is at the root of chaos and pushes both men towards their destruction. In the case of Tony Comonte, it’s the incursion into north side Chicago that sets off the ultra-violent and destructive war that ultimately gives the police no choice but to hunt him down. For Montana, it’s bypassing the Columbians and seeking product in Bolivia that brings a veritable army down on his house in order to snuff him out. Strangely, it’s Montana’s one moment of self-conscience, his unwillingness to kill innocent children that ultimately leads to his demise. Since both men live by the credo “The World is Yours”, but they both lack the self-awareness to see that in making the world their own, they neglect the natural order and therefore must die.

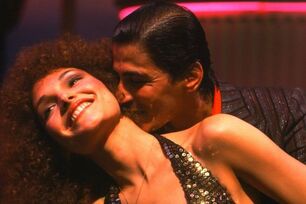

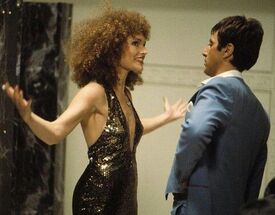

literal line for line re-reading of Hawks’ and writer Ben Hecht’s original film, the most peculiar carryover is Tony’s relationship with his sister. In both films there are obvious incestuous overtones in how he treats his sister and views her sexuality. Hecht and Hawks were controlled by much more conservative censorship rules, but still make it plain to see. Muni’s Tony protects his sister, gives her gifts and ultimately murders his best friend to seemingly protect her virtue. That they die together in a hail of gunshots links them together like two lovers at the conclusion of the 1932 version.

Unrestricted in any way, DePalma and screenwriter Oliver Stone provide what I think is the weak point of their film in the resolution to Gina and Tony’s relationship. With robe open and waving a pistol, Gina is a conflicting presence as she approaches Tony in his office. Her outright recognition of Tony’s feelings for her are obvious and trite, used as a plot device as opposed to an interesting undercurrent. In offering herself to Tony, while firing the pistol she metaphorically flips the script, but to what end? Hecht and Hawks had it right. Gina’s place in Tony’s mansion massacre ultimately holds no meaning and his dying alone in the pool disconnects them.

Unrestricted in any way, DePalma and screenwriter Oliver Stone provide what I think is the weak point of their film in the resolution to Gina and Tony’s relationship. With robe open and waving a pistol, Gina is a conflicting presence as she approaches Tony in his office. Her outright recognition of Tony’s feelings for her are obvious and trite, used as a plot device as opposed to an interesting undercurrent. In offering herself to Tony, while firing the pistol she metaphorically flips the script, but to what end? Hecht and Hawks had it right. Gina’s place in Tony’s mansion massacre ultimately holds no meaning and his dying alone in the pool disconnects them.

1983’s Scarface kicked off what would become the go-to villain in countless movies during the ‘80’s, the narco-terrorist, just as 1930’s films relied on the gangster/bootlegger for criminal shorthand. While many Hollywood remakes borrow and steal from their original, DePlama and Stone make it clear they are paying homage to the original masters, even dedicating the film to them before the final credits. I look back at my initial reaction to the film, completely ignorant of the genius that helped shape it, unaware of the echo of a time 50 years prior and really uninterested in digging much deeper than the garish scenery, the stylized dialogue and the overarching political subterfuge. Sometimes I want to tell my younger self that no piece of art stands alone, but builds upon what came before it. Sure, you can waste almost three pages rolling the building blocks around in your head, but in the end if you like it, you like it. For most people that’s enough. Perhaps I’m still looking for the classroom discussion after each film, this time coming with a little bit of historical context.