The Abbreviated Story of Citizen Kane

|

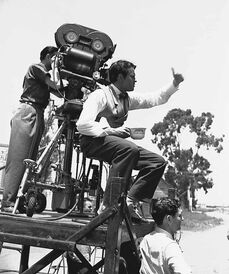

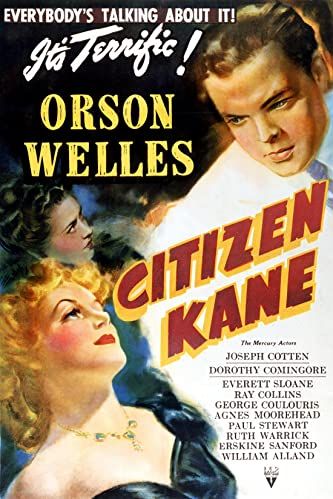

Orson Welles’ masterpiece, Citizen Kane, has been written about, studied & debated for almost 80 years, but the power of the film itself endures as an entertaining and magnificent example of the potential of film & the amazing skills of its creator. While the film cannot be seen as solely made by Welles, his genius is ingrained in the entire production & reflects both his admitted ignorance & fearlessness in filmmaking, but also his showmanship, self-promotion & incredibly unique talents. The story of Citizen Kane is one of a singular triumph wrapped in self destruction, hubris & the push & pull of art versus commerce that has impacted moviemaking for more than 120 years. The story may not be wholly unique, but it happened on such a large scale, impacting an entire industry & a handful of the most creative folks in Hollywood over the course of their lifetimes, while illustrating the enormous power ceded to one man, that Citizen Kane, even if it were not such a fantastic film, would still go down as the most talked about film in moviemaking history.

Called the ‘boy wonder’ by New York drama critics before the age of 24, Welles had already created a mystique around himself that originated in his infancy & carried through his stage career as an actor, his radio productions & his staging of classics as a producer/director. When Hollywood came calling, believing he could do no wrong, while at the same time offering a patina of class, creativity & panache to the movie industry, |

Welles held out for more than a year, before signing the most one-sided contract in motion picture history. Mini-major studio RKO offered Welles complete artistic control of 4 films he would produce for the studio, receive $150,000 per film to do so & would answer to no one in regards to scripting, production, editing or casting. He would be his own boss, calling the shots in a medium he had neither worked in nor had any experience in creating. Reaction in Hollywood was swift & decisively bitter, with newspaper columnists branding the ‘marvelous boy’, as a Time magazine cover story called him, “Little Orson Annie” & other similarly derisive monikers. He was an outcast before stepping foot in California & was even taken to task for his beard, which was immediately deemed pretentious & showy.

Before Welles began work on Citizen Kane, he had several highly publicized false starts, including an attempt to make Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, that only fueled the resentment & ridicule within the moviemaking community. After more than a year, in fact, Welles had neither a script nor project planned & studio wags began to wonder if he would ever produce anything against his once in a century contract. While all of Hollywood turned his back on Welles, an out of work & desperate writer/producer named Herman Mankiewicz, whom Welles had met in New York several years earlier, offered him kindness & Welles rewarded him with a writing job on his continuing radio program. Little did either man know that that mutual kindness would begin the collaboration that would in some way, shape or form, help to create the script for arguably the greatest movie ever made.

Mankiewicz was a noted raconteur who had made his name and initial reputation in New York in the 20’s as part of the famed Algonquin Round Table. He was a brilliant storyteller, who graduated from college in his late teens & wrote for various newspapers & magazines, usually being fired before staying too long. Somehow, he always landed on his feet, despite a prodigious appetite for gambling & alcohol. After leaving New York for greener pastures in Los Angeles, Mank, as he was known, landed as the head of the scenario department at Paramount Pictures, writing title cards for silent films. As sound pictures evolved in the late ‘20’s & early ‘30’s Mank’s stature grew in Hollywood & he worked both credited & uncredited on dozens of films before landing at MGM & penning the adaptation for the all-star classic Dinner at Eight (1933). He was also one of the original writers on Wizard of Oz, most notably suggesting the switch to color film when entering Oz, before being fired for a second time by MGM, leaving LA & getting in a car accident that left him hospitalized or immobilized at home for more than 6 months, which is when he met with Welles once again.

Mankiewicz was a noted raconteur who had made his name and initial reputation in New York in the 20’s as part of the famed Algonquin Round Table. He was a brilliant storyteller, who graduated from college in his late teens & wrote for various newspapers & magazines, usually being fired before staying too long. Somehow, he always landed on his feet, despite a prodigious appetite for gambling & alcohol. After leaving New York for greener pastures in Los Angeles, Mank, as he was known, landed as the head of the scenario department at Paramount Pictures, writing title cards for silent films. As sound pictures evolved in the late ‘20’s & early ‘30’s Mank’s stature grew in Hollywood & he worked both credited & uncredited on dozens of films before landing at MGM & penning the adaptation for the all-star classic Dinner at Eight (1933). He was also one of the original writers on Wizard of Oz, most notably suggesting the switch to color film when entering Oz, before being fired for a second time by MGM, leaving LA & getting in a car accident that left him hospitalized or immobilized at home for more than 6 months, which is when he met with Welles once again.

Both men had the germ of an idea to make a picture examining the legacy of a dead man, with Welles apparently wishing to include multiple perspectives. Preston Sturges has used a broadly similar approach in writing The Power & the Glory that was released in 1933. While the legend of the screenplay is a widely debated topic, the fact that both men settled on William Randolph Hearst as a model seems quite sensible. Mankiewicz was well acquainted with Hearst because he was a regular guest at the newspaper mogul’s ranch at San Simeon while a friend of Hearst’s mistress, actress Marion Davies & Welles had always looked for someone with enough gravitas & notoriety to carry out his grand idea. With the basic premise determined, Welles sent Mankiewicz, at a $1,000 per week salary, producer John Housman & typist Rita Alexander to a ranch in the Mojave Desert, where there would be no distractions & Mank’s drinking could be limited to 1 per day after working. For 3 months Mank worked to create what would be a 300+ page tome encompassing the life of the man who would eventually be called Charles Foster Kane. Later, in editing sessions at Mank’s house in Los Angeles, the script would be pared down to a more manageable shooting length, with Welles further editing it on the set during production. Welles once commented that there were 2 scripts for Citizen Kane, Mankiewicz’s & his & he was ultimately responsible, as the producer, for what ended up on the screen. Pauline Kael, the respected film critic for New Yorker Magazine, writing in her lengthy essay 1971 “Raising Kane,” gave Mankiewicz primary credit for the script, however, citing the inclusion of as much Welles’ personality quirks as Hearst’s life story. Regardless, the finished script was arbitrated by the Writer’s Guild & both Mankiewicz & Welles were awarded co-credit & ultimately shared the Best Screenplay Oscar.

Once production was ready to begin Welles was fortunate to have at his disposal the best of RKO’s technical staff, but his most important technical partner was not on RKO’s payroll, he worked for producer Samuel Goldwyn. Cinematographer Gregg Toland had an already established reputation as one of the best cameramen in Hollywood, having been nominated for 5 Oscars before coming to shoot Citizen Kane, but his contribution far outweighed even those lofty award bona fides. Toland’s ability to interpret & add to Welles’ vision for the film was paramount to the film’s incredibly groundbreaking visual style. Deep focus photography, with different depths in the frame captured in crystal clarity, had been used by Toland before, but Welles pushed the boundaries, particularly in the cavernous sets of Xanadu. Similarly, low angle shots had been used before, most notably in German Expressionist influenced films, but again Toland & Welles utilized these shots to reflect character & mood, as well as atmosphere. Set design, makeup, sound, music & editing were all used to further Welles’ particular vision for the film, but would not have possible without the amazing artists at his disposal. While he shot the film, Welles relied on these studio craftsmen, many of whom would go on to have award winning careers after Citizen Kane, to interpret & reflect what he was trying to do, in some cases expanding on Welles’ ideas. Editor Robert Wise, for instance, won 4 Oscars, including Best Director for both The Sound of Music (’65) & West Side Story (’61). Bernard Herrmann, who composed Kane’s score, won his only Oscar for All That Money Can Buy the same year as Kane released, but is probably most famous for creating the iconic scores for many of Alfred Hitchcock’s films.

Before production began, however, the trouble that has kept Citizen Kane in the popular imagination for 80 years, began in earnest, when a copy of the script was leaked and made its way to representatives of William Randolph Hearst. Rumors had been circulating around Hollywood that Welles’ film would be a scathing takedown of a powerful man, but once the script leaked, whether directly from the always self-destructive Mankiewicz, a bitter studio source or from somewhere else, it created a simmering firestorm that would eventually encompass many of those involved in the film, but also the film itself.

Hollywood gossip columnists Hedda Hopper, who wrote for the Los Angeles Times, & Louella Parsons, who wrote for the Hearst syndicate of papers, could make or break anything or anyone in Hollywood with the power of their massive readerships & seemingly endless access. Hopper had usually treated Welles kindly in her columns, even in the face of Hollywood’s dismissal of the boy genius, but once she was able to see a working print of the film, she reported directly to her paper’s chief rival, William Randolph Hearst, that the film was nothing but a smear campaign against him. The Hearst machine, whether directed by Hearst or not (there is a healthy debate), mobilized to have the film crushed before it could see the light of day. Taking a 3 prong approach that included threats against all the major studios in Hollywood in an effort to suppress the film, the discrediting of Welles personally & finally the absolute destruction of the film itself through the burning of all prints & photographic evidence of its existence. The effort was swift & long lasting & utilized all the power of Hearst’s mighty news machine, a machine that was largely responsible for creating “yellow journalism” in America in the first have of the 20th century.

The first move was to threaten every studio in Hollywood with an absolute boycott of advertising & publicity in every Hearst paper, which could have crippled the studios just as they were losing foreign revenue because of the outbreak of World War II. When pressure mounted, editor Wise took a work print of the film to New York to show the rival studio bosses. Welles made an impassioned plea for his film, but in the end Louis B. Mayer, from MGM, proposed that a studio consortium buy the negative from RKO for more than $800,000, the cost of RKO’s investment in the film. RKO head George Schaefer, in one of the bravest decisions in film history, bypassed his perpetually cash strapped board of directors and turned the offer down flat. Parsons, meanwhile, forced her way into a screening of the film, with Hearst lawyers in tow, in a calculated effort to put legal pressure on RKO to abandon the film. She also wrote vociferously about Welles, the film & RKO in her column, trying to undermine public interest in the film. An offshoot of the threats on the studios, however, was the downstream pressure they were able to apply to not just the theaters they owned, but every independent chain in the county, that showing Kane would risk their ability to get any Hollywood films.

Hollywood gossip columnists Hedda Hopper, who wrote for the Los Angeles Times, & Louella Parsons, who wrote for the Hearst syndicate of papers, could make or break anything or anyone in Hollywood with the power of their massive readerships & seemingly endless access. Hopper had usually treated Welles kindly in her columns, even in the face of Hollywood’s dismissal of the boy genius, but once she was able to see a working print of the film, she reported directly to her paper’s chief rival, William Randolph Hearst, that the film was nothing but a smear campaign against him. The Hearst machine, whether directed by Hearst or not (there is a healthy debate), mobilized to have the film crushed before it could see the light of day. Taking a 3 prong approach that included threats against all the major studios in Hollywood in an effort to suppress the film, the discrediting of Welles personally & finally the absolute destruction of the film itself through the burning of all prints & photographic evidence of its existence. The effort was swift & long lasting & utilized all the power of Hearst’s mighty news machine, a machine that was largely responsible for creating “yellow journalism” in America in the first have of the 20th century.

The first move was to threaten every studio in Hollywood with an absolute boycott of advertising & publicity in every Hearst paper, which could have crippled the studios just as they were losing foreign revenue because of the outbreak of World War II. When pressure mounted, editor Wise took a work print of the film to New York to show the rival studio bosses. Welles made an impassioned plea for his film, but in the end Louis B. Mayer, from MGM, proposed that a studio consortium buy the negative from RKO for more than $800,000, the cost of RKO’s investment in the film. RKO head George Schaefer, in one of the bravest decisions in film history, bypassed his perpetually cash strapped board of directors and turned the offer down flat. Parsons, meanwhile, forced her way into a screening of the film, with Hearst lawyers in tow, in a calculated effort to put legal pressure on RKO to abandon the film. She also wrote vociferously about Welles, the film & RKO in her column, trying to undermine public interest in the film. An offshoot of the threats on the studios, however, was the downstream pressure they were able to apply to not just the theaters they owned, but every independent chain in the county, that showing Kane would risk their ability to get any Hollywood films.

Even as press screenings & private screenings were bringing more fans to the film, public pressure was mounting on RKO to if not destroy the film, then to simply shelve it & eat the costs. The studio repeatedly delayed the release of the film, first to fend off direct attacks & then to actually find theaters that would show the film. After a wide release was scrapped, however, a smaller, 7 city release was planned for May 1st, 1941, a delay of almost 3 months. Gone was the publicity generated by glowing reviews in Time Magazine & countless (non-Hearst) newspapers. Gone was tens of thousands of dollars in advertising booked for earlier release dates. Gone was a photo spread in Life Magazine touting the film. And gone was the opportunity for the film to turn a profit.

When the film did release it did strong initial business, but the footprint was too small to generate enough buzz for a secondary release throughout the country. RKO had renewed hope when the film was nominated for 9 Academy Awards, but it won just the Best Screenplay award for Welles & Mankiewicz that many credited with being token of esteem for Mank alone. In fact, for many of the other awards the film was booed during the ceremony. With all momentum finally wrung form the film, RKO pulled it from release & filed it in their vault. In the end, the film lost just $150,000 against its cost in its initial run, but the damage had been done & the film was branded a loser & Welles a wild spendthrift.

In the aftermath of Citizen Kane, less than a year later George Schaefer was ousted as head of RKO, along with his dream of turning little RKO into a studio that released high quality/high art films. Within a few years RKO did again fall into bankruptcy & was purchased by Howard Hughes, who would largely destroy the studio before disposing of it.

Orson Welles moved on to make The Magnificent Ambersons (many people consider this his true masterpiece), but while he was away making a documentary in South America for the US Government, the new regime at RKO took the film away from Welles, recut it by nearly half, & destroyed all the remaining footage, crippling the film forever. Welles did have a long career in Hollywood, but it would be marred by squabbles with studios, unfinished or never started projects & his pimping his skills as an actor out to the highest bidder in an effort to make money for his next project. While his career can be looked at an example of unmitigated self-inflicted injury, it is also a cautionary tale of too much talent combined with too much hubris…and bad luck.

Citizen Kane, however, was granted a reprieve from oblivion with initial showings on TV in the early 50’s, the almost reverential love for the film by French critics in the late 50’s & finally, by being named the best film ever made in a 1962 Sight & Sound international survey of film critics & insiders, a position the film held for 50 years, until slipping to #2 & being replaced by Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo in 2012.

Sources:

The Brothers Mankiewicz: Hope, Heartbreak & Hollywood Classics. Sydney Ladensohn Stern. University Press of Mississippi. 2019.

Citizen Kane: A Filmmaker’s Journey. Harlan Lebo. Thomas Dunne Books. St. Martin’s Press. 2016.

Raising Kane & Other Essays. Pauline Kael. Marion Boyers Publishing. 1996.

RKO: The Biggest Little Major of Them All. Betty Lasky. Roundtable Publishing. 1989.

The Making of Citizen Kane. Robert L. Carringer. University of California Press. Revised Edition 1996.

This is Orson Welles. Orson Welles & Peter Bogdanovich. Harper Collins. 1993.

When the film did release it did strong initial business, but the footprint was too small to generate enough buzz for a secondary release throughout the country. RKO had renewed hope when the film was nominated for 9 Academy Awards, but it won just the Best Screenplay award for Welles & Mankiewicz that many credited with being token of esteem for Mank alone. In fact, for many of the other awards the film was booed during the ceremony. With all momentum finally wrung form the film, RKO pulled it from release & filed it in their vault. In the end, the film lost just $150,000 against its cost in its initial run, but the damage had been done & the film was branded a loser & Welles a wild spendthrift.

In the aftermath of Citizen Kane, less than a year later George Schaefer was ousted as head of RKO, along with his dream of turning little RKO into a studio that released high quality/high art films. Within a few years RKO did again fall into bankruptcy & was purchased by Howard Hughes, who would largely destroy the studio before disposing of it.

Orson Welles moved on to make The Magnificent Ambersons (many people consider this his true masterpiece), but while he was away making a documentary in South America for the US Government, the new regime at RKO took the film away from Welles, recut it by nearly half, & destroyed all the remaining footage, crippling the film forever. Welles did have a long career in Hollywood, but it would be marred by squabbles with studios, unfinished or never started projects & his pimping his skills as an actor out to the highest bidder in an effort to make money for his next project. While his career can be looked at an example of unmitigated self-inflicted injury, it is also a cautionary tale of too much talent combined with too much hubris…and bad luck.

Citizen Kane, however, was granted a reprieve from oblivion with initial showings on TV in the early 50’s, the almost reverential love for the film by French critics in the late 50’s & finally, by being named the best film ever made in a 1962 Sight & Sound international survey of film critics & insiders, a position the film held for 50 years, until slipping to #2 & being replaced by Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo in 2012.

Sources:

The Brothers Mankiewicz: Hope, Heartbreak & Hollywood Classics. Sydney Ladensohn Stern. University Press of Mississippi. 2019.

Citizen Kane: A Filmmaker’s Journey. Harlan Lebo. Thomas Dunne Books. St. Martin’s Press. 2016.

Raising Kane & Other Essays. Pauline Kael. Marion Boyers Publishing. 1996.

RKO: The Biggest Little Major of Them All. Betty Lasky. Roundtable Publishing. 1989.

The Making of Citizen Kane. Robert L. Carringer. University of California Press. Revised Edition 1996.

This is Orson Welles. Orson Welles & Peter Bogdanovich. Harper Collins. 1993.