|

Directed by: Samuel Fuller

Starring: James Shigeta, Glenn Corbett, Victoria Shaw Released by: Columbia Pictures IMDB Rating: 7 Written for: CMBA Hidden Classics Blogathon (Spring '21) Nutshell Review:

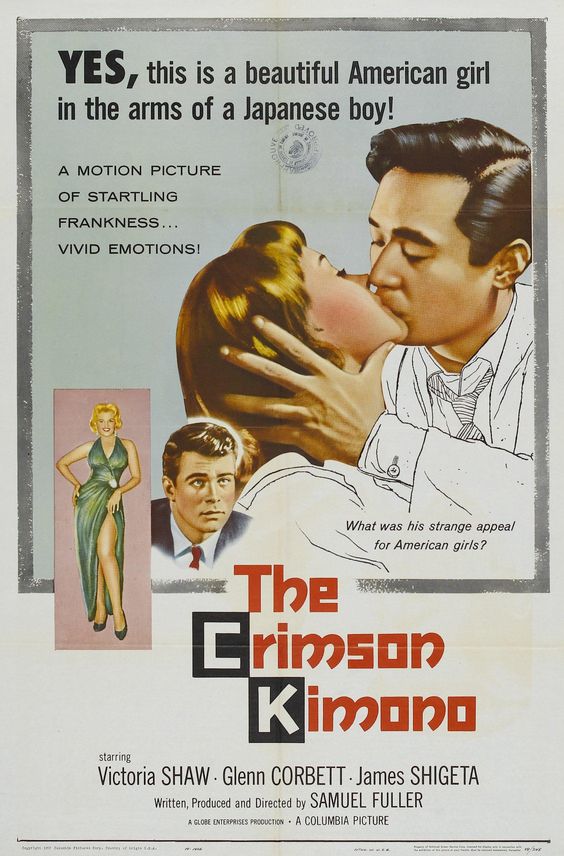

Sam Fuller’s 1959 film The Crimson Kimono has been called a Film Noir, a crime thriller & a police procedural and in its genre bending way it is all three. But at its core, the film is as progressive a film about race & prejudice in America as has ever been made. The fact that it still feels progressive more than 60 years after its release is a tribute to Fuller’s in your face film style &his desire to call out & eliminate hatred of any kind. The Crimson Kimono is the story of 2 Korean war buddies, one a Japanese American (James Shigeta)& the other white (Glenn Corbett), who are both detectives out to solve the murder of a stripper in late ‘50’s Los Angeles. That’s only a pretense, however, for Fuller to explore interracial love in the form of a triangle involving the 2 partners and a Caucasian artist (Victoria Shaw) they both love. While the simple definition of a movie classic may not include The Crimson Kimono because there are no flashy camera flourishes, nor any beautiful prose in the screenplay or memorable performances, what makes the film stand out is its audacious portrayal of racism in such a matter of fact manner. Remember, 1959, the year of the film’s release, was just 3 years after John Wayne played Genghis Khan in The Conqueror & Marlon Brando played a Japanese interpreter in The Teahouse of the August Moon & 2 years before Mickey Rooney’s despicable portrayal of an Asian man in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. For Fuller to not only cast an Asian actor to portray an Asian, but to make him the romantic lead would have been noteworthy enough, but to partner him with a Caucasian woman should be enough for special recognition, if not classic status. |

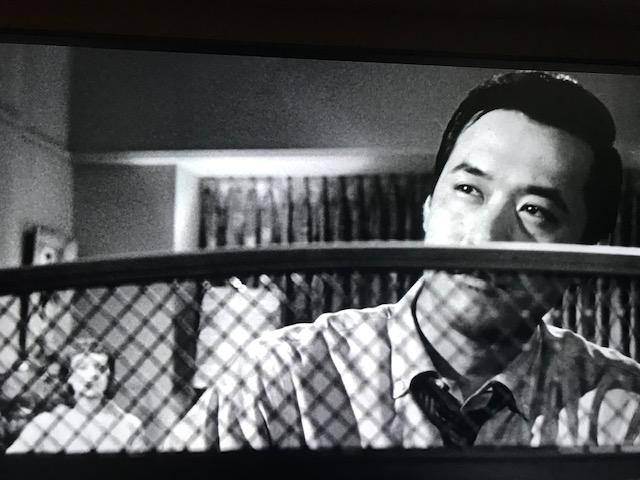

Sam Fuller, for all his tabloid style filmmaking, was a great provocateur, who consistently made a point of calling out hypocrisy & hatred whenever he could & Shigeta’s portrayal of Joe Kojaku is the pinnacle of Fuller’s forthrightness. At points along the story, Kojaku’s self-hatred manifests itself in at first subtle asides, then explodes when he admits his love for Chris & the perceived reaction of partner Charlie Bancroft (Corbett). Because Bancroft makes a point very early in the film abut Joe saving his life & having a pint of Joe’s blood in him, the two men are bonded together & equal, yet Joe questions himself saying “how do I rate a girl like Chris?” when Bancroft has already expressed his love for her. Similarly, Joe implicates himself as even substandard in Japanese culture because he’s not a Kibei, that is born in the US, but educated in Japan. It’s this dual layer of racism/reverse racism that makes Kojaku so interesting; he piles on the self-hatred so thick he cannot see that the world that Fuller creates sees him as a man, and nothing more or less.

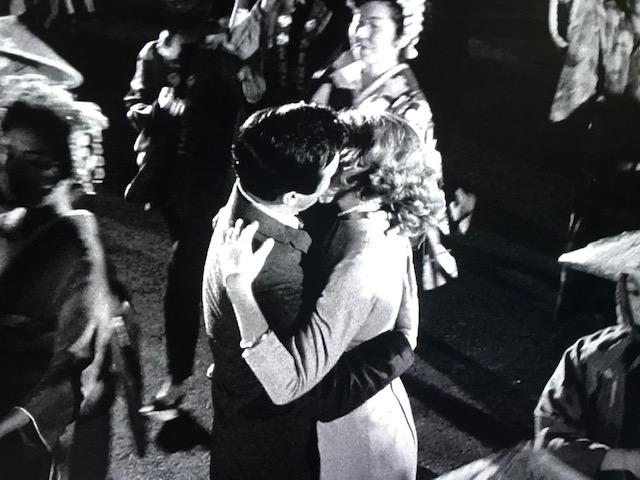

Looking at Kojaku through his own lens, then, the love triangle Fuller sets up becomes even more audacious and enjoyable. Chris is the central witness to the murderer & falls under the protection of Kojaku & Bancroft after her sketch of the killer makes the front page & leads to an assassination attempt. Bancroft is smitten & professes his love for her to everyone but Chris, who seems oblivious. His feelings seem purely physical, however, as he portrays love as much through his lustful eyes as he does in his words or other gestures. Kojaku, on the other hand, is the sensitive pianist, the son of an artist, who shares his ability to see into Chris & moves her emotionally. “Let’s not set off a bomb” is his admission of their shared feelings & the forbidden nature of those feelings. Fuller famously rebuffed Columbia Studio boss Sam Briskin’s request that Bancroft be made more of a “son of a bitch” so as to soften the blow of his losing the girl to an Asian. In doing so, it is plainly clear that Fuller was well aware of the in-your-face nature of the triangle & its outcome. For Fuller, the 2 men are equal & Chris merely chooses the man that she best suited to love.

In Fuller’s world view it ought to be that simple, but to ease the viewer into sharing his beliefs Fuller gently guides the viewer into seeing this way of thinking. Throughout the film are bread crumbs of Japanese culture that draw out its beauty & depth in ways not prevalent in American films of the era. Shooting in LA’s little Tokyo, describing Kendo before the pivotal match between Kojaku & Bancroft takes place & adding Asian figurines, portraits & settings throughout the film are neither accidental nor unintentional. As the film points out several times, looking at things not as you want to see them, but as they really are is the key to happiness & Fuller creates every image to reinforce the idea. Nothing in Fuller’s work is ever subtle or superfluous, so from the opening credits, as the sketch of the geisha in a kimono becomes more complete, Fuller begins the process of filling in the gaps in the viewer’s experience with another culture. He always prided himself on the freedom with which he was able to make his movie & The Crimson Kimono aptly reflects his beliefs and the conviction behind them.

Sadly, in a final effort to rebrand the finished product, Columbia Pictures tagged the movie poster with “YES, this is a beautiful American girl in the arms of a Japanese boy” & in smaller print “What was his strange appeal for American girls?” Fuller admitted his disappointment with the marketing & points to the near simultaneously released & much better known Hiroshima, Mon Amour (Alain Resnais), as proof that his film suffered because of it. While both films feature an interracial couple, perhaps it was America & the Hollywood power brokers, who weren’t ready for what Fuller was putting out, creating the generally accepted classic status of Resnais’ film & the second-tier view of The Crimson Kimono. I’m not trying to say the films are equal, but in trying to capture an American based interracial relationship, on film, in 1959, Fuller perhaps made the more daring film & one worthy of classic consideration.

Sadly, in a final effort to rebrand the finished product, Columbia Pictures tagged the movie poster with “YES, this is a beautiful American girl in the arms of a Japanese boy” & in smaller print “What was his strange appeal for American girls?” Fuller admitted his disappointment with the marketing & points to the near simultaneously released & much better known Hiroshima, Mon Amour (Alain Resnais), as proof that his film suffered because of it. While both films feature an interracial couple, perhaps it was America & the Hollywood power brokers, who weren’t ready for what Fuller was putting out, creating the generally accepted classic status of Resnais’ film & the second-tier view of The Crimson Kimono. I’m not trying to say the films are equal, but in trying to capture an American based interracial relationship, on film, in 1959, Fuller perhaps made the more daring film & one worthy of classic consideration.