Ernst Lubitsch (1892-1947) was primarily known as a director of sophisticated comedies & musicals in the 1930’2 & ‘40’s. In films like Design for Living (’33), Trouble in Paradise (’32) &The Smiling Lieutenant (’31), Lubitsch pushed the bounds of censorship by having his plots creatively revolve around sex, infidelity & adultery. Because his scripts (always working with a collaborating writing who received full screen credit) were smart & the sex always alluded to, but never shown, Lubitsch was able to maintain creative freedom, while never talking down to his audience. At is root this was what was known as “the Lubitsch Touch,” a closed door to imply impending sexual activity, a time lapse of a clock to show the duration of a sexual rendezvous or a couple eating breakfast together after a night of off screen sex. Lubitsch’s films were smarter than the censors, but never too smart for the audience, who appreciated the continental settings, the high class characters & the intelligent dialogue that marked it a Lubitsch film.

While Lubitsch isn’t as well known today as he should being for the most famous & best paid Hollywood director of the 1930’s, his place in film history for hardcore fans will always be cemented through their love for his comedies & musicals. What people may not know, however, is that Lubitsch had an entire separate career as the most famous & popular director in Germany many years before & was the first of the German emigres to come to Hollywood in 1922. His silent films of the late teens & historical spectacles in the early ‘20’s established his as not only a great innovator in silent films, but also direct competition to Hollywood’s greatest directors like Charlie Chaplin & Cecil B. DeMille. It was Mary Pickford who tapped Lubitsch to make his first American film, Rosita, in 1924, relying on Lubitsch’s already evolving sophisticated wit to help establish her as an ‘adult’ star in a more mature role than her audience was used to.

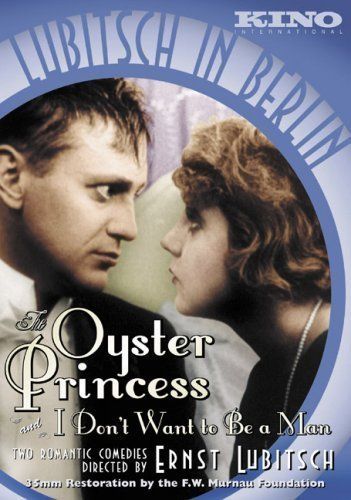

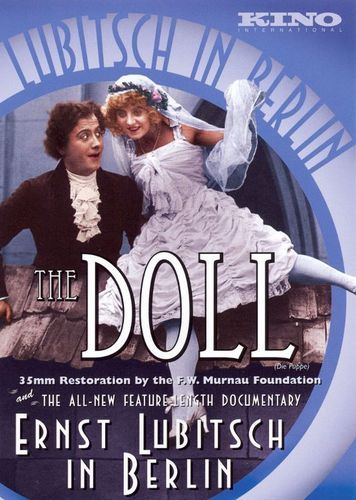

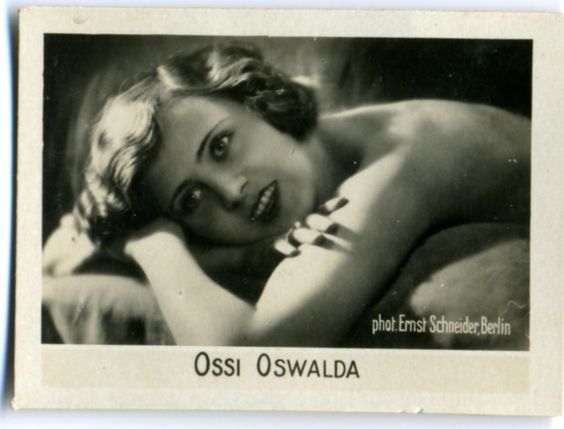

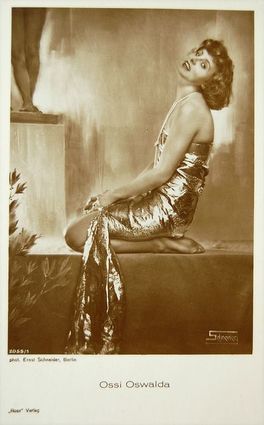

Before Rosita, before Hollywood & even before his spectacles, however, Lubitsch made 3 fantastic silent comedies in Germany, all starring Ossi Oswalda (1897-1947), that were a pure revelation & a joy to watch. They were not his only famous German silent films, as more famous titles like Madame DuBerry (’19), Anna Boleyn (’20) & The Wildcat (’21) helped establish his reputation & Hollywood’s attention, but they are my favorites because of their unbridled enthusiasm, sly innuendo & each shows the germ of The Lubitsch Touch that would become so famous in years to come. The 3 films are I Don’t Want to be a Man (’18), The Oyster Princess (19), & The Doll (’19) & each captures Oswalda’s manic comedy & Lubitsch’s developing touch as a director.

While Lubitsch isn’t as well known today as he should being for the most famous & best paid Hollywood director of the 1930’s, his place in film history for hardcore fans will always be cemented through their love for his comedies & musicals. What people may not know, however, is that Lubitsch had an entire separate career as the most famous & popular director in Germany many years before & was the first of the German emigres to come to Hollywood in 1922. His silent films of the late teens & historical spectacles in the early ‘20’s established his as not only a great innovator in silent films, but also direct competition to Hollywood’s greatest directors like Charlie Chaplin & Cecil B. DeMille. It was Mary Pickford who tapped Lubitsch to make his first American film, Rosita, in 1924, relying on Lubitsch’s already evolving sophisticated wit to help establish her as an ‘adult’ star in a more mature role than her audience was used to.

Before Rosita, before Hollywood & even before his spectacles, however, Lubitsch made 3 fantastic silent comedies in Germany, all starring Ossi Oswalda (1897-1947), that were a pure revelation & a joy to watch. They were not his only famous German silent films, as more famous titles like Madame DuBerry (’19), Anna Boleyn (’20) & The Wildcat (’21) helped establish his reputation & Hollywood’s attention, but they are my favorites because of their unbridled enthusiasm, sly innuendo & each shows the germ of The Lubitsch Touch that would become so famous in years to come. The 3 films are I Don’t Want to be a Man (’18), The Oyster Princess (19), & The Doll (’19) & each captures Oswalda’s manic comedy & Lubitsch’s developing touch as a director.

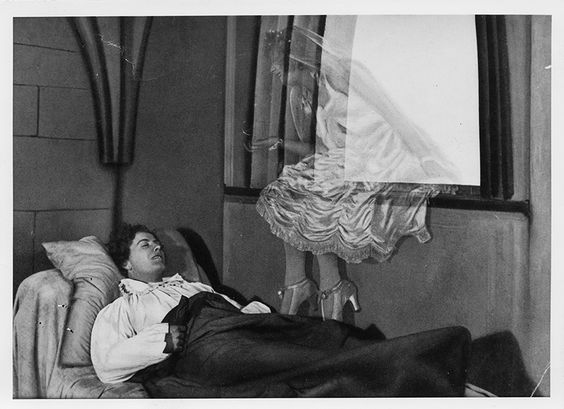

I Don’t Want to be a Man is a subversive little gem that has Oswalda playing a petulant teen who’s absentee uncle appoints a stern guardian to look after. She plays poker, smokes & brazenly talks to stranger men she meets on the street. While she dreams of the freedoms only men have, the stern guardian, Dr. Kersten, strictly enforces every societal norm as he tries to control her. Finding an opportunity to escape she dresses as a young man, in top hat & tails, and heads out on the town to drink, play cards & carry on as only a young man could. Once away from the house & free from social norms Ossi has a fine time, until she comes across her guardian, who doesn’t recognize her. When they both try to woo the same woman, in a twisted game of masculine bravado, they realize they share many of the same beliefs & vices. What ensues is an evening of drunken debauchery, with the 2 ‘men’ carousing & ending up nearly passed out in a cab & taken to each other’s houses, but not before sharing an intimate kiss. Ossi, still in top hat & tails, prefigures several of Marlene Dietrich’s performances in drag in her ‘30’s von Sterberg films (The Blue Angel, Morocco), where her disguise illustrates the characters & by extension the directors feelings toward the fluidity of gender identity & gender roles.

The Oyster Princess is a sly, post WWI poke at American consumerism & satisfaction rolled into a hilarious jabbing of European pomposity & the empty shirt of the royal class. Oswalda stars as the spoiled daughter of the oyster king of America who desperately wants to marry his daughter to European nobility. When a down on his luck & flat broke Prince, wonderfully named Nuki, hears of the opportunity to come into oyster money he sends his secretary to insure Ossi is a suitable companion. What at first starts out as a case of mistaken identity evolves into a catastrophe of engagements, weddings & a disastrous wedding night. In between are marvelous Lubitschian touches of latent & repressed sexuality in Ossi, opportunistic sexual activity on the part of the secretary & the marvelous “Foxtrot Epidemic” dance sequence that simply must be seen to be believed. It’s Busby Berkeley 14 years before Gold Diggers of ’33. Finally, when all is resolved Lubitsch ends his little romp the only way he can, but showing the oyster king looking though the keyhole of his daughter’s bedroom as she enjoys her wedding night.

Finally, there is The Doll, where Lubitsch plays with the very notion of humanity in having Oswalda star as the living incarnation of a mechanical doll. When a shy nephew of the local potentate is tasked with carrying on the family line & forced to marry, he turns to the only logical solution & seeks out the master doll maker, Ossi’s father, to make him a mechanical ‘wife’ to fool the potentate. The dollmaker crafts a lifelike imitation of his daughter, but when it’s broken Ossi impersonates the doll in hilarious fashion, complete with a wedding & the potential for an interesting wedding night. Because the young man has fled to a monastery there is ample opportunity for comedy as Ossi, as the doll, intermingles amongst the cloistered monks. Lubitsch’s genius with The Doll is captured in the opening sequence where Lubitsch himself assembles a scaled down version of the sets where the story takes place, commenting overtly on the artifice that is to come. The Doll is a wonderful commentary of humanity & Oswalda once again provides a stellar performance that’s a little bit manic, a little bit sweet & sentimental and a whole lot of fun to watch.