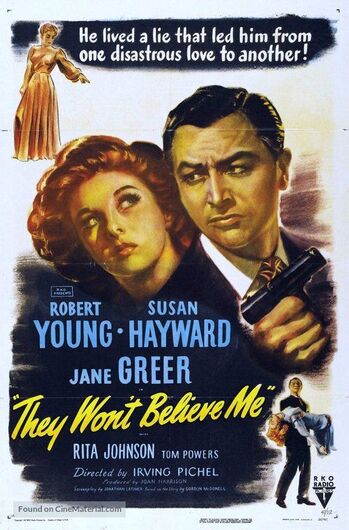

They Won't Believe Me (1947)

|

Released by: RKO Radio Pictures

Directed by: Irving Pichel Starring: Robert Young, Susan Hayward, Jane Greer & Rita Johnson IMDB Rating: 7 They Won’t Believe Me is certainly part of the Film Noir cannon, but it stands alone in how it undermines pretty much all Noir’s standards. In fact, aside from being shot in black and white, the film flips, ignores or subverts pretty much every other element that makes a noir a noir. While it was certainly no accident, the fact that the film was made at the peak of the noir cycle, speaks to a covert and overt effort to stand out and present a completely different perspective on the traditional noir. Made at RKO Radio Pictures, the studio TCM’s Eddie Muller calls “the cradle of Film Noir”, They Won’t Believe Me was the brainchild of producer Joan Harrison, one of the only female producers working in Hollywood in the 1940’s. Harrison’s oversight favorably skewed the traditional perspective of a Film Noir from the male perspective to a subversive commentary on all relationships as transactional, but from a woman’s point of view.

|

Harrison was a twice nominated screenwriter before she turned to producing a string of Films Noir in the 1940’s. She began her career as Alfred Hitchcock’s assistant before quickly rising to indispensable girl Friday and finally to co-screenwriter of 5 of his films. Often called an activist producer because of her intense involvement with all aspects of pre-production, including working with screenwriters, wardrobe supervisors and set decorators, as well as casting directors, Harrison controlled every aspect of the films she produced. According to her biographer Christina Lane, Harrison was “more interested in using the space of the film to explore her deeper interests in character, story, and subjectivity, specifically the relationship between narration and narrator.”( Lane, p. 193) They Won’t Believe Me has often been identified as the peak of her independent producing career primarily because of its unique creation of the ‘homme fatale.’ Robert Young, cast against his good guy image to play philandering husband Larry Ballentine, essentially ruins the lives of three separate women, replacing traditional noir’s murderous female manipulators, with an amoral male protagonist who uses love and lust for personal gain.

The central question in They Won’t Believe Me, however, is whether a murder actually took place, stretching the ‘fatale’ part of ‘homme fatale’ in another subversion of the traditional noir plot. The story is framed by a courtroom recitation told by Ballentine from the witness stand during his murder trial, telling his story of how 2 people ended up dead, but stopping short of fully implicating himself directly. By raising the idea of a self-serving and therefore unreliable narrator, Harrison and screen writer Jonathan Latimer (The Glass Key, Nocturne, The Big Clock) draw upon noir’s use of flashback to illustrate the story, but once again twist things towards their intention of undermining the male point of view. Ballentine’s actions during the shocking final scene seem to indicate even he cannot trust what he put into the world while under oath.

Harrison’s films, including those she worked on with Hitchcock had an over-arching thematic perspective from a female point of view and offered well-rounded three-dimensional female characters, none stronger than the three women in They Won’t Believe Me. A year before Jane Greer created the ultimate femme fatale Kathie Moffat, in 1947’s Out of the Past, she portrays a magazine writer in love with Ballentine, but determined to explain the story of the 2 deaths. Her character has depth, a rich back story outside the plot and reflects the thin line between love and hate. Susan Hayward’s Verna Carlson, on the other hand, makes no bones about her status as a gold digger, playing Ballentine against his business partner Trenton, ironically played by Tom Powers, himself known to noir fans as Mr. Dietrichson from Double Indemnity. She is cold blooded and amoral, transacting for ‘orchids’ with both men, but fatally letting her guard down to love Ballentine. Hayward is fantastic in transitioning from the calculating to the lovelorn, making her sacrifice of money seem real and sincere.

The lynch-pin of the strong female characters, however is Rita Johnson’s Greta Ballentine. As Ballentine’s wife she is well aware of his philandering, but accepts it to a degree, physically moving locations to escape each tryst. She is wealthy and very smart, knowing Ballentine better than anyone and exploiting his love of money to hold him close. They both know the marriage is transactional, giving her happiness and him access to her money, provided he is allowed his extra-curricular relationships. While the source of her money is never spelled out, it is very clear that she has come into it through her intelligence and guile. She is smarter than Larry, but knows to not remind him of it and damage his sensitive ego and weak disposition.

Harrison’s films, including those she worked on with Hitchcock had an over-arching thematic perspective from a female point of view and offered well-rounded three-dimensional female characters, none stronger than the three women in They Won’t Believe Me. A year before Jane Greer created the ultimate femme fatale Kathie Moffat, in 1947’s Out of the Past, she portrays a magazine writer in love with Ballentine, but determined to explain the story of the 2 deaths. Her character has depth, a rich back story outside the plot and reflects the thin line between love and hate. Susan Hayward’s Verna Carlson, on the other hand, makes no bones about her status as a gold digger, playing Ballentine against his business partner Trenton, ironically played by Tom Powers, himself known to noir fans as Mr. Dietrichson from Double Indemnity. She is cold blooded and amoral, transacting for ‘orchids’ with both men, but fatally letting her guard down to love Ballentine. Hayward is fantastic in transitioning from the calculating to the lovelorn, making her sacrifice of money seem real and sincere.

The lynch-pin of the strong female characters, however is Rita Johnson’s Greta Ballentine. As Ballentine’s wife she is well aware of his philandering, but accepts it to a degree, physically moving locations to escape each tryst. She is wealthy and very smart, knowing Ballentine better than anyone and exploiting his love of money to hold him close. They both know the marriage is transactional, giving her happiness and him access to her money, provided he is allowed his extra-curricular relationships. While the source of her money is never spelled out, it is very clear that she has come into it through her intelligence and guile. She is smarter than Larry, but knows to not remind him of it and damage his sensitive ego and weak disposition.

made and independent protagonists throughout 1940’s Hollywood films. While he is singularly focused on money, using his charm for as much entertainment as enhancement, he is a weak and lazy man, as evidenced by his flop sweat and laze fare attitude towards his amorality while testifying. Young utilizes all the affable charm that helped make him everyone’s favorite TV dad (Father Knows Best), but because Ballentine is hollow at his core the performance asks more of him and he delivers. The moment he realizes Verna has not cashed the check there is a subtle change in his disposition as he calculates what to do next. For an instant, he appears ready to dump her, but then succumbs to love and relents, momentarily redeeming the seemingly unredeemable schemer. Similarly, when he awakes in the hospital and is confronted by the horrible accident, there is a similar flicker, but this time it’s a flicker of opportunity, opportunity that eventually seals his fate. In both cases it is Young’s simple facial gestures that tell the complete story of Larry Ballentine.

deaths of two people, the censors of the Production Code Administration were all over Harrison at every step of pre-production. Even Harrison’s 21-page synopsis elicited a near death knell for the project when Joseph Breen, the head of the PCA, responded that the story is “almost completely devoid of anything that suggests reasonable respect-or even recognition- of the common amenities of life, to say nothing of the seriousness, the dignity or the importance of marriage.” (Lane, p. 195). Later suggestions for the script included, “make Janice a moral voice”, “eliminate places where Verna and Larry ‘pretend’ to be married” and “delete lines where Gretta condones Larry’s affairs.” An early script also contained Verna asking Larry if he “even had enough strength to come to work” after a romantic night together (p.195). Needless to say, that line never came close to the final shooting script, but shows the games often played with the PCA; putting over the top lines and scenes into early drafts to get what really mattered into the final script. Lane estimates that Harrison generally ignored four out of every five demands for changes or deletions from the PCA. It’s no surprise, however, that the moral voice is the only character standing at the end of the film, such was life under the PCA.

deaths of two people, the censors of the Production Code Administration were all over Harrison at every step of pre-production. Even Harrison’s 21-page synopsis elicited a near death knell for the project when Joseph Breen, the head of the PCA, responded that the story is “almost completely devoid of anything that suggests reasonable respect-or even recognition- of the common amenities of life, to say nothing of the seriousness, the dignity or the importance of marriage.” (Lane, p. 195). Later suggestions for the script included, “make Janice a moral voice”, “eliminate places where Verna and Larry ‘pretend’ to be married” and “delete lines where Gretta condones Larry’s affairs.” An early script also contained Verna asking Larry if he “even had enough strength to come to work” after a romantic night together (p.195). Needless to say, that line never came close to the final shooting script, but shows the games often played with the PCA; putting over the top lines and scenes into early drafts to get what really mattered into the final script. Lane estimates that Harrison generally ignored four out of every five demands for changes or deletions from the PCA. It’s no surprise, however, that the moral voice is the only character standing at the end of the film, such was life under the PCA.

Harrison’s biographer Lane notes that They Won’t Believe Me “simultaneously inhabits and subverts the tropes of the noir genre” utilizing fundamental structural elements, but upending them with often surprising consequences. It is a unique movie in many ways and stands out within the noir cycle for its placing the male character as the driving force of chaos, fueled by the same greed often ascribed to female noir characters, but allowing for a minutia of remorse. Breen had it right by noting that each character and the movie as a whole subverts societal norms regarding marriage and relationships, but isn’t that the point of a good yarn? Larry Ballentine may not be the most reliable narrator/witness, but the fact that he’s forced to justify his actions to save his own life is a win for an alternative perspective.

Souce:

Phantom Lady: Hollywood Producer Joan Harrison, the Forgotten Woman Behind Hitchcock. Christina Lane. Chicago Review Press. 2020.

Dark City: The Forgotten World of Film Noir Revised and Expanded Edition. Eddie Muller. Running Press. 2021.

Souce:

Phantom Lady: Hollywood Producer Joan Harrison, the Forgotten Woman Behind Hitchcock. Christina Lane. Chicago Review Press. 2020.

Dark City: The Forgotten World of Film Noir Revised and Expanded Edition. Eddie Muller. Running Press. 2021.