Frank Borzage's Moonrise: THE ACCIDENTAL NOIR

A 1997 article in Film Comment magazine asked the question if director Frank Borzage had any relevance for modern film watchers. Borzage was a melodramatist whose films valued romance & love above story and realism, but he was a 2-time Best Director Oscar winner (7th Heaven ’29 & Bad Girl ’31), who directed more than 100 films in a career that lasted nearly 45 years & spanned the silent era through the studios’ golden age (1915-1959). The writer (Kent Jones) went on to assert that along with Nicholas Ray (In A Lonely Place ‘50, Rebel Without a Cause ‘55), Borzage was the only “obsessive artist”, whose canon forms a continuous philosophy of life as driven by love above all else. His films existed as a reflection of the times he lived in, but he persevered even after the filmgoing culture changed around him. Ultimately, the writer determined that Borzage is worth knowing, if only to appreciate the sheer artistry of his “lyrical abstraction.” In the context of Film Noir, however, Borzage is worth remembering because, while he worked within the structure of Film Noir, he bent the movement to his own needs & crafted a wonderful film that blends his life’s work with a reflection of the current sentiments around him.

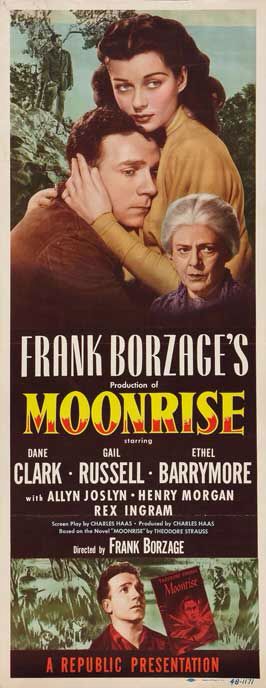

How does such a director create, with Moonrise, one of perhaps the 50 best Films Noir, a movement filled with nihilism, darkness, deceit & death, you may ask? Well, it’s a story as old as Hollywood & reflects the core of Jones’ initial question because by World War II Borzage had fallen out of favor in Hollywood & with the movie going public. His overly romantic style didn’t suit the more cynical times brought about by the war & the award-winning director, who had made films for gold standard studios like Fox, MGM & Paramount in the ‘30’s, was forced to take a 3-picture deal at poverty row studio Republic Pictures to continue working. While he was given lavish budgets by Republic standards, they were a mere pittance to what he was used to & the first 2 films in the deal (I’ve Always Loved You ’46, That’s My Man ’47) were both critical & commercial failures. Borzage agreed to direct Moonrise for the sole purpose of getting out of the contract & was only asked to direct Moonrise after the rights owners couldn’t afford Academy Award winning director William Wellman (Wings ’27, The Public Enemy ’31, A Star is Born ’37), nor their desired star, John Garfield (Force of Evil ‘48, Body & Soul ’48).

Right away there was a natural conflict with the director’s stated filmic style & the story of the son of a hanged murderer, who struggles to overcome that shadow in a small Virginia town. Borzage opens the film with one of the most incredible montages in any film that I can remember & sets the tone for what follows.

In the reflection of a puddle 3 men walk slowly as the camera pans to their feet being pelted with rain. As they climb steps, the camera pans further to the shadow of gallows just as a man is having a noose slipped around his neck. A second man is visible at the switch, pulling it just as the picture cuts to a hanging object over a crying baby’s crib. Once again, the camera pulls back, this time revealing the dangling object is merely a stuffed animal. I

t’s an amazing sequence that reflects what hangs over baby Danny’s head will stay with him throughout his life. It’s a shocking & jarring opening and quickly signals that this isn’t just any Borzage melodrama.

What follows is a quick montage of Danny’s being tormented for his father’s hanging by progressively aging children, most notably a boy named Jerry Sykes. Superimposed over each beating are the feet of the men moving towards the gallows, with the final confrontation taking place as young adults in the woods that sets the plot in motion with the death of Jerry Sykes (Lloyd Bridges). Shot primarily on studio sets to save money, the entire film has the artificiality that was typical of Borzage, but as shot by William Daniels (known primarily as Greta Garbo’s cameraman) that artificiality is transformed into a claustrophobic web pressing down on Danny, suffocating him from within. The swamp where the murder takes place, and where Danny latter flees, is a tangled mesh of branches, low hanging trees & dark water, meant to represent both Danny’s muddy thoughts and a dark pool sucking him under. Even the few interiors in the film don’t offer Danny relief, as he is often framed behind hanging items or shards of darkness that entrap him.

The inevitability of this oppression is entirely counter to Borzage’s worldview, but he places a light in his path, in the form of Gilly Johnson (Gail Russell), the local school teacher, whom Danny loves. She becomes not a savior for Danny, but a driving force that propels him, whether for ill or, eventually, for good. She represents the love and romanticism of Borzage that elevates Moonrise away from pure Noir affects into something unique & redemptive.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention 2 very important supporting characters that also seem unique in the Noir canon. The first is swamp dwelling philosopher Mose, played by Rex Ingram, in what he called the most nuanced part given an African American in American films of the era. Mose is a father figure and a moral compass for Danny, who most notably tells Danny that to resign from the human race is the greatest crime of all. The second is the deaf & dumb Billy Scripture (Harry Morgan), who reflects Danny’s childlike worldview in his desire to please and be cared for. Danny’s defense of Billy while he is being bullied shows Danny’s only selfless act of true tenderness, asking for nothing in return from Billy, but protecting him nonetheless.

This is rather longer than I set out to write, but Moonrise is an important film that I had not seen before. It’s very different in many ways from the typical Noir, as noted above, but it’s the feeling you get watching it that signals its uniqueness. Yes, there is murder, doom & foreboding, but there is also redemption. A redemption, unfortunately, that sealed the fate of the film at the time of its release. Neither critics, nor audiences took to the film & it essentially forced Borzage to retire (or walk away) from filmmaking for almost 10 years. He got out of his contract, but he left a lasting masterpiece, his last, for Film Noir fans to discover & enjoy.

A 1997 article in Film Comment magazine asked the question if director Frank Borzage had any relevance for modern film watchers. Borzage was a melodramatist whose films valued romance & love above story and realism, but he was a 2-time Best Director Oscar winner (7th Heaven ’29 & Bad Girl ’31), who directed more than 100 films in a career that lasted nearly 45 years & spanned the silent era through the studios’ golden age (1915-1959). The writer (Kent Jones) went on to assert that along with Nicholas Ray (In A Lonely Place ‘50, Rebel Without a Cause ‘55), Borzage was the only “obsessive artist”, whose canon forms a continuous philosophy of life as driven by love above all else. His films existed as a reflection of the times he lived in, but he persevered even after the filmgoing culture changed around him. Ultimately, the writer determined that Borzage is worth knowing, if only to appreciate the sheer artistry of his “lyrical abstraction.” In the context of Film Noir, however, Borzage is worth remembering because, while he worked within the structure of Film Noir, he bent the movement to his own needs & crafted a wonderful film that blends his life’s work with a reflection of the current sentiments around him.

How does such a director create, with Moonrise, one of perhaps the 50 best Films Noir, a movement filled with nihilism, darkness, deceit & death, you may ask? Well, it’s a story as old as Hollywood & reflects the core of Jones’ initial question because by World War II Borzage had fallen out of favor in Hollywood & with the movie going public. His overly romantic style didn’t suit the more cynical times brought about by the war & the award-winning director, who had made films for gold standard studios like Fox, MGM & Paramount in the ‘30’s, was forced to take a 3-picture deal at poverty row studio Republic Pictures to continue working. While he was given lavish budgets by Republic standards, they were a mere pittance to what he was used to & the first 2 films in the deal (I’ve Always Loved You ’46, That’s My Man ’47) were both critical & commercial failures. Borzage agreed to direct Moonrise for the sole purpose of getting out of the contract & was only asked to direct Moonrise after the rights owners couldn’t afford Academy Award winning director William Wellman (Wings ’27, The Public Enemy ’31, A Star is Born ’37), nor their desired star, John Garfield (Force of Evil ‘48, Body & Soul ’48).

Right away there was a natural conflict with the director’s stated filmic style & the story of the son of a hanged murderer, who struggles to overcome that shadow in a small Virginia town. Borzage opens the film with one of the most incredible montages in any film that I can remember & sets the tone for what follows.

In the reflection of a puddle 3 men walk slowly as the camera pans to their feet being pelted with rain. As they climb steps, the camera pans further to the shadow of gallows just as a man is having a noose slipped around his neck. A second man is visible at the switch, pulling it just as the picture cuts to a hanging object over a crying baby’s crib. Once again, the camera pulls back, this time revealing the dangling object is merely a stuffed animal. I

t’s an amazing sequence that reflects what hangs over baby Danny’s head will stay with him throughout his life. It’s a shocking & jarring opening and quickly signals that this isn’t just any Borzage melodrama.

What follows is a quick montage of Danny’s being tormented for his father’s hanging by progressively aging children, most notably a boy named Jerry Sykes. Superimposed over each beating are the feet of the men moving towards the gallows, with the final confrontation taking place as young adults in the woods that sets the plot in motion with the death of Jerry Sykes (Lloyd Bridges). Shot primarily on studio sets to save money, the entire film has the artificiality that was typical of Borzage, but as shot by William Daniels (known primarily as Greta Garbo’s cameraman) that artificiality is transformed into a claustrophobic web pressing down on Danny, suffocating him from within. The swamp where the murder takes place, and where Danny latter flees, is a tangled mesh of branches, low hanging trees & dark water, meant to represent both Danny’s muddy thoughts and a dark pool sucking him under. Even the few interiors in the film don’t offer Danny relief, as he is often framed behind hanging items or shards of darkness that entrap him.

The inevitability of this oppression is entirely counter to Borzage’s worldview, but he places a light in his path, in the form of Gilly Johnson (Gail Russell), the local school teacher, whom Danny loves. She becomes not a savior for Danny, but a driving force that propels him, whether for ill or, eventually, for good. She represents the love and romanticism of Borzage that elevates Moonrise away from pure Noir affects into something unique & redemptive.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention 2 very important supporting characters that also seem unique in the Noir canon. The first is swamp dwelling philosopher Mose, played by Rex Ingram, in what he called the most nuanced part given an African American in American films of the era. Mose is a father figure and a moral compass for Danny, who most notably tells Danny that to resign from the human race is the greatest crime of all. The second is the deaf & dumb Billy Scripture (Harry Morgan), who reflects Danny’s childlike worldview in his desire to please and be cared for. Danny’s defense of Billy while he is being bullied shows Danny’s only selfless act of true tenderness, asking for nothing in return from Billy, but protecting him nonetheless.

This is rather longer than I set out to write, but Moonrise is an important film that I had not seen before. It’s very different in many ways from the typical Noir, as noted above, but it’s the feeling you get watching it that signals its uniqueness. Yes, there is murder, doom & foreboding, but there is also redemption. A redemption, unfortunately, that sealed the fate of the film at the time of its release. Neither critics, nor audiences took to the film & it essentially forced Borzage to retire (or walk away) from filmmaking for almost 10 years. He got out of his contract, but he left a lasting masterpiece, his last, for Film Noir fans to discover & enjoy.