A Comparison of The Killers 1946 & 1964

|

The Killers 1946:

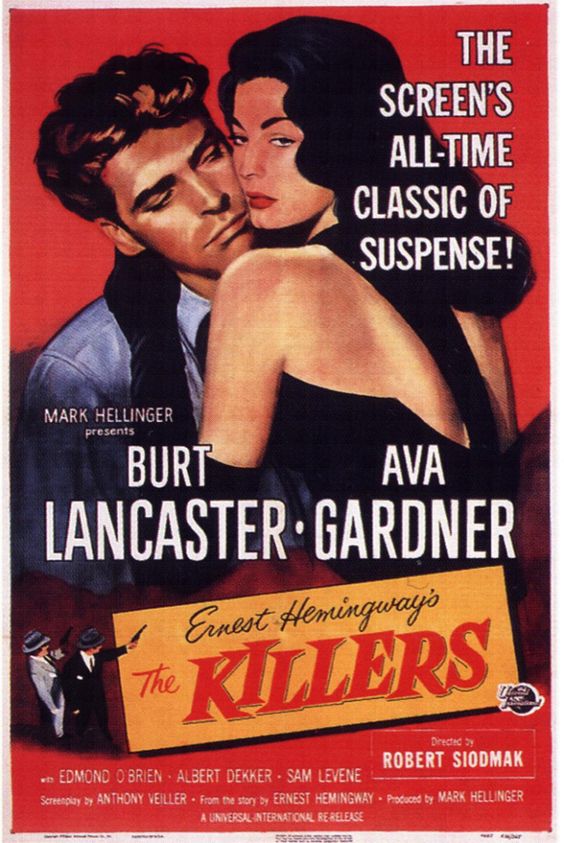

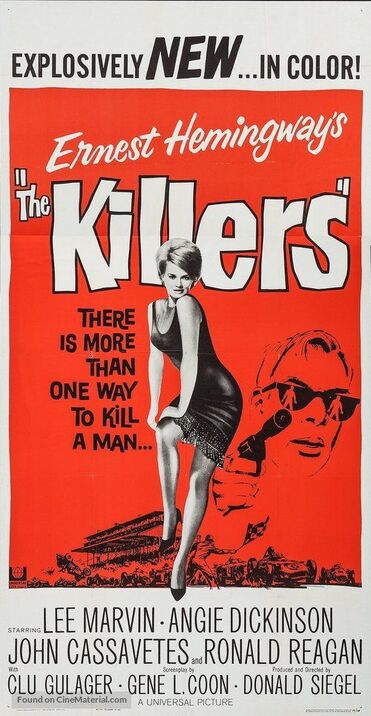

Director: Robert Siodmak Starrring: Burt Lancaster, Ava Gardner Studio: Universal IMDB Rating: 10 The Killers 1964: Director: Don Siegel Starring: Lee Marvin, Angie Dickenson, Ronald Reagan, Clu Kulager Studio: Universal IMDB Rating: 6 I’ve written quite a bit about the 1946 version of The Killers, including citing it as my favorite Film Noir of the classic era (1940-1958) & had never seen Don Siegel’s 1964 remake until recently. Both films were loosely based on the thread of Hemingway’s very short story of 2 killers who arrive in a small town to execute a man who accepts his fate and refuses to run. That’s it. That’s Hemingway’s story. There is no femme fatale; there is no crime. There is no backstory whatsoever, just the Hemingway code of masculinity that says fate should be attacked head on & accepted for what it is. As a montage editor at Warner Bros. in the mid-40’s Siegel wrote a story idea that he hoped to direct. Warner instead sold the story to Universal Pictures, where Siodmak, along with screenwriters Anthony Veiller & John Huston (uncredited), turned it into what has been called, “the Citizen Kane of Film Noir.” Since Siegel had the original concept of creating a back story for the characters in Hemingway’s story, he must be given credit for the imaginative idea of exploring what would drive a man to accept Hemingway’s code of inevitability.

|

Whereas Siodmak turned that idea into a Noir classic, by the time Siegel circled back around to The Killers, some 17 years later, much had changed in the landscape of the country and in moviemaking, impacting his version greatly. Gone were the imaginative chiaroscuro lighting effects that created ominous danger. Gone as well was the dominating sexuality of Ava Gardner’s star making performance as Kitty Collins, manipulating the helpless men in her orbit. Finally, gone was the intricate plotting built on a web of flashbacks within flashbacks, guiding the story to its inevitable conclusion. Instead, Seigel created an anti-Siodmak version of The Killers, flattening the scenery, washing out the images and simplifying the storyline. In doing so, however, Siegel put a stake in the ground for a new movement in film, by twisting and evolving the codes of Film Noir into something different and more reflective of a modern sensibility called Neo-Noir.

In my opinion, 4 significant differences in the two version of The Killers define the change between classic Film Noir and what has been defined as Neo-Noir; the structure, the style, the casting and the sensability. Foster Hirsch writes in Detours and Lost Highways: A Map of Film Noir that one of the defining elements of Film Noir & its descendants is the ability to reflect the mood and tenor of the era. Whereas the classic Noir era echoed the disillusion of post-depression & post-World War II American sentiment, Neo-Noir has moved through the decades mirroring each subsequent decade; the burgeoning distrust of corporate America in the 60’s, the cynical understanding of government in the 70’s & the disdain for greedy capitalism in the 80’s, for instance.

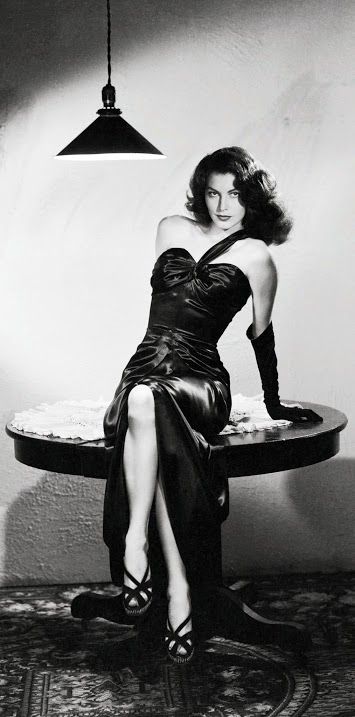

Such is the case with Siegel’s version, as his focus shifts from the dead man’s perspective and what brought about his demise in Siodmak’s version, to the cold blooded and corporate structure of the killers’ enterprise. Ronald Regan, in his last movie role, plays the cold and emotionless leader of the criminal enterprise with banal disinterest. He’s a stuffed shirt, a suit, willing to exploit those beneath him for profit. He’s meant to Illicit disdain from the viewer, more than malevolent evil, which encapsulates the overall sentiment during the ‘60’s to distrust authority more than fear it. Similarly, the killers themselves operate as a mini-vigilante corporation of their own, cruel and calculating as they move from job to job. That they are the propellent of the story speaks to the hollowness of that corporate message because money/profit is put above humanity. Siodmak’s film, on the other hand, focuses on emotion, rather than greed. The Swede’s (Lancaster) entire life is wrapped up in Kitty (Gardner) and his love for her. His final demise is drenched in the realization that she is no longer his. She is dangerous and threatening not just to The Swede, but to every man she encounters, just as classic Noir would have it. In the mid-40’s, heroes were returning from war to encounter a society that had largely forgotten their place in it. Women were in the workplace, were more independent and therefore, more dangerous. Femme Fatales like Kitty, were all over classic Noir & reflect male angst & the threat to traditional male/female roles.

Such is the case with Siegel’s version, as his focus shifts from the dead man’s perspective and what brought about his demise in Siodmak’s version, to the cold blooded and corporate structure of the killers’ enterprise. Ronald Regan, in his last movie role, plays the cold and emotionless leader of the criminal enterprise with banal disinterest. He’s a stuffed shirt, a suit, willing to exploit those beneath him for profit. He’s meant to Illicit disdain from the viewer, more than malevolent evil, which encapsulates the overall sentiment during the ‘60’s to distrust authority more than fear it. Similarly, the killers themselves operate as a mini-vigilante corporation of their own, cruel and calculating as they move from job to job. That they are the propellent of the story speaks to the hollowness of that corporate message because money/profit is put above humanity. Siodmak’s film, on the other hand, focuses on emotion, rather than greed. The Swede’s (Lancaster) entire life is wrapped up in Kitty (Gardner) and his love for her. His final demise is drenched in the realization that she is no longer his. She is dangerous and threatening not just to The Swede, but to every man she encounters, just as classic Noir would have it. In the mid-40’s, heroes were returning from war to encounter a society that had largely forgotten their place in it. Women were in the workplace, were more independent and therefore, more dangerous. Femme Fatales like Kitty, were all over classic Noir & reflect male angst & the threat to traditional male/female roles.

More significant that sensibility, however, in the shift from Classic Noir to Neo-Noir, is storytelling structure. While Classic Noir often twisted timelines (Out of the Past ‘47), redoubled over the same scenes from different perspectives (The Killing ‘56), or told most of the story as a confession (Double Indemnity ‘44), Neo-Noir more often than not used standard linear storytelling, with minor variations. Both versions of The Killers are archetypes of their respective movements, with Siodmak’s version using the device of an insurance investigation to revisit the Swede’s life through interviews, while Siegel’s has the killers’ themselves filling gaps, with only a singular flashback to paint the picture. Where the genius of Siodmak’s version truly separates itself from the other films of its era is by layering flashbacks within flashbacks to paint the entire picture of the Swede’s total infatuation with Kitty. Told by the Swede’s former girlfriend, the encounter when he & Kitty meet is a masterclass in longing, rejection, and sexual heat. Gardner easily provides Kitty’s heat, but it is the look Lancaster casts at Kitty that could stop a train. Because the entire scene is filtered through the girlfriend’s memory, however, it only adds to the bitter sense of irony about what is to come for the Swede as the she looks back in the retelling. Similarly, the Swede’s boyhood friend, now a detective, runs across the Swede covering for Kitty’s crime and is forced to arrest his friend, all the while knowing Kitty’s control over his friend, shaking his head as he recounts the scene. The subjective nature of both flashbacks color them with regret, but foreshadow Kitty’s effect on the Swede’s life.

Siegel’s version’s linear makeup defuses regret from the equation and portrays the doomed race car driver, Johnny North (John Cassavettes), on a march towards death, his fate sealed by his apparent somnambulism. The chronological telling reveals a simple story and lessens the mystery, the tension & the emotional impact on the central couple. In fact, the opening sequence in both films reveals much about how the stories will be told. Siodmak’s uses an almost line for line reading of Hemingway’s short story, laying out the mood, the setting & the tenor of what will come. The killers’ entrance into a non-descript town represents finality. They present as harbingers of death, execute the mark and disappear, casting the rest of the story as prelude, told in flashbacks that illuminate as much as foreshadow. Siegel, on the other hand, has the opening hit take place at a school for the blind, a literal comment on the viewer being blindly led by the sighted killers. That killing tracks as prelude to the discovery that comes in the form of the killers’ exploration. The peeling of the onion leads not just to the demise of Johnny North, necessarily, but to a raft of money. Johnny’s reason for dying becomes a symbolic McGuffin once the killers latch onto the possibility of a larger score, lessening the impact of the opening and the search for Johnny’s state of mind.

Siegel’s version’s linear makeup defuses regret from the equation and portrays the doomed race car driver, Johnny North (John Cassavettes), on a march towards death, his fate sealed by his apparent somnambulism. The chronological telling reveals a simple story and lessens the mystery, the tension & the emotional impact on the central couple. In fact, the opening sequence in both films reveals much about how the stories will be told. Siodmak’s uses an almost line for line reading of Hemingway’s short story, laying out the mood, the setting & the tenor of what will come. The killers’ entrance into a non-descript town represents finality. They present as harbingers of death, execute the mark and disappear, casting the rest of the story as prelude, told in flashbacks that illuminate as much as foreshadow. Siegel, on the other hand, has the opening hit take place at a school for the blind, a literal comment on the viewer being blindly led by the sighted killers. That killing tracks as prelude to the discovery that comes in the form of the killers’ exploration. The peeling of the onion leads not just to the demise of Johnny North, necessarily, but to a raft of money. Johnny’s reason for dying becomes a symbolic McGuffin once the killers latch onto the possibility of a larger score, lessening the impact of the opening and the search for Johnny’s state of mind.

If structure and sensibility help to mark the decade in which both films were made, then casting shows the change in the Studio System over the course of nearly 2 decades. While Siodmak’s version was made in the heyday of the studio system, it also was reflective of tiny, but perceptible cracks in the system. Independent producers like Mark Hellinger were churning out cheaper product than in-house studio teams and pushing boundaries in style and content, as part of the bargain. Borrowing Ava Gardner from MGM, for instance, was a masterstroke of economy & opportunity, catapulting an underutilized actress to superstardom, while still getting her ‘on the cheap.’. Similarly, casting the untested & unknown Burt Lancaster in the male lead wouldn’t have been done on a larger studio picture, but as Burt admits “I was hired because I was the cheapest thing in town.” (Buford, p. 66). While the iconic pairing seems natural to modern viewers, it could have only happened in a low budget, independently produced film. As is often the case in looking back at classic films, chance sometimes plays as large a part in a film’s success as skill, planning and overt talent. Bringing Gardner & Lancaster together under the direction of Robert Siodmak was probably as impactful as Bogart & Bacall directed by Howard Hawks in To Have & Have Not (1944), which ironically was also based on Hemingway material. In both films, it’s a lightning strike connection between the couples that sets off the sexual and emotional connection that drives the films to greatness. It’s also the randomness of economy and sensibility that makes such connections happen in special films.

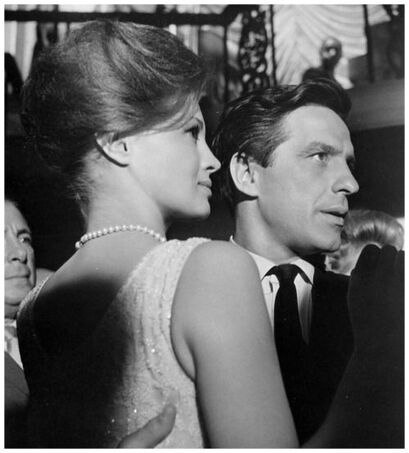

17 years later everything had changed. By the time Siegel went into production the Studio system was dead, killed off by shifting control of production from corporations to agents & stars, but also by the ever-increasing impact of television. As a made to TV production, Siegel’s version was also looking to produce the film on the cheap, & still hit upon 2 stars before they were famous. Sadly, they weren’t the romantic center of the film, but Lee Marvin (Charlie Strom) & Angie Dickinson (Sheila Farr) had as much an impact on the legacy of Sigel’s version as anything else in the production. Marvin’s killer, Strom, is the emotional center of the film. That he is a cold & cruelly emotionless cypher alters the film drastically, but it’s also what elevates the film to cult status. As the godfather of Tarantino’s hitmen in Pulp Fiction (1994), Marvin & sidekick Lee (Clu Gulager) trade witty, but meaningless banter, defusing the evil that they do. They elicit emotional empathy in the audience, even as they blandly kill, like punching a clock. Flat & emotionless is the way to describe the hitmen, but it also describes the central couple, which becomes the films greatest weakness. Later in the decade, both John Cassavettes (Johnny North) & Angie Dickinson (Farr) would achieve fame and respect as skilled actors, but here, as the fated couple, they aren’t allowed the chemical connection that would add the necessary weight to carry North to choose death over lost love. It’s artificial and flat, just like the rear projection screen as they race go-carts in the scene that supposed to build their love.

17 years later everything had changed. By the time Siegel went into production the Studio system was dead, killed off by shifting control of production from corporations to agents & stars, but also by the ever-increasing impact of television. As a made to TV production, Siegel’s version was also looking to produce the film on the cheap, & still hit upon 2 stars before they were famous. Sadly, they weren’t the romantic center of the film, but Lee Marvin (Charlie Strom) & Angie Dickinson (Sheila Farr) had as much an impact on the legacy of Sigel’s version as anything else in the production. Marvin’s killer, Strom, is the emotional center of the film. That he is a cold & cruelly emotionless cypher alters the film drastically, but it’s also what elevates the film to cult status. As the godfather of Tarantino’s hitmen in Pulp Fiction (1994), Marvin & sidekick Lee (Clu Gulager) trade witty, but meaningless banter, defusing the evil that they do. They elicit emotional empathy in the audience, even as they blandly kill, like punching a clock. Flat & emotionless is the way to describe the hitmen, but it also describes the central couple, which becomes the films greatest weakness. Later in the decade, both John Cassavettes (Johnny North) & Angie Dickinson (Farr) would achieve fame and respect as skilled actors, but here, as the fated couple, they aren’t allowed the chemical connection that would add the necessary weight to carry North to choose death over lost love. It’s artificial and flat, just like the rear projection screen as they race go-carts in the scene that supposed to build their love.

The final and most important distinction between the 2 films is in their respective style. Eddie Muller describes Siodmak’s camera movements as “ominous and elegant,” (Muller, p. 124) which perfectly lays out the basic & critical element in classic Film Noir. The camera placement, its angle & movement, as well as lighting, set design & composition of each shot are critical to establishing the mood and sensibility of Noir. Siodmak’s film is a master class in Film Noir style. As noted above, the opening scene establishes the verbal style of the film; tough, direct and purely expository, but also establishes the visual style that exacerbates the sense of doom that lingers throughout. Pools of light and dark shroud the killers as they cross an empty street to the well-lit diner; the light that spills across the Swede as the killers unleash a hail of bullets; and the lines of darkness that cross characters, bisecting them into pieces, all contribute to an unsettling mise en scene that keeps both the characters and the audience off balance. Even looking at individual characters within a frame helps to distinguish emotion, power and intentions. Gardner’s feline poses in several scenes, for instance, call to mind a cat teasing its prey into range by a casual nonchalance. Coiled danger cloaked in incredible beauty, all deliberately posed by Siodmak and his brilliant cinematographer Woody Bredell (Phantom Lady ’44). Siodmak, along with fellow German emigres Fritz Lang and Billy Wilder helped establish certain Film Noir codes, particularly expressionistic camera & lighting angles that are perfected here.

Siegel, who had worked steadily in television throughout the early 1960’s was poised to make a stylistically simpler film, given the fact his version was originally slated for tv. The inclusion of extreme violence, at least for tv in the 60’s, precluded the film from airing and it was instead given a theatrical release. It’s tv roots notwithstanding Siegel’s version reflects his very masculine and hard-edged sensibility as a director, showing what would become his trademark style in films like Dirty Harry (’71), Charlie Varrick (’73) & The Shootist (’76). Lack of sentimentality, square images, with little or very simple camera movement presents the films as its structure does, in a straightforward and uncomplicated way. The desaturated, washed out & brightly sunlit scenes leave little to the imagination and lack the depth of traditional Film Noir, which is not to condemn the film, but to cast it in light of what it was, a derivative of Noir, an anti-Noir. If Siegel set out to make something with Noir in mind, in subject matter and characterization, then he wildly succeeded, which is why his version is pointed to as a starting point for Neo-Noir. It is clear he accepted and understood the tenants of classic Noir, but stylistically he rejected them to find a different path, to create a different movement within in American film that would last far longer.

Siegel, who had worked steadily in television throughout the early 1960’s was poised to make a stylistically simpler film, given the fact his version was originally slated for tv. The inclusion of extreme violence, at least for tv in the 60’s, precluded the film from airing and it was instead given a theatrical release. It’s tv roots notwithstanding Siegel’s version reflects his very masculine and hard-edged sensibility as a director, showing what would become his trademark style in films like Dirty Harry (’71), Charlie Varrick (’73) & The Shootist (’76). Lack of sentimentality, square images, with little or very simple camera movement presents the films as its structure does, in a straightforward and uncomplicated way. The desaturated, washed out & brightly sunlit scenes leave little to the imagination and lack the depth of traditional Film Noir, which is not to condemn the film, but to cast it in light of what it was, a derivative of Noir, an anti-Noir. If Siegel set out to make something with Noir in mind, in subject matter and characterization, then he wildly succeeded, which is why his version is pointed to as a starting point for Neo-Noir. It is clear he accepted and understood the tenants of classic Noir, but stylistically he rejected them to find a different path, to create a different movement within in American film that would last far longer.

It’s unfair to compare these two films. They are literally alike in name only and represent two very distinct styles, stories and methods, but help to illustrate the overall differences between the classic Noir era and Neo-Noir. In some ways Neo-Noir can be seen as a rejection of the classic era, in other ways it pays homage and in still other ways it riffs on the ideas, the style and the implications of the film movement described by the French as Black Film!

Sources:

Detours and Lost Highways: A Map of Neo-Noir. Foster Hirsch. Limelight Editions. 1999.

Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir. Eddie Muller. 2021. Running Press.

Burt Lancaster: An American Life. Kate Buford. Alred A. Knopf. 2000.

Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style 3rd Ed. Ed. By Alain Silver & Elizabeth Ward. Overlook Press. 1992.

Sources:

Detours and Lost Highways: A Map of Neo-Noir. Foster Hirsch. Limelight Editions. 1999.

Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir. Eddie Muller. 2021. Running Press.

Burt Lancaster: An American Life. Kate Buford. Alred A. Knopf. 2000.

Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style 3rd Ed. Ed. By Alain Silver & Elizabeth Ward. Overlook Press. 1992.