The Noir Villainy of Dan Duryea

|

Prepared for The Great Villain Blogathon

Sponsoring site: Shadowsandsatin.com Direct Link: https://shadowsandsatin.wordpress.com/2019/05/24/the-great-villain-blogathon-2019 |

For a time in the mid to late 40’s, Dan Duryea was the go-to Noir villain who just happened to suck all the oxygen out of a room whenever he entered. In films like Scarlett Street (’45), The Woman in the Window (’44), Criss Cross (’49) & Too Late for Tears (’49) Duryea was a cool cad, always playing the angle & always willing to play rough when necessary. When he needed to ooze charm to seduce a lady his voice would change to a sweetness dripping with honey, but when he wanted to incite fear his voice could become shrill & sharp as a razor. It was a testament to Duryea’s abilities as an actor that both elements of his charters were believable & plainly clear why a woman could fall for him & why she would fear him. His characters were riveting to watch, with bits of business that made them fascinating & drew the viewer’s eye towards him in every scene. His lanky body & slicked back blonde hair produced the possibility of elegance, but his steely eyes, often narrowed to produce pure menace, undermined his normally high pitched & pleasant voice. He was the criminal the audience loved to hate; the devious slicker & the attention-grabbing presence felt throughout every film in which he appeared. Quite simply Dan Duryea was the magnetic center of Noir villainy around which dames, hooligans & innocent dupes orbited in a dance of often fatal inevitability.

Early in his career, in films like The Little Foxes (’41) & Ball of Fire (’41), Duryea made distinct impressions in smaller roles, but it was Fritz Lang’s Ministry of Fear (’44) that built upon those impressions & gave him his personae that resonated for the rest of the decade & beyond. Duryea, as a tailor/Nazi spy, plays a small role, but his casually threatening scene with star Ray Milland, in which he handles a pair of fabric shears, is the height of suspense and danger. Duryea’s offhand menace with the shears, as well as his sneering belligerence in his other significant scene, created the template for his characters for the next decade by drawing the viewers eyes to every bit of business & every word Duryea utters. While only on screen for a short time, and presumed dead for most of the film, Duryea’s Travers the Tailor leaves a distinct impression in the viewer & represents perhaps the greatest threat to Milland’s character. Duryea’s ability to make a lasting impression in a short amount of screen time, whether in Little Foxes or Ministry of Fear, would not only serve him well when he moved up to 3rd billing as he did in his next few roles, but also with an increased notoriety among fans & critics.

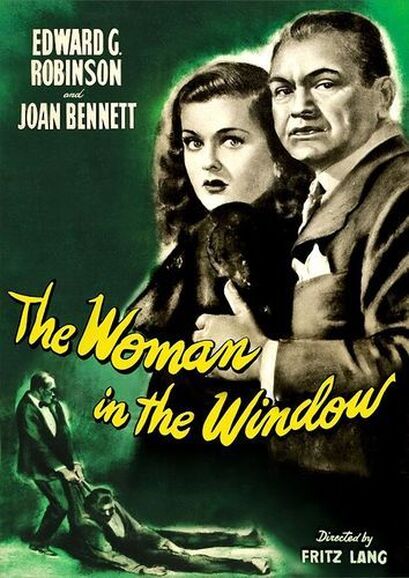

Duryea’s work on Ministry of Fear was noted by critics & audiences, but it was Lang’s next 2 films which solidified Duryea’s place in film history. In The Woman in the Window he blackmails a pair of accidental killers & in Scarlett Street he dupes a hapless bookkeeper, while bullying his duplicitous girlfriend. Both movies feature Duryea, along with Edward G. Robinson & Joan Bennett & the success of the first led to the immediate production of the second. In both films Duryea presents the rare combination of danger & likability, which made him appealing to both male & female viewers. It’s believable that he could seduce a woman, while at the same time throw off a violent & frightening vibe.

Duryea’s work on Ministry of Fear was noted by critics & audiences, but it was Lang’s next 2 films which solidified Duryea’s place in film history. In The Woman in the Window he blackmails a pair of accidental killers & in Scarlett Street he dupes a hapless bookkeeper, while bullying his duplicitous girlfriend. Both movies feature Duryea, along with Edward G. Robinson & Joan Bennett & the success of the first led to the immediate production of the second. In both films Duryea presents the rare combination of danger & likability, which made him appealing to both male & female viewers. It’s believable that he could seduce a woman, while at the same time throw off a violent & frightening vibe.

The Woman in the Window has a dull professor, played against type by Robinson, bewitched by the painted image of a woman in a shop window. When he meets her, shares drinks & returns to her apartment it sets off a chain of events that leads to murder and the couple vainly attempting to cover it up. In typical noir fashion there are steps to take to dispose of the body, clean the crime scene & dissolve the relationship, such that it is, between the killers. Unfortunately, once the dead man is established as missing, his bodyguard (Duryea) figures the woman (Bennett) has something to do it. In a scene that is one of Noir’s best, Duryea forces his way into Bennett’s apartment claiming to be a cop, intimidating her while he moves about the apartment going through drawers, closets & boxes. His voice conveys a knowing & threatening tone, attempting to corner her in a slip of the tongue. Even his voice, heard over the intercom, before he has even entered the building’ sets the tone for his performance, when he threatens, “You don’t want me to get tough, do you?” The reading of the line, with the emphasis on “tough” immediately signals that he’d be none too happy to do just that if necessary or properly prompted.

Duryea’s appearance, more than an hour into the film, signals a change in tone & ramps up the stakes by destroying the couple’s plans & creating a triangle between the couple, the cops/DA & Duryea’s blackmailer. Because Robinson’s character is friends with the DA there is an unlikely balance between the criminals, the law & the outlaw, that ratchets up the suspense while it squeezes the couple from both sides. Duryea’s second masterful scene takes place after the couple has decided to poison him & Bennett is tasked with seductively lulling him into drinking poison. His opening line, again dripping with a mix of danger & charm, sets the tone for the punch & counter punch of the seduction/murder attempt, when he says “If that’s for me, I like it!” in response to her seductive outfit. When he eventually begins to soften to her charms, accepting the drink that would kill him, he menacingly fills the doorway as she makes it, wanting to trust her, but instinctively knowing not to. Her charms further soften him and the physical change in Duryea is noticeable, his voice changes to a softer register & his cadence slows when he practically purrs “I’m not such a bad guy.” The performance almost makes the viewer believe for a moment that he could be, but he quickly snaps out of it, realizes the drink is her focus & briskly snaps “it’s all settled then, is it?”, then “I thought so,” as he backhands her across the face. “You amateurs” he then spits & demands $5,000 more, making it perfectly clear that he is on to her seduction. The range of emotion & the physical & vocal changes are perfect Duryea, presenting succinctly the breadth & depth of his acting chops & his appeal to men & women…he is dangerous, but if you can solve the riddle he could be sweet & soft.

Duryea’s appearance, more than an hour into the film, signals a change in tone & ramps up the stakes by destroying the couple’s plans & creating a triangle between the couple, the cops/DA & Duryea’s blackmailer. Because Robinson’s character is friends with the DA there is an unlikely balance between the criminals, the law & the outlaw, that ratchets up the suspense while it squeezes the couple from both sides. Duryea’s second masterful scene takes place after the couple has decided to poison him & Bennett is tasked with seductively lulling him into drinking poison. His opening line, again dripping with a mix of danger & charm, sets the tone for the punch & counter punch of the seduction/murder attempt, when he says “If that’s for me, I like it!” in response to her seductive outfit. When he eventually begins to soften to her charms, accepting the drink that would kill him, he menacingly fills the doorway as she makes it, wanting to trust her, but instinctively knowing not to. Her charms further soften him and the physical change in Duryea is noticeable, his voice changes to a softer register & his cadence slows when he practically purrs “I’m not such a bad guy.” The performance almost makes the viewer believe for a moment that he could be, but he quickly snaps out of it, realizes the drink is her focus & briskly snaps “it’s all settled then, is it?”, then “I thought so,” as he backhands her across the face. “You amateurs” he then spits & demands $5,000 more, making it perfectly clear that he is on to her seduction. The range of emotion & the physical & vocal changes are perfect Duryea, presenting succinctly the breadth & depth of his acting chops & his appeal to men & women…he is dangerous, but if you can solve the riddle he could be sweet & soft.

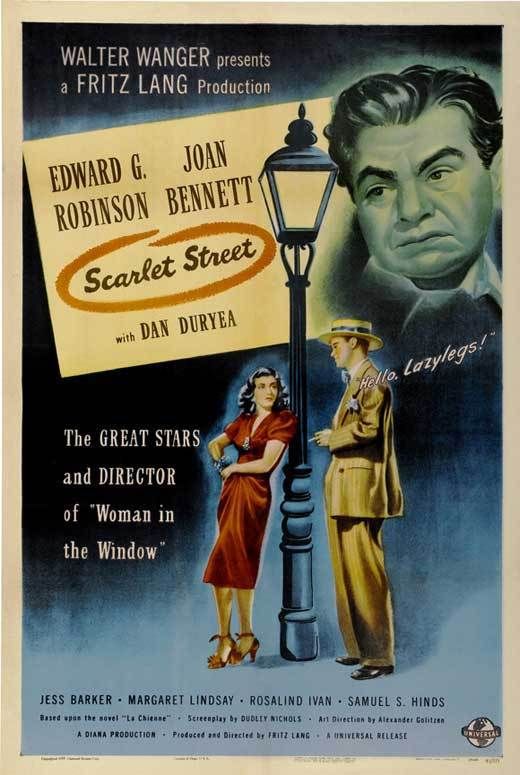

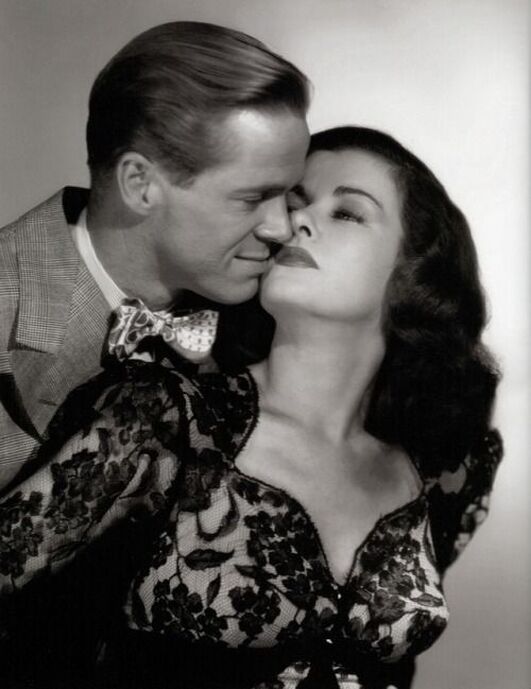

Taking this dichotomy one step further is Scarlett Street, where Duryea & Bennet are already a couple when the story begins, but he is no sweeter & offers up a much higher dose of menace, bordering on sadism. Whereas in The Woman in the Window, where we are introduced to Duryea’s character as a voice over an intercom, in Scarlett Street he is first seen smacking Bennett around on a street corner. It’s as if Scarlett Street ignored the outcome of the prior film and moved right into an alternate reality of Bennett & Duryea actually consummating the give & take of their final violent dance from Woman in the Window. Coming to Bennet’s rescue is brow-beaten & milquetoast bookkeeper Christopher Cross (Robinson), who chases Duryea off with a few deft swipes of his umbrella. What transpires over the next hour & 30 minutes is a deft combination of Noir intrigue, a twisted love triangle, built on dual masochistic foundations, & a film that dances along a tightwire of Production Code violations.

Bennett’s & Duryea’s relationship is made clear in the scene noted above, but as the film transpires it becomes evident that it is far more twisted than mere physical abuse. In a manner that was only partially censored by the Production Code Administration, their relationship is clearly built on Johnny satisfying Kitty sexually. This is made evident in the following exchanges, the first allowed by censors & the second eliminated (Peros, p. 45):

Kitty: “I don’t know why I’m so crazy about you.”

Johnny: “Oh, yes you do!”

Kitty: “Can’t you do any better than that?”

Johnny: “That’s all you ever think about, Lazy Legs.”

Kitty: “What else is there to think about?”

Kitty’s purring happiness the morning after Johhny sleeps over further reinforces the sexual nature of their relationship, while their verbal interaction makes it clear that this is largely a one-sided infatuation. Peros also notes that “Duryea’s Johnny is vicious & exploitive, yet he also displays enough sheer magnetism to convey what attracts Kitty to him.” This is the essence of Duryea’s performances in Film Noir after Film Noir, distilled in Johnny’s disdainful exploitation of Kitty.

Once Chris becomes smitten with Kitty, who has mistaken him for a wealthy artist, Johnny has no problem forcing Kitty into a relationship with him, telling her “Baby, you got him on the hook & he can’t get off you. You got him softened up.” Johnny’s only interest is in the score. He’s not apologetic when he hurts Kitty, in fact he only refrains from hitting her by claiming “if I wasn’t a gentleman” as his hand rears back, but it’s clear he has hit her before. Duryea once again manipulates his voice to convey disgust & pure vitriol one moment, while sliding into manipulative sweet talk in the next. Johnny’s manic rush to exploit Chris, at the cost of his relationship with Kitty, allows Duryea to emphasize the coolly calculating nature of Johnny by having him manipulate everyone in his path, revealing the true character that Kitty cannot see.

Scarlett Street, perhaps unlike any other film of the Production Code era, allowed the murderer to walk free, albeit justified by mental illness, while punishing an evil man for crimes he didn’t commit. Duryea’s behavior in all 3 of the Lang films allows for such a conclusion because the viewer would have generally shrugged at his character’s outcome. He’s earned that disdain or indifference, but it’s still a surprising conclusion in such a tightly controlled era.

Bennett’s & Duryea’s relationship is made clear in the scene noted above, but as the film transpires it becomes evident that it is far more twisted than mere physical abuse. In a manner that was only partially censored by the Production Code Administration, their relationship is clearly built on Johnny satisfying Kitty sexually. This is made evident in the following exchanges, the first allowed by censors & the second eliminated (Peros, p. 45):

Kitty: “I don’t know why I’m so crazy about you.”

Johnny: “Oh, yes you do!”

Kitty: “Can’t you do any better than that?”

Johnny: “That’s all you ever think about, Lazy Legs.”

Kitty: “What else is there to think about?”

Kitty’s purring happiness the morning after Johhny sleeps over further reinforces the sexual nature of their relationship, while their verbal interaction makes it clear that this is largely a one-sided infatuation. Peros also notes that “Duryea’s Johnny is vicious & exploitive, yet he also displays enough sheer magnetism to convey what attracts Kitty to him.” This is the essence of Duryea’s performances in Film Noir after Film Noir, distilled in Johnny’s disdainful exploitation of Kitty.

Once Chris becomes smitten with Kitty, who has mistaken him for a wealthy artist, Johnny has no problem forcing Kitty into a relationship with him, telling her “Baby, you got him on the hook & he can’t get off you. You got him softened up.” Johnny’s only interest is in the score. He’s not apologetic when he hurts Kitty, in fact he only refrains from hitting her by claiming “if I wasn’t a gentleman” as his hand rears back, but it’s clear he has hit her before. Duryea once again manipulates his voice to convey disgust & pure vitriol one moment, while sliding into manipulative sweet talk in the next. Johnny’s manic rush to exploit Chris, at the cost of his relationship with Kitty, allows Duryea to emphasize the coolly calculating nature of Johnny by having him manipulate everyone in his path, revealing the true character that Kitty cannot see.

Scarlett Street, perhaps unlike any other film of the Production Code era, allowed the murderer to walk free, albeit justified by mental illness, while punishing an evil man for crimes he didn’t commit. Duryea’s behavior in all 3 of the Lang films allows for such a conclusion because the viewer would have generally shrugged at his character’s outcome. He’s earned that disdain or indifference, but it’s still a surprising conclusion in such a tightly controlled era.

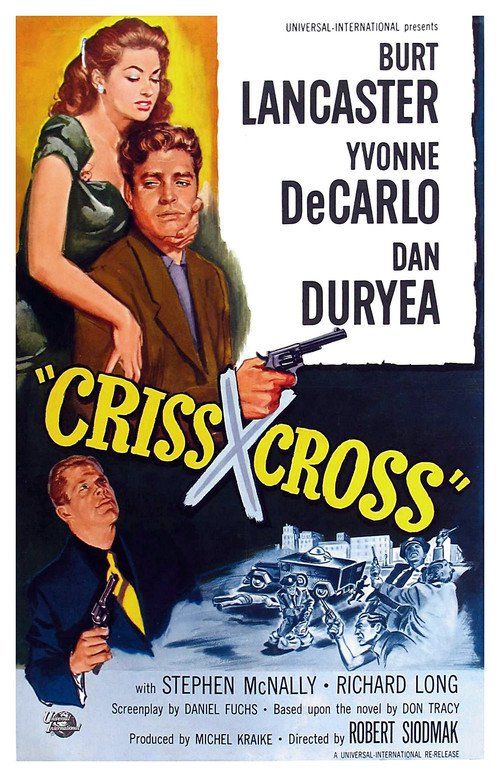

Criss Cross (’49), Robert Siodmak’s Noir classic, has Duryea at his despicable best, but in this case he has married the women he loves & exploits. In typical Duryea fashion his character’s introduction sets the tone for his entire performance. His Slim Dundee menacingly questions Anna (Yvonne DeCarlo) just after she has returned from a rendezvous with former husband/patsy Steve (Burt Lancaster). Both his physical presence & his accusatory voice make it clear that Dundee is a far more dangerous character than any he played in the Lang films. While Johnny may have hit his woman, Dundee has clearly killed before & inspires fear among all those around him. His charisma, however, also clearly draws those around him into his sphere. Criss Cross exploits the totality of Duryea’s Noir performances by polishing up his dripping charm, while at the same time sharpening his malevolent evil. & violent nature. Told primarily in flashback, and focusing primarily on Steve & Anna’s dysfunctional, yet passionate relationship, Criss Cross is like a rock (Lancaster) rolling downhill on its way to crashing into the ocean; the inevitability is obvious, but the speed is intoxicating. Dundee clearly rules over Anna through fear, but just like Kitty in Scarlett Street, there is a sexual power undertone. She is his possession. The scene when Dundee discovers Steve & Anna together is one of high suspense, punctuated by Duryea’s crisp & accusatory questioning of Steve. “This don’t look right, you can’t tell me this looks right. You want to see me? What business could we possibly have, Steve?” Duryea’s reading is a perfect mix of skepticism, accusation & threat. He knows what he knows & he’s forcing Steve to confess of create a plausible falsehood. Duryea/Dundee practically makes the room shrink in around Steve until he blurts out his improvised plan for the heist, which only partially placates Dundee. Duryea again coolly switches the tone of his performance, just as he did with Kitty in Scarlett Street & Alice in The Woman in the Window, from dangerous to conciliatory. He wants Steve to keep digging his own grave, so to speak, as he outlines the heist, while Dundee skepticly prods him. Dundee knows what he knows, just as with Kitty, but his greed/desire allows Steve & the plan to run its course. Dundee’s final scene in the film, in which he emerges from the darkness like a spectre, places the perfect exclamation point on Duryea’s greatest Noir performance. His final act as executioner stamps him as the ultimate force of nature, perfectly capable of destroying everyone before him.

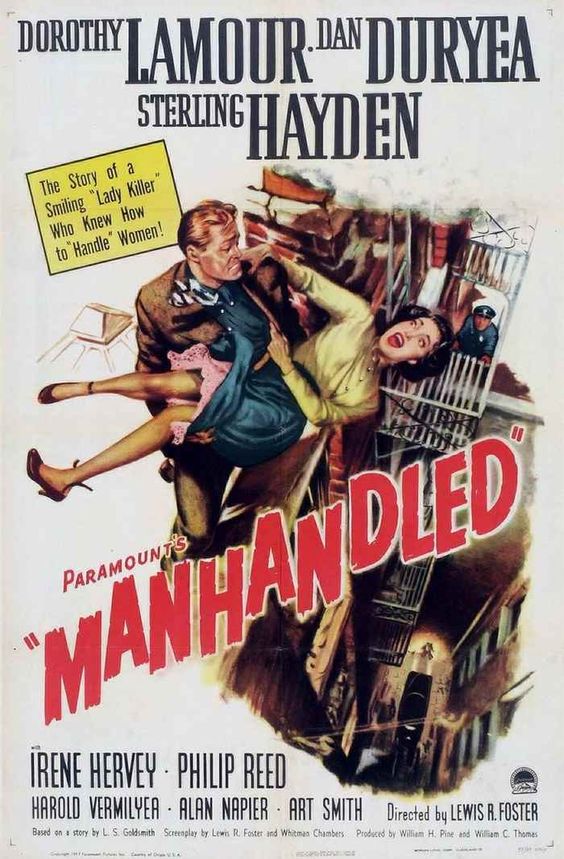

Duryea’s Noir legacy extended to some 18 films, but these 3 distilled & perfected the performances that made him an icon of slick malevolence. He was charm & smarm in one lanky & cool customer. In films like Too Late for Tears (’49), Manhandled (’49), Black Angel (’46) & The Underworld Story (’50) there were pieces of Johnny, Slim & Heidt in each of his performances, the charm, the danger, the manipulation & the exploitation. Duryea was a master at Noir villainy and he stands alone as the quintessential seductive/destructive charmer, capable of syrupy sweet talk & ice cold threats in the blink of an eye!

Sources:

Dan Duryea: Heel with a Heart. Mike Peros. University Press of Mississippi. 2016

Noir City Magazine Volume 8, No. 2. Fall 2013. Film Noir Foundation.

Sources:

Dan Duryea: Heel with a Heart. Mike Peros. University Press of Mississippi. 2016

Noir City Magazine Volume 8, No. 2. Fall 2013. Film Noir Foundation.