Plot:

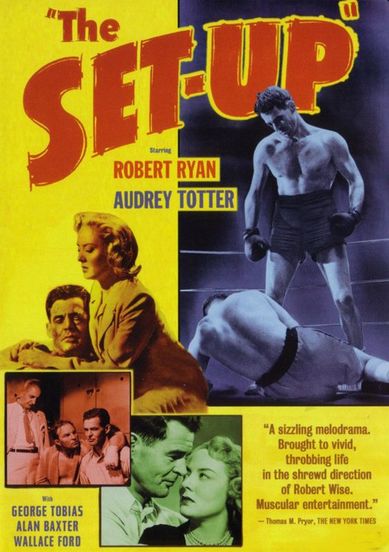

Stoker Thompson (Ryan) is a middling heavyweight boxer on the down side of his career, looking for one more payday in a fight with a young up & comer. Unfortunately, unbeknownst to him, his manager Tiny (Tobias) has agreed to throw the fight to pad the pockets of mobster Little Boy (Baxter). Taking place in real time (a taut 72 minutes), Thompson prepares for the fight, against the better wishes of his wife Julie (Totter) who decides not to attend, fearing the worst & telling Stoker “you’re always just one punch away” in reply to his dreams of a title fight. When Stoker finds out the fix is in he goes all out to defeat the younger fighter, but must answer to Little Boy when he knocks the kid out.

Stoker Thompson (Ryan) is a middling heavyweight boxer on the down side of his career, looking for one more payday in a fight with a young up & comer. Unfortunately, unbeknownst to him, his manager Tiny (Tobias) has agreed to throw the fight to pad the pockets of mobster Little Boy (Baxter). Taking place in real time (a taut 72 minutes), Thompson prepares for the fight, against the better wishes of his wife Julie (Totter) who decides not to attend, fearing the worst & telling Stoker “you’re always just one punch away” in reply to his dreams of a title fight. When Stoker finds out the fix is in he goes all out to defeat the younger fighter, but must answer to Little Boy when he knocks the kid out.

Thoughts:

The Set-Up boils Noir down to its essence, in that the ideas of fatalism, self-determination & corruption arc throughout Art Cohn’s script, Milton Krasner’s camera work & Robert Wise’s direction. The opening scene, in fact, is a microcosm of all three as the camera swivels & moves, following different people as they paint the picture of the world of Paradise City and the boxing sub-culture, including the aggressive young paperboy taking business from the addled former boxing trying to sell score sheets, the aggressive fans looking for blood to be spilled & Thompson’s own crooked manager confirming the fix, taking the cash, then shorting his partner on the take. It’s a carnivorous world of dog eat dog, with the good, slow or innocent swallowed up whole.

Stoker just wants to fight and Julie just wants him to quit. When she tells him she won’t watch him get “his head bashed in” anymore Stoker still holds out hope she will change her mind, continually looking out from the locker room window towards her hotel room window, then to the seat he has reserved for her. Wise does nicely to frame the hotel through a triangular opening in the window diagonally splitting Stokers life between boxing & his wife. He also frames Julie’s empty seat between the ropes, as if reinforcing the division in Stoker’s life. Krasner/Wide further uses the ring to separate what is moral and what is immoral by darkening the arena around it to make it appear to be floating in darkness protecting Stoker from the double cross of his manager & the venality of Little Boy and the other crass patrons who cheer for Stoker’s demise. Stoker’s desire for victory within the ring, is pure, although entirely misguided. It’s all he knows and it keeps him innocent, if not completely ignorant of the corruption around him. Even when he discovers the double cross he fights not just for principle, but for some kind of salvation, albeit violently at the hands of Little Boy and his henchmen.

Art Cohn’s script is spun tight, with little, if any, wasted words or action. He wonderfully paints the arc of the boxer’s life in the expectations of each boxer before & after they have their fight. The young fighters full of expectations, the rising stars confident, and the old punchers completely delusional; all watched carefully by Stoker, secure in his understanding of the arc, but mistaken in his ultimate place within the arc. Cohn’s script foreshadows Stoker’s fall, but is careful not to telegraph it, resting in the oppressive nature of the corruption to push the story to its conclusion. Only in the redemptive positioning of Julie, framed at the beginning of the movie in the hotel room and at the end on the sidewalk, lifts The Set-Up from its emersion in Noir cynicism. As noted the run time of the movie, 72 minutes happens in real time, a testament to the sharpness of the production.

Ryan’s performance, however, is the sun that the movie revolves around and his portrayal of Stoker as a noble beast is the best of his stellar career. Ryan was always a subtle and reserved actor, often paring down his performances to as minimalistic as possible, quite often, as here, performed with a quiet dignity. My favorite scenes are in the locker room as the different boxers shuffle through, sharing their expectations and concerns on the way to the ring & their disappointments or triumphs upon their return. Ryan calmly & quietly observes the fighters, offering small encouragements, but it’s his eyes that tell the stories that are reeling in his head. They glimmer as he recalls a satisfying memory and burn darkly when he sees a dark future. Ryan is such a subtle actor that reaction shots are all that are needed to expand the story and fill in missing and unnecessary dialogue. His resignation of his fate after winning the fight is also a master class in subtlety. As he first tries to escape through the arena he appears like a caged animal thrashing about, but once he’s in the alley defending himself he’s a cornered animal with just his eyes reflecting his self-defense plan.

The Set-Up boils Noir down to its essence, in that the ideas of fatalism, self-determination & corruption arc throughout Art Cohn’s script, Milton Krasner’s camera work & Robert Wise’s direction. The opening scene, in fact, is a microcosm of all three as the camera swivels & moves, following different people as they paint the picture of the world of Paradise City and the boxing sub-culture, including the aggressive young paperboy taking business from the addled former boxing trying to sell score sheets, the aggressive fans looking for blood to be spilled & Thompson’s own crooked manager confirming the fix, taking the cash, then shorting his partner on the take. It’s a carnivorous world of dog eat dog, with the good, slow or innocent swallowed up whole.

Stoker just wants to fight and Julie just wants him to quit. When she tells him she won’t watch him get “his head bashed in” anymore Stoker still holds out hope she will change her mind, continually looking out from the locker room window towards her hotel room window, then to the seat he has reserved for her. Wise does nicely to frame the hotel through a triangular opening in the window diagonally splitting Stokers life between boxing & his wife. He also frames Julie’s empty seat between the ropes, as if reinforcing the division in Stoker’s life. Krasner/Wide further uses the ring to separate what is moral and what is immoral by darkening the arena around it to make it appear to be floating in darkness protecting Stoker from the double cross of his manager & the venality of Little Boy and the other crass patrons who cheer for Stoker’s demise. Stoker’s desire for victory within the ring, is pure, although entirely misguided. It’s all he knows and it keeps him innocent, if not completely ignorant of the corruption around him. Even when he discovers the double cross he fights not just for principle, but for some kind of salvation, albeit violently at the hands of Little Boy and his henchmen.

Art Cohn’s script is spun tight, with little, if any, wasted words or action. He wonderfully paints the arc of the boxer’s life in the expectations of each boxer before & after they have their fight. The young fighters full of expectations, the rising stars confident, and the old punchers completely delusional; all watched carefully by Stoker, secure in his understanding of the arc, but mistaken in his ultimate place within the arc. Cohn’s script foreshadows Stoker’s fall, but is careful not to telegraph it, resting in the oppressive nature of the corruption to push the story to its conclusion. Only in the redemptive positioning of Julie, framed at the beginning of the movie in the hotel room and at the end on the sidewalk, lifts The Set-Up from its emersion in Noir cynicism. As noted the run time of the movie, 72 minutes happens in real time, a testament to the sharpness of the production.

Ryan’s performance, however, is the sun that the movie revolves around and his portrayal of Stoker as a noble beast is the best of his stellar career. Ryan was always a subtle and reserved actor, often paring down his performances to as minimalistic as possible, quite often, as here, performed with a quiet dignity. My favorite scenes are in the locker room as the different boxers shuffle through, sharing their expectations and concerns on the way to the ring & their disappointments or triumphs upon their return. Ryan calmly & quietly observes the fighters, offering small encouragements, but it’s his eyes that tell the stories that are reeling in his head. They glimmer as he recalls a satisfying memory and burn darkly when he sees a dark future. Ryan is such a subtle actor that reaction shots are all that are needed to expand the story and fill in missing and unnecessary dialogue. His resignation of his fate after winning the fight is also a master class in subtlety. As he first tries to escape through the arena he appears like a caged animal thrashing about, but once he’s in the alley defending himself he’s a cornered animal with just his eyes reflecting his self-defense plan.

Category: Film Noir

See Also: Crossfire (’47), Champion (’49), The Racket (’51), Raging Bull (’80)

Random Notes & Quotes:

*Robert Ryan was a championship boxer as an undergrad at Dartmouth.

*Robert Wise also directed The Sound of Music (’65), West Side Story (’61) & Star Trek: The Movie (’79) in a career that spanned 50+ years, beginning as an editor in 1939. While often overlooked on lists of the greatest American directors, he won 2 Academy Awards for best Director (Sound of Music & West Side Story).

*Wise also edited Citizen Kane (’42), receiving an Academy Award nomination (losing to William Holmes for Sergeant York ‘42).

*Martin Scorsese often credits the boxing sequences of The Set-Up as having a primary influence on how he shot Raging Bull (’80).

See Also: Crossfire (’47), Champion (’49), The Racket (’51), Raging Bull (’80)

Random Notes & Quotes:

*Robert Ryan was a championship boxer as an undergrad at Dartmouth.

*Robert Wise also directed The Sound of Music (’65), West Side Story (’61) & Star Trek: The Movie (’79) in a career that spanned 50+ years, beginning as an editor in 1939. While often overlooked on lists of the greatest American directors, he won 2 Academy Awards for best Director (Sound of Music & West Side Story).

*Wise also edited Citizen Kane (’42), receiving an Academy Award nomination (losing to William Holmes for Sergeant York ‘42).

*Martin Scorsese often credits the boxing sequences of The Set-Up as having a primary influence on how he shot Raging Bull (’80).