The Films of Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

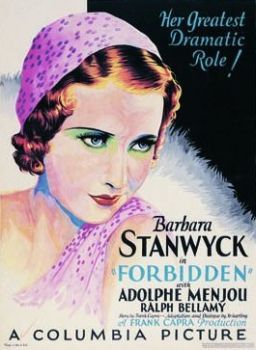

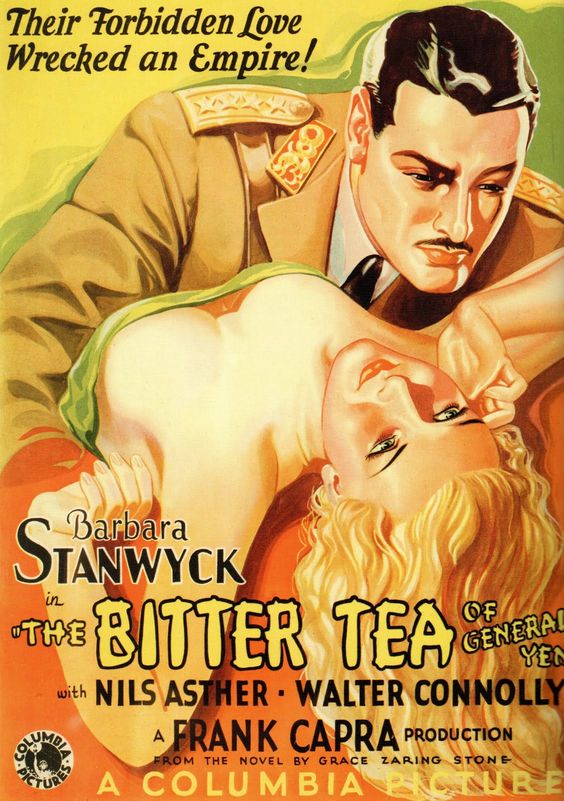

Frank Capra’s love for Barbara Stanwyck furthered both of their careers, added some fine films to history & created an interesting arc of a blurred person/professional relationship. Beginning with Ladies of Leisure (’30), that reflected the initial stages of infatuation, through The Miracle Woman (’31) and it’s idealization of love, to Forbidden (’32) and the last gasp at self sacrificing romantic love, then The Bitter Tea of General Yen’s (’32) fetishization of love & finally, years later with Meet John Doe (’40) & the resignation that the relationship is over & the lovers are who they are, their movies reflected Capra’s desire for one his most important leading ladies. Together, Capra & Stanwyck made 5 films spanning 11 years, that compared to the length of their respective careers is rather minor, but they imprinted a style on each other that served them well throughout their careers. That they made the films together while Capra harbored an evolving range of romantic emotions towards Stanwyck is a testament to their professionalism and serves as a time capsule of the arc of their relationship.

While they began working together after he was a well-established filmmaker (and the bell of the Columbia Pictures lot), Stanwyck came to their first film together, Ladies of Leisure (’30), as a stage trained film novice with only 2 screen credits to her name. Her first 2 film experiences had been less than enjoyable & she was dismayed by the fakeness that she saw in every corner of Hollywood. She was foisted on Capra by Columbia Pictures boss Harry Cohn, however, who believed she wasn’t pretty enough for movies, but wanted to try her out. Their first meeting was a disaster, with Stanwyck offering monosyllabic answers, then storming out of the room with nothing but a “You don’t want any part of me” parting comment. Capra immediately called Cohn, called Stanwyck nothing but a porcupine and dropped the matter, ready to turn to the actress he initially wanted for the part. Stanwyck’s husband, self-proclaimed ‘king of vaudville’ Frank Fay, begged him to watch a screen test Stanwyck had shot with Alexander Korda, who would go on to produce The Scarlett Pimpernel (’34) & The Third Man (’49), among many other classics in England. Capra agreed & was moved to tears as he watched Stanwyck perform a scene from “The Noose”, a play she had appeared nearly 200 shows in New York. Stanwyck was cast.

While they began working together after he was a well-established filmmaker (and the bell of the Columbia Pictures lot), Stanwyck came to their first film together, Ladies of Leisure (’30), as a stage trained film novice with only 2 screen credits to her name. Her first 2 film experiences had been less than enjoyable & she was dismayed by the fakeness that she saw in every corner of Hollywood. She was foisted on Capra by Columbia Pictures boss Harry Cohn, however, who believed she wasn’t pretty enough for movies, but wanted to try her out. Their first meeting was a disaster, with Stanwyck offering monosyllabic answers, then storming out of the room with nothing but a “You don’t want any part of me” parting comment. Capra immediately called Cohn, called Stanwyck nothing but a porcupine and dropped the matter, ready to turn to the actress he initially wanted for the part. Stanwyck’s husband, self-proclaimed ‘king of vaudville’ Frank Fay, begged him to watch a screen test Stanwyck had shot with Alexander Korda, who would go on to produce The Scarlett Pimpernel (’34) & The Third Man (’49), among many other classics in England. Capra agreed & was moved to tears as he watched Stanwyck perform a scene from “The Noose”, a play she had appeared nearly 200 shows in New York. Stanwyck was cast.

When shooting began, Capra immediately realized that Stanwyck’s first take were always her strongest and she tended to fade with each successive redo. He attributed it to her stage training, but took it to heart, rehearsing the other actors, but never Stanwyck. In a move that would elicit an intimacy between them, Capra would come to her dressing room and quietly explain to Stanwyck what he wanted for each scene. He would then shoot the scene in reverse sequence, ie close-ups first, then medium shots & finally establishing shots, which was the opposite of common Hollywood practice. Ladies of Leisure is based on a failed play called “Ladies of the Evening” from 1924 and tells the story of ‘party girl’/prostitute Kay Arnold as she meets and falls in love with an idealist painter. That Kay & Barbara had troubled backstories, Barbara’s filled with the death and abandonment of her parents & subsequent foster homes, allowed Barbara to treat Kay as an offshoot of her own life, which is what Capra wanted to force from his leading lady: that she act naturally. One line in the screenplay is particularly telling & could have been said by Capra to Stanwyck, instead of by the painter (Ralph Graves) to Kay: “I can’t paint you if I can’t see you.” He then removes her makeup, but at the same time signals that the artiface of Kay’s/Barbara’s performance needs to be stripped away. That line and the associated image is as intimate a moment as there is in the film & shows the tenderness that the director had towards his leading lady. Later, Capra choreographs what Stanwyck biographer Dan Callahan calls one of Stanwyck’s great performance ‘arias’ in a scene with only a rainstorm & a crackling fire for sound. In it, Kay lays uncomfortably on a couch in the artist’s apartment, longing for him to come take her, but fearing she’d become what she’s tried to escape, a piece of meat meant for male conquest. Capra captures Stanwyck in close ups, allowing her eyebrows, her mouth & her eyes to convey her wide range of emotions. As the artist opens the door and moves towards her, the combination of wonting and revulsion is palatable and speaks to the depths of Stanwyck’s abilities so early in her career. When he merely places another blanket on her, the relief and joy in her expression is moving. Capra has visually & aurally simplified this scene to its essence & captures such intimacy in Stanwyck’s performance that it’s impossible to not see his love through the camera.

After filming was finished Capra knew he had captured something special on film and would elevate Stanwyck from a featured player to a star. At the time he was single & Capra biographer Jospeh McBride surmises that the two began an on again/off again 2 & a half year affair & bolsters his claim with this quote from Capra:

“It is true that all directors fall in love with their leading ladies-at least while making a film together. They come to know each other so intimately-more so than some married couples-and their relationship is so close emotionally, so charged creatively, it can easily drift in a Pygmalion & Galatea affinity. I fell in love with Barbara Stanwyck, and had I not been more in love with Lucille Reyburn (Capra’s soon to be 2nd wife) I would have asked her to marry me after she called it quits with Frank Fay (Barbara’s husband at the time). P. 216.

Ladies of Leisure would be prelude, the early infatuation with his star that may or may not have been reciprocated. He was aware of what Stanwyck brought to the table, however, & it gave him both physical and emotional joy. He was smitten

After filming was finished Capra knew he had captured something special on film and would elevate Stanwyck from a featured player to a star. At the time he was single & Capra biographer Jospeh McBride surmises that the two began an on again/off again 2 & a half year affair & bolsters his claim with this quote from Capra:

“It is true that all directors fall in love with their leading ladies-at least while making a film together. They come to know each other so intimately-more so than some married couples-and their relationship is so close emotionally, so charged creatively, it can easily drift in a Pygmalion & Galatea affinity. I fell in love with Barbara Stanwyck, and had I not been more in love with Lucille Reyburn (Capra’s soon to be 2nd wife) I would have asked her to marry me after she called it quits with Frank Fay (Barbara’s husband at the time). P. 216.

Ladies of Leisure would be prelude, the early infatuation with his star that may or may not have been reciprocated. He was aware of what Stanwyck brought to the table, however, & it gave him both physical and emotional joy. He was smitten

The pair’s second feature together, The Miracle Woman (’31), brought a more mature reflection of their relationship, albeit one that gilds the lily by copping out on the real intention of the story. Based on a satirical play by John Meehan called “Bless You Sister”, calling out religious fakes, particularly Amy Semple McPherson types, Capra & screenwriter Jo Swerling tempered Stanwyck’s Florence Fallon character’s cynicism and revenge & instead placed it on her manager, Hornsby. Capra later noted that this was his greatest regret about The Miracle Woman, but it’s easy to see his choice was dictated by his feelings for Stanwyck. Stanwyck opens the film in her father’s church as she approaches the pulpit to deliver his final sermon. As she begins, she is the picture of forthrightness and calm, but as the real story of betrayal and disappointment becomes clear Stanwyck/Florence moves from controlled anger, to anguished resentment & finally to accusatory rage. In the span of a few minutes Stanwyck’s performance goes from zero to 60 and builds in a realistic and natural way. As Callahan writes, “The Miracle Woman is an unforgettable first scene in search of a movie to follow it.” (p. 26). Unforgettable it is, but the rest of the film is still quite strong. When huckster Hornsby mockingly claps his hands in the now empty church and outlines a means for revenge, “Get Famous. Get Rich. Get Even”, even the angelic Florence buys into the idea. Again, because Capra shifted the exploitation of worshipers from Florance to Hornsby as the ministry grows it is Florence who must wrestle with her conscience, looking for redemption. A telling scene, and reflecting back to Ladies of Leisure, has Florence violently removing her makeup backstage after a particularly gut-wrenching performance. She is once again stripping off her mask to show her true self, just as Capra wished in the first film. Here, however, he mask is one of a true believer, who must work honestly to achieve salvation, something she’s not able to do with Hornsby planted shills always looking for attention. Once blind former pilot John Carson is ‘saved’ by her voice over the radio & comes to Florence’s revival, she has the focus for redemption & salvation that Capra holds her up for.

For added emphasis, Capra counterbalances the chaos & underhandedness at the tabernacle with the peace & serenity in Carson’s apartment. While he is blind, he can still ‘see’ her for what she truly is. Capra is asking the audience to do the same, elevating her image, her character & Stanwyck herself to purity. As is Capra’s wont, he even places the exclamation point on her redemption through fire, purifying her literally as the tabernacle burns. Florence/Stanwyck is placed on the pedestal of pure love when she is finally shown as a servant in the Salvation Army, cleansed of her mask, vengeance & hatred & redeemed as only an idealized love could be.

For added emphasis, Capra counterbalances the chaos & underhandedness at the tabernacle with the peace & serenity in Carson’s apartment. While he is blind, he can still ‘see’ her for what she truly is. Capra is asking the audience to do the same, elevating her image, her character & Stanwyck herself to purity. As is Capra’s wont, he even places the exclamation point on her redemption through fire, purifying her literally as the tabernacle burns. Florence/Stanwyck is placed on the pedestal of pure love when she is finally shown as a servant in the Salvation Army, cleansed of her mask, vengeance & hatred & redeemed as only an idealized love could be.

With Forbidden (’32) Capra proclaims his last gasp of achieving real, self-sacrificing love with Stanwyck by having her character actually become a martyr for love. Stanwyck is a staid & dependable librarian when the film opens, the opposite of the party girl in Ladies of Leisure & without the resentment in The Miracle Woman. She is good and wholesome, the perfect woman to be a wife and mother, but she decides to embark on a vacation to Havana to find romance. At first all seems fine when she meets & falls in love with a mysterious lawyer, Grover, (Adolphe Menjou) who sweeps her off her feet and romances her, complete with masks for a masquerades party. Once again, Stanwyck’s character must strip herself of a mask to free her true self, but this time her lover is masked more successfully. When she becomes pregnant and it is clear the lawyer is not who he says he is, she retreats, not behind a mask or disguise, but towards her true self, a self-sacrificing mother, willing to raise the child on her own. She is the dream woman of Capra’s fantasies, loyal to a fault & ready to give up everything to create a family that she will nurture and protect. She even loves a married man (Capra) without asking him to sacrifice his life for her love.

What Capra & screenwriter Jo Swerling (from Capra’s story) do is bring a little of real life into the story by peppering in elements of both Stanwyck’s husband, Frank Fay, (whom Capra did not like) & Capra himself into the male characters. Ralph Bellamy plays newspaper editor Holland, who constantly professes his love for Lulu (Stanwyck), while trying to uncover Grover’s secret. At first he is loving & caring, but turns once he & Lulu are married and uncovers Grover & Lulu’s secret. Holland is Frank Fay, at first caring, but ultimately nasty & worthy of swift punishment. Whereas, Grover is portrayed as refined, loyal, sensitive & faithful, all while cheating on his wife & putting career ahead of his responsibilities. He is Capra, which is ironic for a variety of reasons. It’s as if Stanwyck would set aside her life & her career Capra could love her purely. It is the last gasp of a desperate man and reflective of his disillusionment that Stanwyck could have ever been his.

What Capra & screenwriter Jo Swerling (from Capra’s story) do is bring a little of real life into the story by peppering in elements of both Stanwyck’s husband, Frank Fay, (whom Capra did not like) & Capra himself into the male characters. Ralph Bellamy plays newspaper editor Holland, who constantly professes his love for Lulu (Stanwyck), while trying to uncover Grover’s secret. At first he is loving & caring, but turns once he & Lulu are married and uncovers Grover & Lulu’s secret. Holland is Frank Fay, at first caring, but ultimately nasty & worthy of swift punishment. Whereas, Grover is portrayed as refined, loyal, sensitive & faithful, all while cheating on his wife & putting career ahead of his responsibilities. He is Capra, which is ironic for a variety of reasons. It’s as if Stanwyck would set aside her life & her career Capra could love her purely. It is the last gasp of a desperate man and reflective of his disillusionment that Stanwyck could have ever been his.

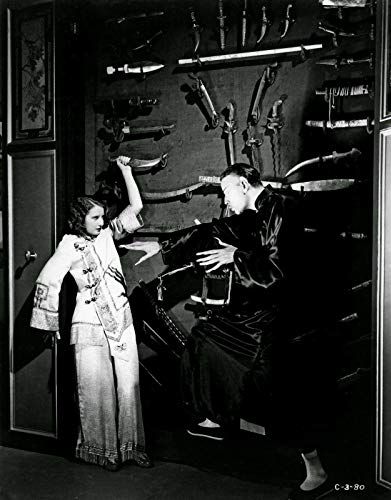

After disillusion comes despair, disgust & abuse, in other words the reflection of love in The Bitter Tea of General Yen (’32). Stanwyck stars as Megan Davis, who arrives in civil war torn Shanghai to be married to her missionary sweetheart, but is rescued/kidnapped by a local warlord, General Yen (Nils Ashter). Yen’s rescue comes as Megan is being attacked in the streets for helping to rescue orphans, but once on his train she is drugged and perhaps raped by Yen, on the way to his palace compound. Their first encounter in the film, when his chauffer driven car hits & kills Megan’s rickshaw driver, gives a hint at the sexual tension which will rise later, as Megan casts a seductive glance in Yen’s way as he leaves. Stanwyck’s expression is a perfect mix of lust & disgust, but certainly interest. Once she awakes in his palace, dressed in silk sleep ware, she waivers between knowing compliance & racist tirades, all the while entranced by Yen’s respectful subservience. He is playing the long game of seduction, showing his sophistication in the face of her racism, while at the same time illustrating his brutality in the murder of peasants by firing squad. Megan superficially represents the purity of female sacrifice, but beneath it lurks a sexual being, capable of miscegenation. Yen can see it in her inner fight to despise him. Played in yellow face by Danish/Swedish actor Nils Asther, Yen is the strongest of Capra’s male protagonists in his Stanwyck cycle. He is cruel & sadistic & his treatment of his favorite concubine Mah-Li immediately intrigues Megan as she watches her wait on him, later to be replicated in the final scene of submission. When Megan gambles her life in an effort to save Mah-Li her commitment to Yen is engaged completely, even if she’s not completely aware of her complicity. The Bitter Tea of General Yen is easily the best & most complete film in the Capra/Stanwyck partnership, but it also the most troubling. The inter-racial relationship turned off audiences of the time, which is not surprising, but the undercurrent of violence & sexual violence is far more deeply felt in watching the film today. If Megan was violated on the train, which seems likely, & was aided by Mah-Li, which also seems likely, then Capra has moved into a far darker arena in his treatment of Stanwyck on screen. The spurned lover, willing to torment and mistreat his ex, ultimately degrading them into the subservience desired. The Bitter Tea of General Yen has is all and kills the relationship once and for all.

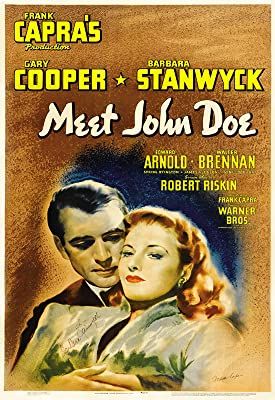

Finally, there is Meet John Doe (’40), made 8 years after The Bitter Tea of General Yen. Both Stanwyck & Capra were at the pinnacle of their early careers, Stanwyck having been nominated for the 1st of her 4 Academy Award nominations (Stella Dallas ‘37) & Capra coming off his third best Director win the year before (You Can’t Take it With You). The film itself is the story of a cynical newspaper columnist (Stanwyck) who crafts an imaginary character to save her job, then builds that character into a national movement. The film is incredibly cynical throughout its first 2 acts, then resorts to a little "Capracorn" for a tidy reconciliation. I paint this film as removed from the arc of the Capra/Stanwyck relationship because it showcases Stanwyck’s ability to be appealing, while being incredibly self-serving & cynical without sentimentality from Capra’s camera or the film’s script. It’s my favorite performance of the Capra/Stanwyck cycle, because it frees Stanwyck from Capra’s prying and lingering camera of the earlier films. She is free to present a range of emotions that are not hindered by stylization or fetish. It’s not the best film in the cycle, however, because it does resort to some simplifications in the third act & relies at times too heavily on Gary Cooper’s awe shucks performance. What makes it interesting, however, is Stanwyck’s performance, which wouldn’t have happened if not for the previous 4 films & the shorthand between writer & director. It’s a fitting conclusion to their shared cycle of films because it represents the freedom from a sentimentalized romance & bitter regrets & opens up the potential of 2 craftsmen working together to create great entertainment.

Sources:

Barbara Stanwyck: The Miracle Woman. Dan CallahanUniversity Press of Mississippi. 2012

Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success. Joseph McBride. Simon & Schuster. 1992.

The Name Above the Title: An Autobiography. Frank Capra. McMillan. 1971

A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel True 1907-1940. Victoria Wilson. Simon & Schuster. 2013.

Sources:

Barbara Stanwyck: The Miracle Woman. Dan CallahanUniversity Press of Mississippi. 2012

Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success. Joseph McBride. Simon & Schuster. 1992.

The Name Above the Title: An Autobiography. Frank Capra. McMillan. 1971

A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel True 1907-1940. Victoria Wilson. Simon & Schuster. 2013.