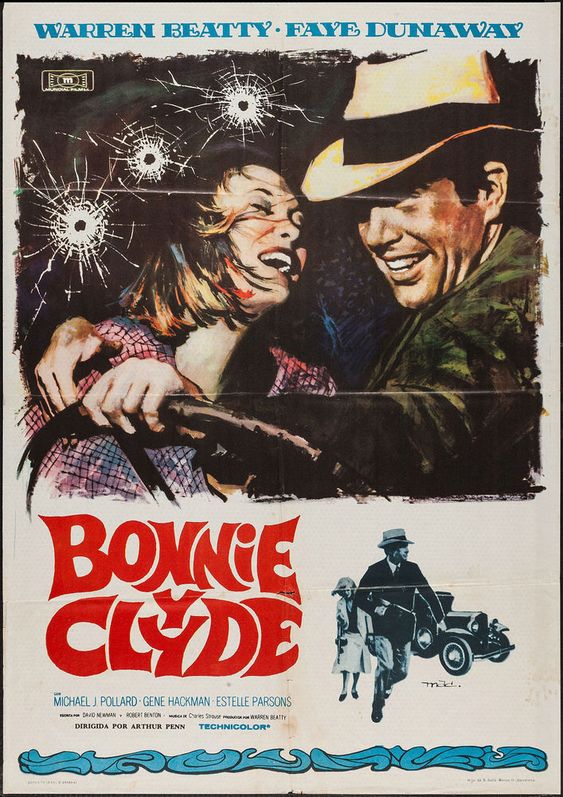

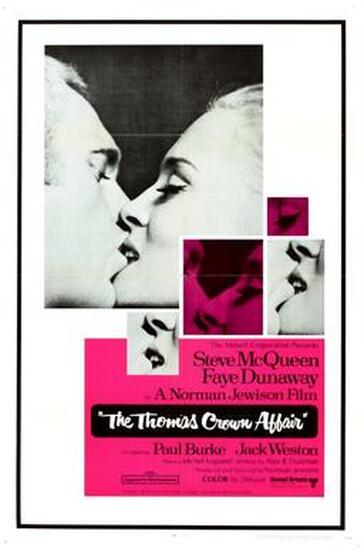

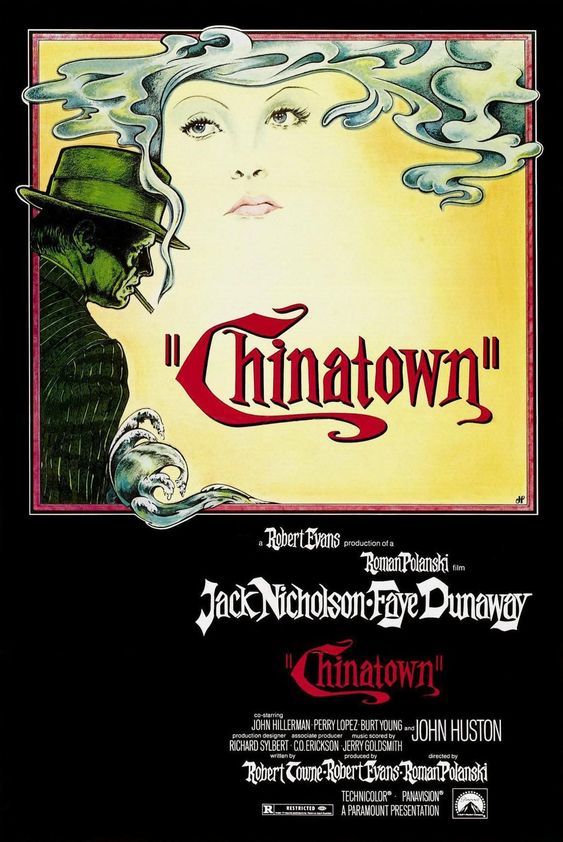

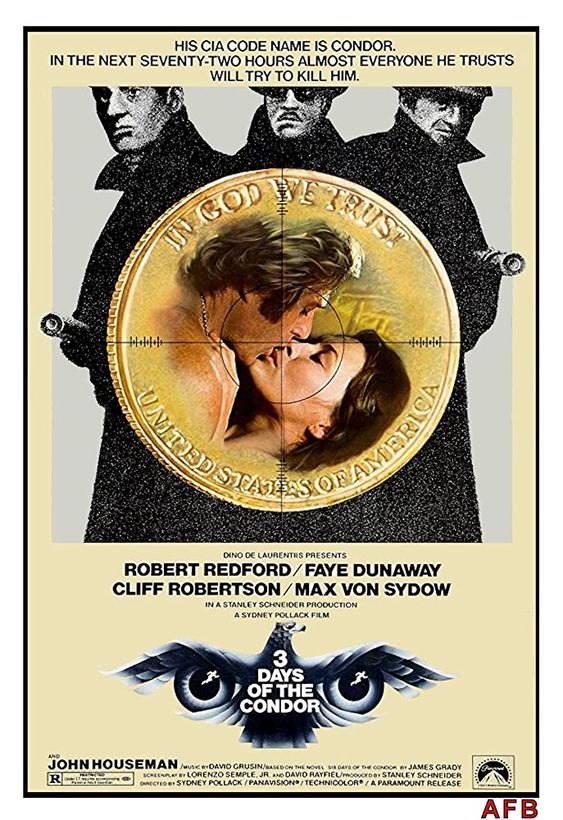

Not many actresses are plucked from relative obscurity and handed the lead in a major Hollywood production that would ultimately change how movies are made, influence a generation of filmmakers and eventually coin the term “New Hollywood.” Dunaway, however, was not the first choice for Bonnie Parker. Natalie Wood was Warren Beatty’s first choice, while Francois Truffaut had suggested Jane Fonda early in the process. At different times Sharon Tate was considered and Tuesday Weld was offered the part, but turned it down. While certainly not the last choice, Beatty & director Arthur Penn could see it from where she was standing, with Penn having rejected Dunaway for an earlier role because “she didn’t have a face for the movies.” Sometimes luck is better than skill and choosing Dunaway was certainly a career changing decision. Her combination of timeless beauty and animal magnetism is perfect for Bonnie’s restless nature and thirst for adventure. Just watch Dunaway’s eyes as they radiate sexual energy and exhilaration after she goads Clyde into their first robbery. The eyes practically glow as they bulge and dart, drinking in Barrow before she tries to ravage him in the front seat of their getaway car. Dunaway’s ability to physically inhabit Bonnie, from her hair and clothes, to her gestures and movements, speak to an actress in total control of the character. Bonnie is used to getting what she wants from boys/men, but Clyde Barrow is a different animal altogether and Dunaway infuses their initial encounter with a knowing sexuality, tinged with desperation, that leads directly to that first robbery. Clyde’s impotence cedes power to Bonnie & Dunaway captures that shift in dynamic, giving her character a confidence and bravado to push them forward, substituting robbery and mayhem for sex. To so completely conquer a character in her first major role was a major accomplishment and signaled Dunaway as an actress on the accent. Even in New Hollywood old habits die hard, so Dunaway’s next feature not surprisingly paired her with Hollywood’s hottest actor, Steve McQueen in The Thomas Crown Affair. Released less than a year after Bonnie & Clyde, Thomas Crown is a full on game of cat and mouse. Dunaway’s Vicki Anderson is bold and brash, all hard edges, as a woman competing in a man’s world. An insurance investigator who always gets her man, Dunaway plays Anderson as a “takes no prisoners” ball buster. Her introductory scene at the airport perfectly sums up her personae as she immediately takes over the one-sided conversation with a gaggle of men, leaving some in her wake, as she grabs one man’s arm for fake intimacy, while dismissing others as she disappears into a cab. Her primary attribute is her competitiveness, but she meets her match in the person of master thief Thomas Crown (McQueen). Their back-and-forth dance of guilt versus innocence culminates in one of the sexiest chess games ever filmed. Chess as foreplay and combat rolled into one scene. Crown: “Do you play?” Anderson: “Try me.” He has no chance as she uses everything in her toolbox to distract Crown, win the game and seduce him cruelly. McQueen’s lined face and pained expressions are perfectly contrasted to Dunaway’s soft skin and porcelain facial features in a masterful word free nearly 5 minutes of screen time. If Bonnie Parker was all pent-up sexual desire, then Vicki Anderson evens the score. Dunaway again radiates strength and confidence, but in a very different character, proving that to be a woman one must be driven and smart, but never above using a little sex to seal the deal. Four years later came Dunaway’s most famous role, as Evelyn Mulwray in Roman Polanski’s iconic celebration and condemnation of Los Angeles in the 1930’s, Chinatown. Mulwray is a different kind of character in that her great vulnerability foreshadows the tragedy of her life and the crux of the film. Appearing for great stretches of the film to be a throwback to the great Femme Fatale’s of 1940’s & 1950’s Film Noir, Mulwray is a cypher, confusing and beguiling detective Jake Gittes (Jack Nicholson) throughout. Dunaway plays her initially as a cold blank canvas, allowing Gittes and the viewer to project emotion where there is none, guilt and deception in all the wrong places and finally empathy and love where it’s least expected. Dunaway’s angular facial features are utilized to perfection in her performance, but it’s her eyes that seemingly absorb emotion in an almost pleading way, wishing safety upon herself through the screen. Evelyn Mulwray may be one of the most tragic characters in American film, but Dunaway never plays her as needy or pitiful, instead filling her with longing for something better, personal safety and ultimately, honest love. Nicholson’s Gittes is a straightforward man who balances Mulwray’s duplicity and his scenes with Dunaway are charged with intense kinetic energy, especially as the couple engages in a twisted seduction, rife with hidden agendas, animal passion and a palatable sense of self-loathing. The amazing scene of Evelyn’s admission of her tragic secret is as emotionally damaging as anything ever put on film and Dunaway is at her peak waffling between admission and denial, ultimately collapsing under Gittes’ ever more forceful questioning. It’s as dizzying to recall as it is to witness and Dunaway was never better in any film she appeared in. Of the five films discussed here, Three Days of the Condor presents Dunaway in what I think is a wholly different type of character and performance. The film itself is a conspiratorial time capsule of the post-Watergate era in which it was made, but also somewhat of a cookie cutter studio film as well. Dunaway’s Kathy is a plot device designed to provide a diversion from the political action and whose appearance doesn’t necessarily determine the protagonist’s outcome. She is eye candy, shows a little skin and has a listening ear. Don’t get me wrong, I like the film and I like Dunaway in it, but the implausible relationship always bothers me when I re-watch the generally engaging film. In fact, I include Three Days of the Condor as part of this list, because it’s the 1 film of the five that I will watch no matter where in the plot I start. It demands the least, but is wholly engaging, in large part because of Redford’s and Dunaway’s chemistry. The romance part, in fact, is the least of the allure of the two stars on screen. I noted this film is different for Dunaway and it’s directly tied to manner of her performance. Unlike the others in this essay, Kathy is pliable; she is neither conniving, nor strong or assertive and she certainly doesn’t seem to be violent or in charge. She is different for Dunaway because she is reactive, instead of active. She allows herself to be dragged through the plot, which is completely different than the other four roles and performances, yet still doesn’t distract from my enjoyment. For me Three Days of the Condor proves the point that a good actor/actress can be enjoyable, no matter the strength or weakness of the character they play. Kathy illustrates that Dunaway can be interesting, for me the most important element of a performance, even if her character is superfluous, which is certainly the case here. Three Days of the Condor is certainly not at the level of Bonnie & Clyde or Chinatown, but it’s the perfect palette cleanser from the cynicism of the final film on my list, Network, Paddy Chayefsky (writer) and Sidney Lumet’s (director) scathing takedown the media and popular culture. Network’s most famous line, uttered by disgruntled and disgusted news anchor Howard Beale (Peter Finch), “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore” perfectly sums up the zeitgeist of the mid-70’s, but beneath that spot-on commentary of contemporary life is an amazing bit foreshadowing the cult of personality that exists today. Beale’s “mad prophet of the airwaves,” as he is billed on his eponymous and highly ranked exploitation show, is the result of a distraught and mentally disturbed man, but he is the product of a cynical world view represented by network entertainment head Diana Christensen, played masterfully by Faye Dunaway, in her Academy Award winning role. Christenson is the malevolent and manipulative representation of unchecked greed and exploitation. She seduces the married network news head Max Schumacher (William Holden) as a distraction to get what she wants, complete control, destroying Schumacher’s life and career. Dunaway uses every bit of her earlier work to craft Christenson from her rotten core out. It’s as if Bonnie Parker’s sexual frustration was now a weapon, Vicki Anderson’s cool manipulation was now wielded with laser-like precision and Evelyn Mulwray’s vulnerability was merely a mask to cripple anyone who opposed her. The character and the way she was played by Dunaway was a seamless mesh of her greatest characters’ most important traits, but it is wholly unique and specific to Christenson, which makes it a terrible joy to watch. And makes it her crowning acting achievement.

0 Comments

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

- Anatomy of a Murder Notes

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed