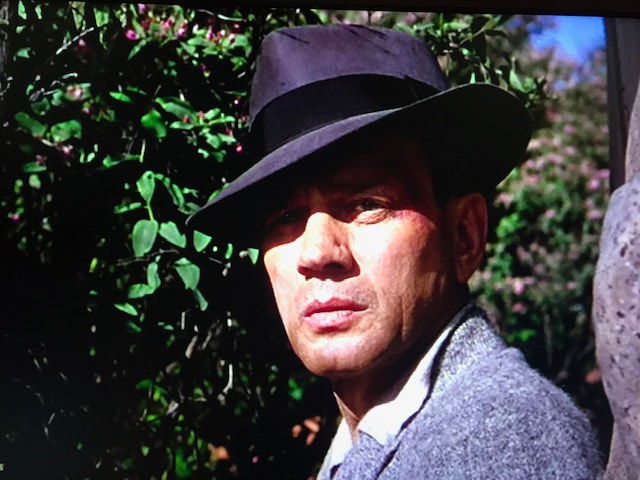

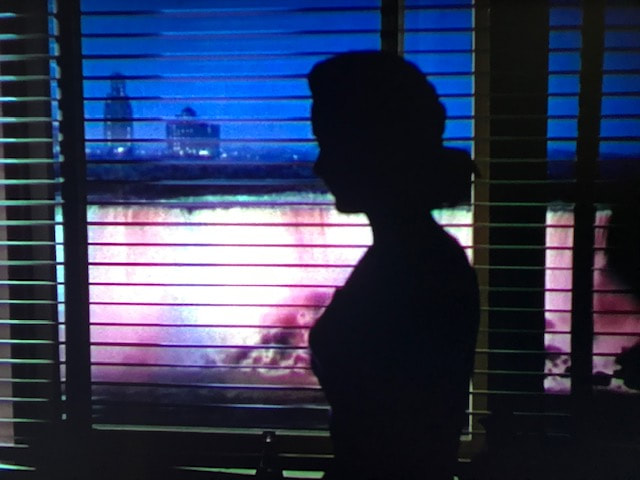

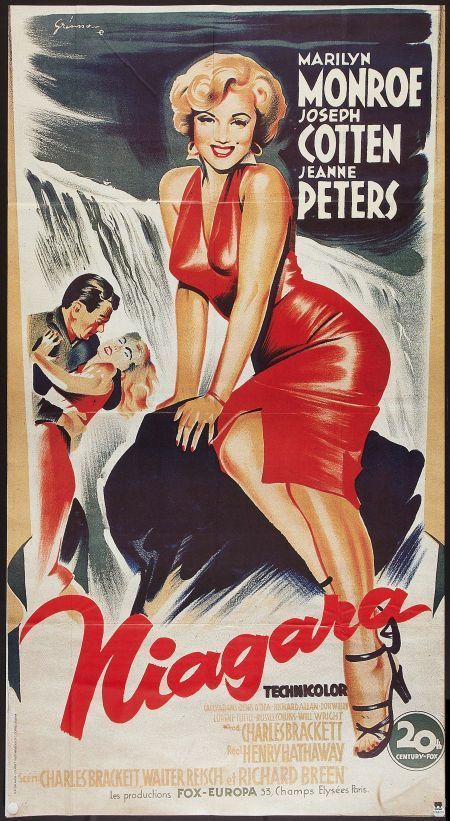

Peters & Showalter play a young couple taking a delayed honeymoon who stay near the Loomis’ at a falls side resort & immediately fall into their troubled relationship when they view George’s violent reaction at a courtyard party. Hathaway & producer/co-writer Charles Brackett combine to give Monroe a truly grown-up role in her ‘A’ picture debut, one that plays on her naturally dynamic & sensual appeal, while also giving the character an inner emotional depth as she plots deception & murder. Niagara truly plays as a launching pad for Monroe as a megawatt phenomenon, but at its core it captures both the potential danger within her sexual appeal, as well as her ability as an actress to create a complex, adult character, perhaps for the last time before her final role in The Misfits. Jake Hinkson, in his piece for the Film Noir Foundation’s Noir City Annual entitled “Marilyn Noir: The Dark Roots of Hollywood’s Blonde Bombshell,” argues that Niagara, which came at the end of a series of parts Monroe played in Film Noir, exposed the havoc that Monroe’s sexuality could wreak on average men, if she were given roles that were serious in nature & gave her a position of real control over her lover. In small, but growing parts in The Asphalt Jungle (’50), Clash By Night (’52), and Don’t Bother to Knock (’52), Monroe could be characterized as playing highly sexualized, but ultimately wholly dependent on & subservient to the men who were in her orbit. It wasn’t until she played Rose Loomis, however, that her sexuality would be utilized for purely nefarious & deadly results. It was also the last time she was given such a role. Within months of Niagra’s January 1953 release, Monroe would be cast in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes & How to Marry a Millionaire, 2 highly successful films that would solidify her role as a light commediane & rocket her to fame. In fact, for the rest of her career she constantly fought against her typecasting, but only with rare occasions, like River of No Return (’54) & Bus Stop (’56), was she allowed to stretch herself as an actress. Her sexuality was similarly cast as transactional, but not deadly, instead being made to be gazed upon & befuddling, but not to the point of murder or lawlessness. Men were meant to ogle her, while she oozed safe & saccharine innocence, used for material gain, but never to dominate in a dangerous way. From the moment Rose is brought on screen in Niagara, smoking a cigarette in bed, naked under a sheet, she is portrayed as a duplicitous character, at the same time tantalizing & aloof, as she smirks at her husband before turning her back. She is in control of the relationship & not content to simply drive her husband mad, but to make his humiliation public, belittling & demeaning. Her parading across the courtyard in a dress George later describes as being “cut so low you can see her knees,” deliberately draws attention to herself & sets up George’s outburst when he destroys the record. She seductively lounges on a step near the newlywed Cutlers (Peters & Showalter), offhandedly singing the song, seemingly attempting to draw her husband out of their cabin in a rage. It’s all part of her plan & Monroe executes it devilishly by casually letting what will happen happen, as neither unexpected nor outrageous, given how she looks, how she’s dressed & how everyone is looking at her. Peters’ husband even stands in for the viewer when he says salaciously, “Get out the fire hose” as Rose approaches the couple. Pulling back to look at how co-writers Brackett, Walter Reisch & Richard Breen utilize location as character one can see that it’s no accident that a place synonymous with love & happiness should be the setting for this story of unhappiness & betrayal. Just as the Loomis’ are introduced as troubled and no longer in love, Polly & Ray Cutler are immediately shown to be in love, sexually active & ready to exploit all that Niagara Falls engenders in its visitors. In fact, the writers were even allowed to sneak a pretty impressive double entendre by the censors when Polly indicates that this won’t be a ‘regular’ honeymoon because she ‘already has her union card’, implying she is more expert in sexual performance than the regular wedding night virgin. The two couples are polar opposites and reflect the looking forward that a place like Niagara can have, while showing the dark underside of looking back at the illusion that it also creates. The slow-moving water, gaining speed as it approaches the falls, moving swifter & swifter, until it gushes over the falls in an image of power & release, very much like the throws of love, but also showing the loss of control necessary to love fully. Once the murderous plot is set in motion, triggered by a song played on the carrion of the (phallic) bell tower, there is no turning back for our unhappy couple. Our young lovers, however, are given over to a travelogue brochure tour of everything Niagara Falls can offer, including the Maiden of the Mist boat ride & the Cave of the Wind, where Polly initially sees Rose kissing another man. Further entanglements ensue as Polly begins to see Rose for what she is, with even George confessing to her that Rose is trying to drive him insane. If Rose were merely a simple Femme Fatale, letting her doomed lover take all the risks, this story would be more straight forward. Rose, however, leaves no stone unturned in her murderous plot, manipulating Patrick to commit the crime, her husband to practically submit to it & the Cutlers to witness the motive & the aftermath. If only there were a perfect crime, Rose would have set it in motion. Unfortunately, there is no perfect crime, but that doesn’t stop both the police & Polly’s husband from poo pooing her doubts & concerns regarding George’s apparent death. When he comes back for revenge, Hathaway is allowed the 2 central set pieces of the film, one a murderous chase in the bell tower & the other a perilous trip in a stranded boat towards the raging falls. Veteran Noir director Hathaway (The Dark Corner ‘46, Call Northside 777 ‘48, Kiss of Death ’47) utilizes the full Noir palette as George pursues Rose up the steps in the bell tower, towards the carrion bells that once symbolized George’s death and Rose’s freedom. Vertical railings give way to shadowed corners & finally to an incredibly beautiful impressionist shot, captured from a bird’s eye camera angle in the shadows of the silent bells. It’s an amazing sequence that is starkly black & white, with all color but Rose’s yellow scarf drained away in shadow. The entire chase is captured without dialogue as well, save George’s accusatory “Too bad, they (the bells) can’t play it for you now, Rose” as he moves towards her. For the often understated & underrated Hathaway, the sequence is a masterclass in suspense, underscores the Noir elements of the film & replaces Rose’s power with George’s. The second action sequence is far more Hollywood standard & accentuates the 3 strip Technicolor as the boat drifts down the river towards certain doom. Peters struggles to survive as George attempts to scuttle the boat while water pours in from above & below. The utter helplessness of Peters belies the intelligence she exercises during the rest of the film, but her determination to thwart George’s escape ultimately makes her the hero of the film, with her taking back George’s strength once & for all. Monroe plays Rose as a dangerous spider, able to kill to suit her fancy. She oozes the sexuality that viewers became accustomed to see in Monroe’s public personae, but in this instance with a sinister glare. She is neither innocent nor pure, out solely for what she wants & has no qualms about exploiting the weakness of her mate to get it. For Hollywood, in the last throughs of the restrictive & sexually repressive Production Code, this was all too dangerous. The scripts could always punish her manipulative sexuality, but they couldn’t always erase the danger in the viewers memories that such a woman could exist. No, I agree with Hinkson, they had to control Monroe’s better animal instincts by making it a joke, a lark, born of innocence, not the knowing sexual predatory that was Rose Loomis.

Sources: Noir City Annual 2017. Eddie Muller, Editor. “Marilyn Noir: The Dark Roots of Hollywood’s Blonde Bombshell.” Jake Hinkson. Film Noir Foundation. 2018. Film Noir: The Directors. Edited by Alain Silver & James Ursini. Limelight Editions. 2012. Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style. Edited by Alain Silver & Elizabeth Ward. The Overlook Press. 1980. Marilyn Monroe: The Biography. Donald Spoto. Harper Collins. 1993.

1 Comment

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

- Anatomy of a Murder Notes

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed