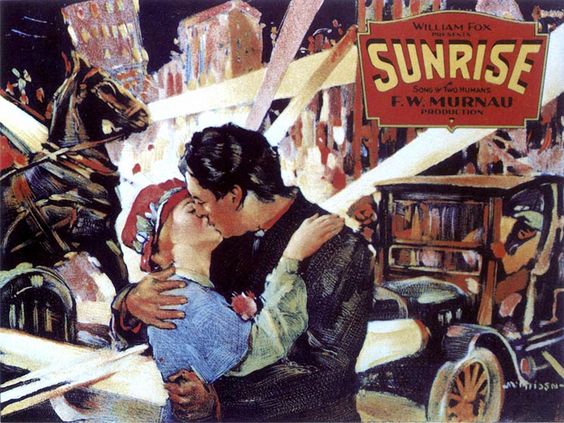

William Fox is not generally named among the lions of the early days of American movie making. Louis B. Mayer at MGM, Adolph Zuker at Paramount, the Warner brothers and even Poverty Row kingpin Harry Cohn at Columbia, are all better known than Fox for creating and shaping Hollywood. Until recently, however, Fox’s name had stood atop a Hollywood Studio for more than a century, but his legacy has been largely forgotten. His Fox Film Corporation was not at the level in volume or prestige as MGM or Paramount during the early years, but as a business man and innovator he far surpassed them both. During the mid-teens, Fox alone took on Thomas Edison’s company monopoly on patents on all of the mechanics of filmmaking and exhibition, winning at the US Supreme Court and ushering in an era of creativity and innovation. Fox also realized that exhibition and production were inexorably tied, so he dramatically expanded the number of theaters he controlled, acquiring smaller chains around the country and buying and building grand movie palaces in major cities. Finally, his fascination with technology led him to develop a superior form of including sound in the exhibition of film. While Warner Bros. developed a synchronized sound on disc (record), that played along with the movie, Fox explored actually putting the sound on the film itself. Consider Fox’s Movietone sound system the Betamax, to the Warner Bros’ Vitaphone’s VHS; one was superior, but the other was initially adopted. So it was that Sunrise was the first feature film to include a Movietone soundtrack, in a limited number of theaters. Because Fox Studios was solidly in the second tier of US film studios, Fox himself sought out one of Europe’s greatest directors to come work for him. After seeing a print of German director FW Murnau’s 1924 silent classic The Last Laugh, Fox was smitten with the idea of bringing a true artist onto his roster of directors. The director had achieved worldwide fame in 1922 for his creation of the quintessential vampire movie, Nosferatu. Utilizing what became known as German Expressionism, the film captured the nightmare-like environment through harsh contrasts in light and darkness, distorted perspective and sharp and contorted angles in sets and buildings. Murnau was a strong visual stylist, relying on very few title cards, instead allowing images to tell the story. The Last Laugh, in fact, had just one title card in a dynamic film about the downfall and redemption of a proud hotel doorman. His style led to more naturalistic performances from his actors and he was credited with freeing the camera from its normal stationary point and shoot position to move lyrically with the action. Fox convinced Murnau to come work for him with a 1 year, $100,000 contract that had Murnau only obligated to make a single film. Murnau’s contract granted him complete control over script, production and budget, a stipulation that Fox was only too happy to grant to a director he call “a genius of our time.” While the contract would be signed in early 1925, it would be 18 months before Murnau arrived in America. During the intervening time he created two additional films that added to his reputation, Tartuffe and Faust, for German film giant UFA. While in Germany, Murnau also attempted to work with Fox underlings to secure the rights to several stories, but he was rebuffed. Finally, he appealed directly to Fox to acquire a German short story called An Excursion to Tilsit to be his first US film. While Fox West Coast production head Winnie Sheehan did not like the story of a cheating husband who plans to kill his wife, he was commanded to acquire it for $15,000. When Murnau finally arrived in New York in July of 1926, he was feted by Fox, who promptly offered the director a four-year contract extension, with a salary elevating to $200,000 in the final year. The director agreed and headed off to California to scout for locations for the rural opening sequence of the film. In what would be a harbinger of things to come, Murnau decided that Lake Arrowhead would be the perfect setting for the country home of the farmer and his wife, but insisted that a small town be constructed across the lake from the already existing community. A robust $750,000 budget was assigned to the film and Fox granted Murnau complete freedom to cast whom he wanted and gave him access to the very best technicians on the Fox lot. At the time of her casting Janet Gaynor was a 20-year-old ingénue with just four credited roles to her name, but already she was the top actress on the Fox lot. In films like The Johnstown Flood, The Shamrock Handicap and Midnight Kiss, all made in 1926, she had established herself as one of Hollywood’s leading ladies. George O’Brien, who would be cast as her husband, had been plucked from stuntman obscurity to star in John Ford’s The Iron Horse in 1924 and quickly established his box office appeal in four subsequent Ford films. Both actors relied on more naturalistic acting styles that were evolving as silent film matured, with Gaynor endearing herself playing sweet innocent damsels and O’Brien as a rugged, but sensitive tough guy. They were both perfect for Murnau, who liked his actors to convey feelings and actions without dramatic pantomime. Once photography began at the Lake Arrowhead location everyone involved realized this would be unlike any film they had worked on before. Murnau’s attention to detail was unique among directors, particularly directors used to working in the Hollywood system of burn and turn camera takes. Instead, Murnau would often engage in as many as 20-30 takes of a single shot, sometimes waiting for light to reflect off a background object to capture the mood he wanted. While the crew and cast enjoyed Murnau’s demeanor and meticulousness, the bean counters began to see a budget quickly escalating, but lacked the power to control it. When Murnau found a specific tree he wanted to use he had the tree chopped down, floated down the river to the shooting location and propped perfectly erect exactly where he wanted to shoot it. When the shock of the move caused the tree to lose all its leaves, Murnau simply ordered thousands of fake leave leaves shipped from Los Angeles and had craftsmen glue them onto the tree, a task which took nearly two weeks. Murnau’s meticulousness extended well beyond how the shot looked to include how the actors moved and emoted. He added 15 pounds of weights to O’Brien’s shoes for the early scenes to give him a lumbering appearance and had him hunch his shoulders to affect the weight of the world resting upon them. Gaynor was made to look more homely by wearing a wig that pressed her hair tightly to her head and was shot to appear even smaller than her normal diminutive stature. Her clothes are heavy and drab and compare poorly to the "woman from the city's" sleek and shimmery black dress. Where Murnau’s attention to detail was most pronounced, however, was in the production design and creation of the sets constructed once shooting moved back to the Fox lot in Los Angeles. Partnering with German compatriot Rochus Gliese, Murnau created a hyper reality, with a mile long trolly track, a great thoroughfare multiple buildings that stretch as far as the eye can see. Using forced perspective, where the lines in the distance converge on a false and exaggerated horizon to add depth, Murnau put smaller people and objects further back, finally having little people and toy cars at the back. The immense set was the largest ever constructed and cost more than $200,000 to build, but it gave Murnau the look and feel of chaos that he wanted to overwhelm the countryfolk. Two particular scenes perfectly illustrate what Murnau was after and how he executed it on screen. The first is the scene between the husband and his lover in the marsh. The siren call of the mistress lures the man out towards the lake, leaving his wife alone at home to imagine their bucolic former lives. As full moon appears over a fog covered march as the man trudges towards his mistress, the camera following him as he moves through bushes and trees, almost in a circle, as he finally moves straight towards the camera itself. The camera spins on its axis to move from the man’s perspective, resting on the mistress as she powders her nose, the moon above her providing her a vanity light. The man appears, with only the moon between them, they embrace and madly kiss. Told entirely in images, the scene captures all the emotion, dread and longing that sets the story in motion and is unlike anything in silent film in the fluid and effortless nature of the camera movement. The viewer is the voyeur, floating at the edge of the scene, but never intruding into it. It’s stunning camera work by Charles Rosher and Karl Straus, designed eloquently by Murnau to bring the viewer into the story The second scene creates the sense of danger and foreboding as the couple arrives in the city. Murnau creates a frenzy of danger around the couple as they make their way across the busy city street. Cars zoom by in the foreground, people bustle along the sidewalk, cutting in front of the camera creating a barrier between the viewer and the couple, all in random fashion as the man holds his wife tight, belying his deception from moments before. They are now alone on an island, but the bond between them is broken, even as he inches towards realizing his love for her. Later, Murnau comes back to the busy street, but this time the couple’s island is shared between them and the chaos does not touch them. Utilizing in-camera double exposure, combined with dual layer matte shots, the couple now exist unto themselves, as first cars, then bicycles and people flash around them, the city even morphing into a serene country glade as they walk oblivious. The use of sophisticated optical effects momentarily lifts the couple out of their surroundings and back to a happier time, until the city comes crashing back around them. But this time they are united, safe and joyous in each other’s arms. Technical wizardry, combined with heartfelt and real emotion is what elevates this scene, illustrating Murnau’s combined talents as an artist and a craftsman. While shooting, Murnau would only allow O’Brien, Gaynor and his editor see the daily film, excluding Fox executives. When he completed with initial 10 reel cut of the film there were only 18 title cards, which would have been the fewest of any feature length American film to date. With his cut “in the can” Murnau boarded a boat to complete some residual responsibilities for UFA in Germany, while Fox West Coast executives praised the film after Northern California screenings. Their praise, however, belied a grave concern about the public appeal of the film. Yes, it was beautiful. Yes, it was emotionally engaging. But it was at its core a European film. The story was not modern and featured the threat of matricide and the stars were not at their glamourous best. How would they market the film? When the film premiered in New York the studio chose to debut it at the 1,100 seat Times Square Theater, instead of Fox’s recently purchased 6,600 seat Roxy Theater, fearing the cavernous space would appear even more empty as time went on. While the decision of theaters was telling, the gravest mistake Fox made in releasing Sunrise was in the inclusion of a 20 minute Movietone sound newsreel call “Voices of Italy” as the opening feature of each performance. In a cynical attempt to appeal to a wider and separate audience to boost box office, “Voices of Italy” featured one of the earliest recordings of Benito Mussolini, snippets of the Vatican Choir and various Italian tradesmen all meant to draw in the large Italian population of New York City. What happened was that both audiences came away unhappy. Those that came to see “Voices of Italy” hated Sunrise and vice versus. While critics praised the film as a classic, the box office slump and word of mouth limited attendance before the film rolled out to additional markets, forever muting its box office appeal. For a film that ended up costing $1.2 million it was probably too high a mountain to climb to be considered a success, however, when the film debuted on the west coast there was another round of critical praise and stronger box office where expectations had been muted in advance. The film would go on to win three Academy Awards and the inaugural event in May of 1929, noting Sunrise’s capstone on the silent era with its artistic award, as well as for Janet Gaynor’s performance and the gorgeous cinematography by Straus and Rosher. After Sunrise Fox and his executives curtailed Murnau’s freedom and he made 2 more films for the company, both of which were significantly altered from his version, with Four Devils now lost. After exiting his Fox contract, the director went to the South Pacific to work with renowned documentarian Robert Flaherty to direct Tabu, which secured distribution through Paramount for a US release. A week before its March 18h, 1931 premiere Murnau died after injuries sustained in a car accident. He was 42 years old. William Fox was able to overcome the financial setback of Sunrise and continued to push his innovative sound on film technology, as well as building and expanding his distribution network. By 1929 his empire was worth an estimated $300 million dollars and he had enough power to have a deal in place to buy all of the assets of Loews, the parent company of MGM Studios and all their associated theaters. He was at the mountain top of his industry, but it was short lived. A July 1929 automobile accident left him hospitalized and near death. As events of that fall began to take hold, it became apparent he had overextended himself financially and when banks called in his notes after the October Stock Market crash, Fox, still in his hospital bed, was left near penniless. He lost the MGM deal and in 1930 was forced to sell his empire for a mere $15 million dollars. He never made another film and by 1941 was actually sentenced to prison for bribing a judge, sealing his fate on the dustbin of history. While both William Fox and FW Murnau have been largely forgotten outside of film studies courses, their legacy of creating a unique and endearing piece of cinematic art cannot be understated. Without the drive of Fox to elevate his company artistically and Murnau’s talent and perfectionism, Sunrise would never have been made. Murnau’s genius took a simple story of betrayal and love and crafted a masterwork of style, emotion and wonder. Enjoying the five more than 95 years after its release is testament to its enduring quality and place among the greatest achievements in the quintessential artform of the 20th century.

*A final footnote. While William Fox was one of the early pioneers in archiving film as an artistic endeavor, even approaching congress for money for a national film archive, more than 90% of Fox Studios silent films were completely lost in a 1937 fire at their New Jersey warehouse, including Sunrise. As late as 2003 archivists from around the world were able to combine multiple pieces of existing materials to restore Sunrise to its glorious current state. 2oth Century Fox, the company created in 1936 out of the near bankrupt ruins of William Fox’s empire, partnered with the British Film Institute to restore the film for future generations.

0 Comments

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

- Anatomy of a Murder Notes

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed