|

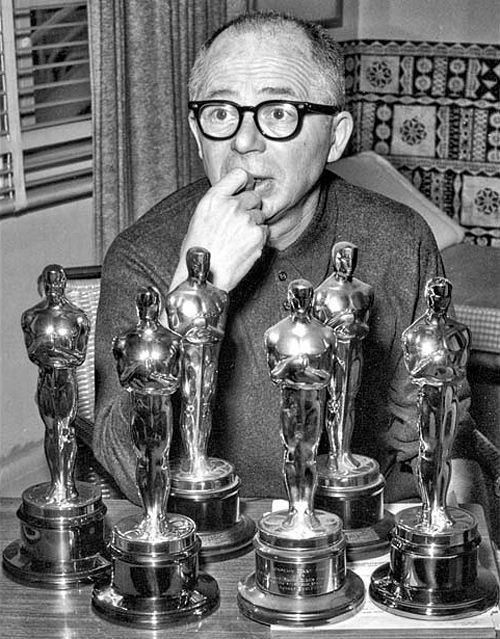

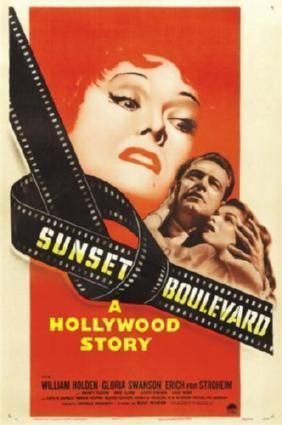

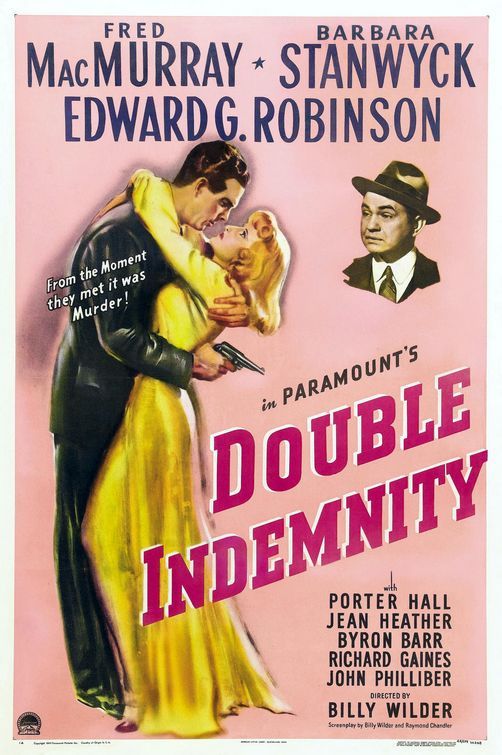

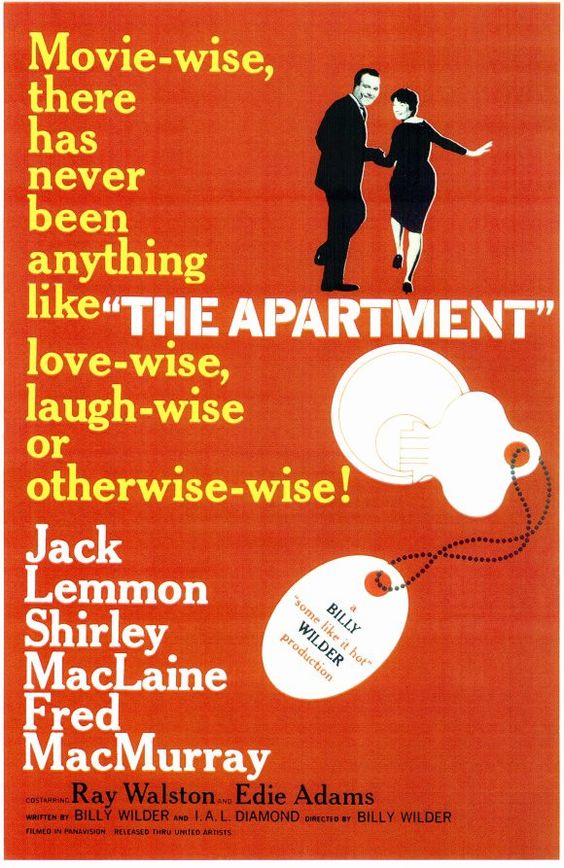

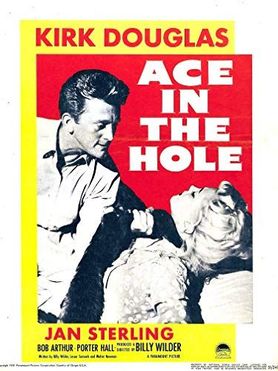

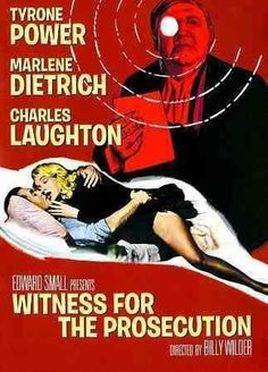

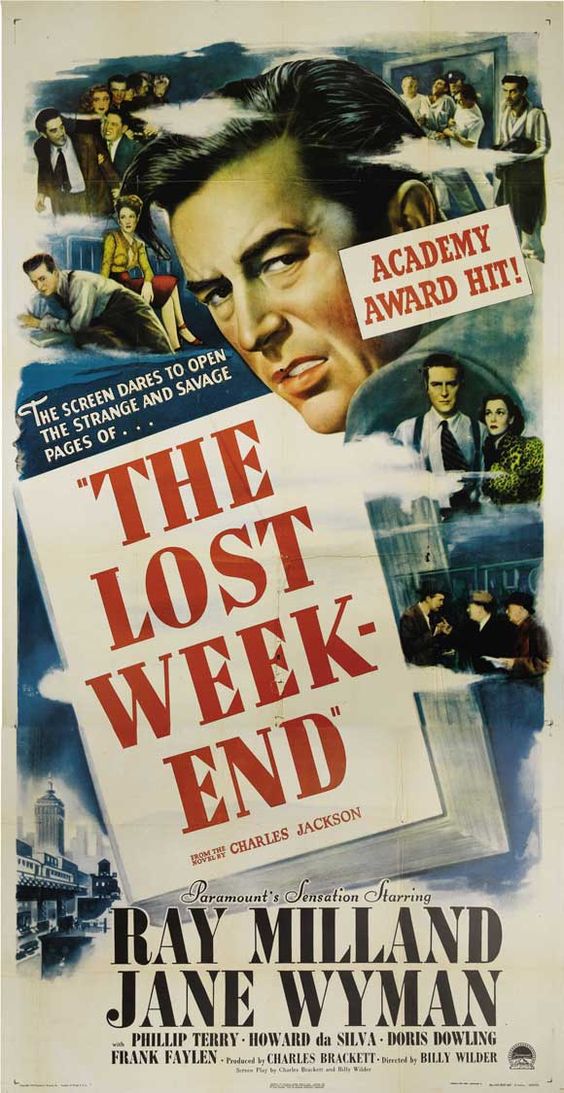

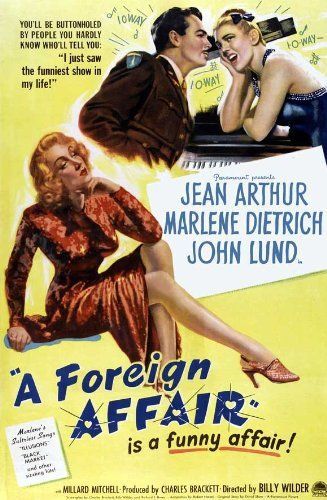

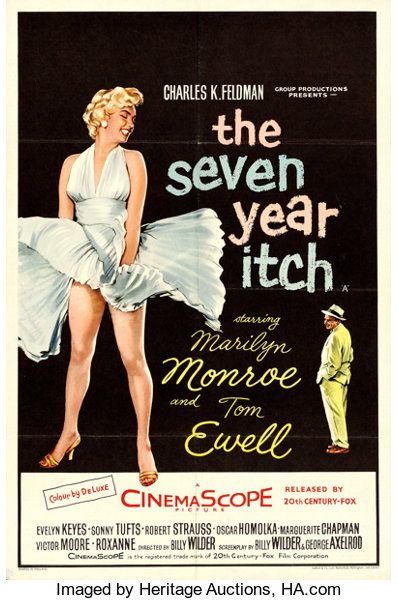

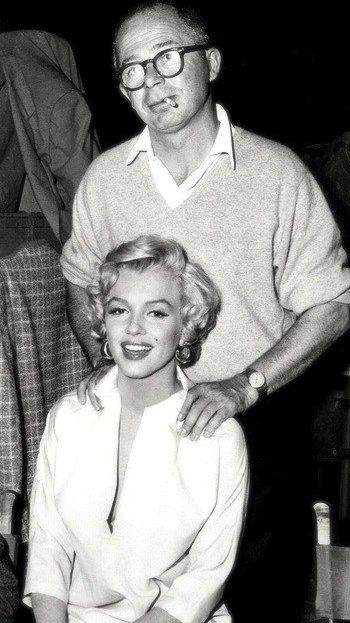

The Rationale: Billy Wilder may be the greatest director in the history of American movies. He was never the most innovative director, however, he hardly used the camera to add dimension to the story & he never placed visual style at the forefront of any of the films he made, but what he did was craft stories about people that were interesting & told them in an effective way. For Wilder the script was the thing & in every genre, in whatever era & in whatever style, his best films are elevated to classics, his good movies are incredible & even his lesser films are genuinely enjoyable. His scripts, which netted him 11 Oscar nominations & 3 wins, were sacred texts on the set & he rarely allowed any actor to change even a word, but he never worked alone writing them, preferring several longstanding partners throughout his career. He put one of the capstones on the Screwball Comedy with his script for Ninotchka (’39), he helped define the Film Noir movement with Double Indemnity (’44), was the first to use Berlin in a post-war film with Foreign Affair (’48), made what is considered the best film about Hollywood with Sunset Boulevard (’50) & crafted what is generally agreed to be the best comedy of all time in Some Like it Hot (’59). In between, before & after he made movies that shaped popular culture, romance, war & commented on the media, modern business & politics, both sexual & otherwise. Billy Wilder was a master storyteller, who just happened to write and directed motion pictures, creating a legacy that can easier be set beside & more likely set atop any directors career works as the greatest in film history. Separating Billy Wilder’s Top 10 is no easy task. Films like One, Two, Three (’61), The Major & the Minor (’42) & Sabrina (’54) did not make the list, but would be shoo-ins for most director’s Top 10. For me, however, choosing the top films was easy because Sunset Boulevard (’50) brilliantly combines an insiders respect for the industry that creates magic, with a cynics eye view behind the magicians curtain. Wilder, in essence, bites the hand that feeds him by commenting on the throwaway nature of fame, the superficiality of Hollywood & the stupidity of studio management, all told through the jaundiced eyes of a disillusioned writer. In a master stroke, Wilder saves his finest commentary for the treatment of the writer, his chosen craft & first love, by having the writer (William Holden) & narrator of the picture, literally thrown away & discarded as the movie opens. The film reflects on the glory of Hollywood history by starring Gloria Swanson & featuring Erich Von Stroheim, Buster Keaton & Hedda Hopper, but shows the past greats as largely shells of their former selves. Only director Cecil B. DeMille (Cleopatra ‘34, Sign of the Cross ’32) escapes this faded glory, still a vibrant presence on the Paramount lot as he ignites Norma’s illusion of returning to the screen by offering to rent her car. Each moment, from Joe’s stumbling into the house to avoid repo men, to the back story between Max & Norma & the story writing flirtation of Joe & Betty are spot on in their conciseness. Every word is perfection, concluding with the most famous line of them all “All right, Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up.” Sunset Boulevard shows the master at the peak of his craft, unafraid of condemning & criticizing the very industry that supports him & nurtures that talent. Depending on my mood the next 2 films could be flipped on any given day. Both Some Like It Hot (’59) & Double Indemnity (’44) are arguably the greatest films of their type in American film history. Often, the decision is based on which film I saw most recently, so today its Some Like It Hot at #2. I recently wrote a piece on Some Like it Hot for a blogathon about cross-dressing in the movies (https://bit.ly/2IbTF06), but at its core the movie is just plain funny. Sure the gender bending roles are played for laughs, but Wilder seemed to have bigger fish to fry regarding how the sexes take on roles to impress or fool the opposite. Watching first Tony Curtis & Jack Lemmon shimmy through the train station, only to juxtapose it with Marilyn Monroe’s shimmy, is priceless visual comedy. Coupled with the usual wit of a Wilder screenplay with classics like “…nobody’s perfect “, “Look how she moves. It’s like Jello on springs” & “oh Daphne, how can I ever repay you?” “I can think of a million ways…and that’s one of them,” Some Like It Hot is the best film marrying physical & verbal comedy that I can think of. Quite simply, it is the story of 2 down on their luck musicians who happen to witness the St. Valentine’s Day massacre in Chicago in 1929 & are forced to impersonate women to get a gig in an all-girls band to escape the mobsters. When the band’s vocalist, Sugar Kane, just happens to be Marilyn Monroe, however, both ‘Daphne’ (Jack Lemmon) & ‘Josephine’ (Tony Curtis) pursue her, with Curtis taking on yet another disguise as rich oil baron Junior. Daphne is wined in dined by real millionaire Osgood Fielding III (Joe E. Brown), while the 2 hideout from the mobsters who happen to show up at their Florida hotel. At the end, the mobsters get their due and true love blooms in the most interesting places! Love does not bloom in Double Indemnity. It rots from the inside out as Insurance salesman Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) is first seduced & then manipulated by Phylliss Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck) into killing her husband. The structure, told in voice over flashback, the rat-a-tat-tat dialogue & the chiaroscuro lighting all set the standard & the tone for Films Noirs to follow. Wilder & co-screenwriter Raymond Chandler (creator of private dick Phillip Marlowe) distilled James M. Cain’s (The Postman Always Rings Twice) tale of infidelity, murder & double-cross to its very essence, creating the template for Noir & the highpoint of the movement. When the film opens on a stumbling & clearly injured man making his way to his office Dictaphone, there is no way to know that the viewer will be privy to the confessions to end all confessions. Walter Neff outlines his part in the murder of a policy holder for the double indemnified life insurance that he sold the wicked widow…and boy is she wicked. Barbara Stanwyck, the greatest of all actresses, is at her man-eater best, chewing up poor Walter with the flick of her ankle bracelet and the flip of her platinum blonde wig. He has no chance, but to go along with idea to kill the husband, and then to plot the crime for maximum insurance benefit. Only company insurance investigator Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson), in what I think is his greatest performance, stands between Walter’s lust and Phyllis’ greed. As the pressure mounts & the plan goes haywire, the joy is in watching the noose tighten, all the while Wilder shortening & speeding up the dialogue to increase the sense of inevitability, with Keyes commenting ‘murder…is like taking a trolley ride…it’s a one way trip & the last stop is the cemetery.” Billy Wilder was often called the most cynical man in Hollywood & his take on most things did reflect a rather bleak view of his subjects. Perhaps resulting from his time fleeing the Nazi’s in Europe, his cynicism also held up a mirror to post-war America in a way most film makers didn’t dare. Sunset Blvd is but one example, but that’s limited to Hollywood. The Apartment (’60), on the other hand, hits America right between its capitalistic eyes by showing the ruthless and impersonal world of big business. C.C. Baxter (Jack Lemmon) is an office grunt trying to get ahead by allowing upper management to use his apartment for trysts with their mistresses. A hopeless romantic, C.C. falls for the beautiful elevator girl Fran Kubelik (Shirley MacLaine), who just happens to be the mistress of the dastardly Jeff Sheldrake (Fred MacMurray). The more executives that use the apartment the higher C.C. is promoted, finally landing as Sheldrake’s assistant…with a key to the executive washroom & a windowed office. He is used and taken advantage of just as much as the nameless parade of women who frequent his apartment, but he in turn loses his soul, while simultaneously falling in love. Suicide, divorce, or rather the promise of divorce, drunkenness & infidelity are all in a day’s work at the unnamed insurance company where C.C. toils, finally realizing he’s better off somewhere else. The melancholy ending certainly cannot be called happy, but there’s a certain charm that at least 2 people have escaped the soul crushing world of big business, but of course neither has a job… Lemmon & MacLaine are uniquely suited to their roles as the nebbish loser & the innocent ingénue, respectively. Lemmon & Wilder partnered for 5 movies together, but The Apartment is more Lemmon’s than any of the others. His little bits of business while he flits around the apartment, for instance, bring great depth to the character, while his eyes reflect repeated sadness & disillusionment better than anyone. C.C. is a full human being & balances wonderfully with MacLaine’s wide-eyed doe in the headlights. There is sweetness at the center of both characters & it is Wilder’s genius that he is able to tease it out gradually as the movie plays out. Chuck Tatum (Kirk Douglas) is an egotistical, self-satisfied, cynical & unemployed newspaper man out to get back on top any way he can. In Wilder’s Ace in the Hole (’51) Tatum helps manufacture a sensational news story that captivates the national. Looking for anyway to get his New York gig back he unscrupulously exploits a man’s perilous entrapment in a collapsing cave for maximum media exposure, manipulating local authorities, politicians, curious onlookers & the man’s family. Wilder has a field day commenting on the perilous trust between the press & its audience, making it clear the audience is stupid & gullible & the press is duplicitous & predatory. It is Wilder at his most cynical, casting his net across as wide a swath of humanity as possible. There really are no sympathetic characters, as every person, led by Tatum, is looking for something from the unfolding tragedy, even the victim himself. Ace in the Hole was Wilder’s first critical & audience flop & Paramount executives were not pleased with the effort, renaming it The Big Carnival for its release. Witness for the Prosecution (’57) & The Lost Weekend (’45) are both character driven films made great in part because of the performances of Charles Laughton & Ray Milland, respectively. Because Wilder insisted on precise recitation of his scripts, both actors’ performances can be argued to be extensions of Wilder himself. Laughton plays the blustery barrister who defends murder suspect Leonard Vole (Tyrone Power, in his final film role), through the twists & turns of the Agatha Christie penned play adaption. He is a commanding presence, brought to comical distraction by his busy body nurse played by his real life wife Elsa Lancaster. That Laughton can overshadow a wonderful performance by Marlene Dietrich, as the accused’s wife, is a testament to the dynamic command he exibits in every scene. He is pompous & self-absorbed, but lovable & devoted. His alarm & momentary disillusionment in the final scene is immediately replaced by his sure footed insistence to take on a new client. This shift perfectly encapsulates what makes his performance great. Milland, on the other hand, bases his performance on a million small performances, as his character Don Birnam, fools himself & those around him as he struggles mightily with alcoholism. Wilder claimed to have said before shooting even began that the actor who portrayed Birham would win an Oscar & he was right. It is a tour de force picture about the ravages of the disease that doesn’t pull any punches or let Don off the hook. Made in ’45 The Lost Weekend is as bleak a picture as I can remember from the time period. Milland’s performance is complete in its physical & emotional depth as his failed writer falls deeper & deeper into a near death spiral as the drinking intensifies & his desperation grows. When Don pawns the coat of the woman who loves him (Jane Wyman) he hits bottom, determined to end his addiction the only way possible. Redemption is hard won and certainly not final. As with many of Wilder’s films he lets the words speak for themselves, rarely embellishing his shots with camera movement or aggressive cutting. Instead, he chooses specific moments to add dimension to the image by framing depth & allowing the action to take place within the frame. It is this simplicity that focusses the viewer on the words and the emotion the characters emote. Salag 17 (’53) is one of the first picture to make fun of the Nazi’s & uses a World War II prisoner of war camp for both physical & verbal humor. Co-written with Edwin Bloom, in their only collaboration, Stalag 17 centers around JJ Sefton, William Holden in an Oscar winning performance, a morally ambiguous character who has no trouble trading with the Nazi’s if it suits his needs. Trafficking in everything from cigarettes to pantyhose, Sefton comes under suspicion for ratting out fellow prisoners after they are shot trying to escape. The ambiguous nature of life in the barracks makes it difficult to determine who the spy amongst the prisoners truly is & Wilder shot the film in chronological order to keep the actors guessing as well. Broadly imitated by the TV show Hogan’s Heroes, Stalag 17 was held up for release for nearly a year because executives at Paramount feared no one would want to watch a movie about prisoners of war. Holden’s performance, however, is masterful, constantly teetering on the edge of cocky indifference & determined self-preservation. When he is beaten by his barrack-mates for further suspicion, Wilder exposes the animalistic nature of mob mentality & the fine line between the jovial comradery exhibited amongst the prisoners & the harsh surroundings they find themselves in. Stalag 17 is on its surface a sensational depiction of life in a Nazi prison camp, but at its core it illustrates the thread by which all life hung behind enemy lines. Finally, when Sefton is given a chance at redemption, he thinly masks his humanity in the guise of a moneymaking venture to maintain his veneer of indifference, even as he risks everything to save a fellow officer. 5 years earlier, Wilder had been one of the first civilians to bring a crew into Berlin for location shooting on the film A Foreign Affair (’48). The shots he came away with are haunting even now, but I can’t imagine the impact they would have had on late ‘40’s audiences, but they lend a gravitas that clearly could not have been achieved on a studio soundstage. A Foreign Affair focuses on a love triangle between an Army Captain (John Lund), a suspected Nazi sympathizer (Marlene Dietrich) & an American congresswoman (Jean Arthur) sent to investigate both of them. While there are moments of great humor found in the stupidity of the military bureaucracy & the libidos of young soldiers, the destruction of Berlin & the impact on its inhabitants weighs heavily on the movie. Arthur, a rock solid comedienne, counter balances the flatness of Lund’s performance, but the film is really Dietrich’s. While she was loathe to play someone even suspected of being a Nazi sympathizer, her performance is one of the richest in her career, complete with a world-weariness that stays with you long after the film is finished. Her performances in the bombed out nightclub are every bit as good, & in some cases better than her singing in her more famous Von Sternberg films. Wilder often claimed that Dietrich was his favorite actress to work with & their collaboration makes A Foreign Affair a very memorable film. Billy Wilder worked with Marilyn Monroe on 2 films, Some Like it Hot (’59) & The Seven Year Itch (’55) and the experiences were quite different according to Wilder biographer Kevin Lally. Whereas Monroe’s tardiness & occasional inability to recite her lines correctly were Wilder’s biggest complaint on Seven Year Itch, he felt the overall experience was worth the hassle of having America’s sex goddess as his leading lady. On Some Like It Hot, however, Monroe’s insecurity & inability to consistently work drove Wilder mad & he vowed never to work with her again. Of all the films on this list The Seven Year Itch was the most surprising to include, but Monroe’s performance is one of the best of her career & she wonderfully recites Wilder’s dialogue in a mindlessly innocent way. As Wilder noted, her performance is almost touchable from the screen, radiating sexuality without an ounce of self-awareness. Wilder always looked at the picture with regret because he was somewhat restrained by the Production Code’s strict enforcement that adultery could not be played for laughs. Whereas in the play, the milquetoast book editor (Tom Ewell) ends up bedding the girl (Monroe), the Production code forbade such an action, but Wilder wanted to imply that sex had occurred without showing it (he wanted to have a cleaning lady find a hair pin in his bed while making it up). Regrettably, he was overruled, but the film doesn’t suffer that much for the frustration of Ewell’s character. Clearly, The Seven Year Itch is the wild card in this list, but the simple enjoyment of the 2 performances & the simplicity of the direction make it a very enjoyable movie. Billy Wilder was a disciple of German director Ernst Lubitsch, having penned Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife (’38) and Ninotchka (’39) for the master early in his Hollywood career. In some circles, Lubitsch was credited with inventing the romantic comedy with his silent films & 1930’s sophisticated comedies & if he did then Wilder carried on the torch and amplified it in many of his films. Where Wilder may have proven himself greater than the master, however, was in the wide variety of genres & types of films that he made & the longevity of his career. The zenith of his career, reflected in this Top10 list ran more than 16 years, but the entirety of that career produced at least another 10-12 films worthy of this list. He was a master’s master, filling his films with great performances surely built upon the genius of his words & in doing so he simplified film to its essence: People, far more interesting than the audience, behaving well & behaving badly, but always speaking & acting as if they were smarter (or dumber) than anybody we’d ever met.

Sources: Wilder Times: The Life of Billy Wilder. Kevin Lally. Henry Holt. 1996.

1 Comment

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

- Anatomy of a Murder Notes

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed