|

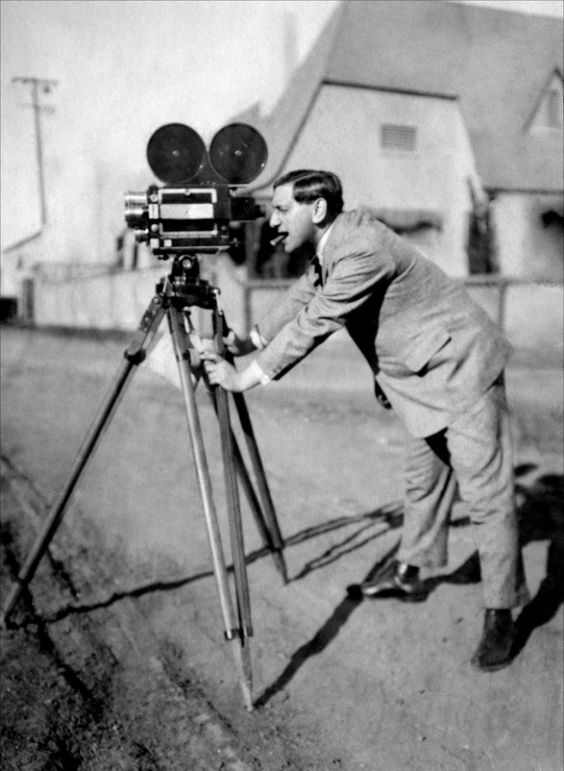

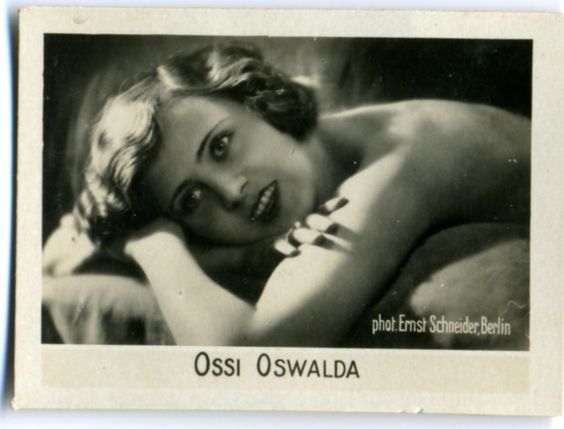

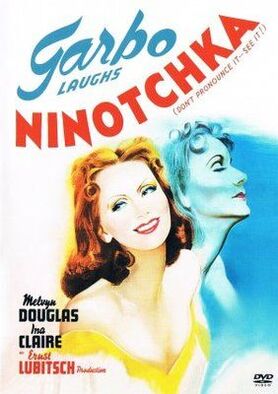

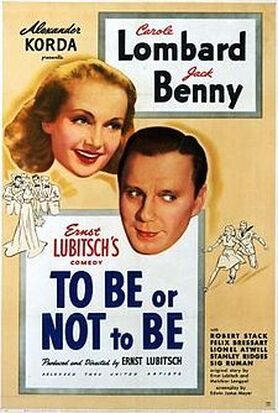

The Rationale: Ernst Lubitsch is best known today for his sophisticated comedies on the early 1930’s. For a time he was the highest paid & most well-known director in Hollywood. Leading up to & launching his fame in Hollywood, however, Lubitsch was the most popular director in Germany in the late teens and early 20’s, as well as a dynamic director of both silent & sound musicals. All his films were known to have “the Lubitsch touch,” that is they possessed a certain style unique to the director that reflected his continental attitudes towards sex, sexuality & marriage, while never talking down to the audience. In essence, that is the genius of Lubitsch; he always assumed the audience was smart enough to catch the innuendo, without having it spoken or beaten about their heads. A closed door could mean a sexual liaison; a time-lapsed clock could mean a long sexual liaison; and breakfast together could mean an all-night sexual liaison. Sure his films were about sex, but more importantly they were about relationships, mature relationships between consenting adults, sometimes within the bounds of marriage and sometimes outside. The people in his movies were smart, spoke very well and above all were of a class unlike anyone in the audience. They were also quite often European, or from some exotic pseudo-European country, that allowed them to flaunt their ‘different-ness’ & make their behavior more explainable. While he only received 1 Academy Award nomination (he did receive an honorary Oscar in 1947), Lubitsch is often credited with creating the basic template for the movie musical & the romantic comedy & was revered by directors as wide ranging as Alfred Hitchcock, Jean Renior & Douglass Sirk & was the mentor & idol of Billy Wilder. Perhaps he is not better known today because he dealt with adult relationships, comically showing (or alluding to) adultery, prostitution, serial philandering & an occasional threesome. His films paid the greatest price with the implementation of the Production Code in 1934, by not being approved for re-issue in theatres & later for airing on television. His style of filmmaking changed after 1934 as well, with the Code’s strict guidelines regarding anything regarding sex & sexuality significantly tamping down Lubitsch’s social commentary on relationships between the sexes. While he still made very fine pictures after 1934, including The Shop Around the Corner (’40), Angel (’37) & Heaven Can Wait (’43), only 2 films from that later period made the Top 10 noted here, Ninotchka (’39) & To Be or Not to Be (’42) and both of these films relied on social & political satire for their biting humor. Lubitsch was the “master’s master” & a great storyteller, but his genius was in the concise way he could ring humor from a glance, a look or a gesture, without any wasted motion & without any cheap tricks. He was brilliant in his direct use of innuendo & a master of the closed door. I’m cheating here a bit because I’m rolling 3 of Lubitsch’s German silents into one spot because they’re all so good & I couldn’t include 1 without the other 2. They also each star actress Ossi Oswalda (1897-1947), so there is a unifying element to my madness. The first of these 3 to be released was I Don’t Want to Be a Man (’18), which predates Gardo & Dietrich’s cross-dressing roles of the ‘30’s by more than a decade. In it, Oswalda plays an impetuous teen, fed up with being bossed by a strict guardian, who decides to dress in top coat & tails & attend a ball, but finds being a man is not as easy or privileged as she thought. When she challenges her guardian for the attention of a young woman, only to both be thwarted, she ends up drinking with the guardian & the two find a mutual attraction. That Lubitsch puts 2 “men” together in an intimate embrace & then openly kissing, amplifies his questioning and undermining of gender roles for both the male & female character. Oswala’s next film, The Oyster Princess (’19) has her playing the spoiled daughter of the American Oyster king, Mister Quaker, who is out to marry off his daughter to European royalty to secure their place in society. Another comedy of mistaken identity ensues as first a valet to a penniless prince, then the prince himself, slyly named Prince Nucki, attempt to woo the randy Oswalda. At the wedding a spontaneous “Foxtrot epidemic” breaks out as the guests & servants all symmetrically twirl & turn from room to room; the first example of a movie musical number. The film closes as the Oyster King peers knowingly through the keyhole of the newlyweds. Finally, there is The Doll (’19) where Oswalda plays the daughter of a famous doll maker, who is forced to impersonate a lifelike facsimile of herself to fool the son of the local Baron, who wants to marry the doll. Again, Lubitsch bravely toys with relationships outside the social norms of the time to humorous effect. When the boy takes the doll back to a monastery to marry her, Oswalda creatively fools the boy, but the monks lasciviously catch on and mayhem ensues. While Oswalda’s performances bind the films together, it is the germ of the Lubitsch touch that makes them wholly memorable. Oswalda was a talented comedienne & perfectly suited to the sexual elements of Lubitsch’s pictures, as well as their physical nature, but all 3 are stamped with Lubitsch’s fingerprints from frame one. The ‘Foxtrot epidemic’ is but one example of creative use of the frame that was years ahead of other filmmakers. His use of the closed door was already a key, if muted, element of his plot making, no more so than in The Oyster Princess where clearly sex is implied behind the final door in the film. Finally, as alluded to above, Lubitsch was already exploring the very adult notion of sex for comedic purposes in all 3 of these films, granting Oswalda a clear & obvious sexual drive that motivated her characters actions & drove the storylines. The Lubitsch of his later American films was certainly present in these silent and combined with Oswalda’s brilliant performances they are enjoyable romps that foreshadow the greatness to come. Casting forward a few years it’s strange to realize that it wasn’t Lubitsch’s brilliant comedies of the late teens that caught Hollywood’s attention, but his silent spectacles made in the early ‘20’s. They apparently rivaled Cecil B. De Mille’s great epics like The Ten Commandments (’23) in scope & splendor, but outdid him in their masses of humanity. Mary Pickford starred in & produced Lubitsch’s first American movie, Rosita (’23), a film she professed to have never liked & at one point tried to destroy all remaining prints. After Rosita, however, Lubitsch returned to his true love & made 2 of the best examples of romantic comedies in the mid ‘20’s with The Marriage Circle (’24) & Lady Windermere’s Fan (’25). Although more serious than his later work both film build on the Lubitsch style evident in his earlier work by more fully taking advantage of silent films’ strength, that is the faces of the actors. Since Lubitsch disliked title cards he worked to have the actors convey as much of the story as possible with gestures & looks, while simultaneously utilizing editing to emphasize & fill in what was missing, essentially drawing the viewers eyes around the frame where he wanted it. The genius of Lady Windermere, Lubitsch’s reworking of Oscar Wilde’s famous play, is that he didn’t use any of Wilde’s cleaver puns & verbal wit on the title cards, instead relying on the actors to convey the sly commentary of gender stereotypes & societal expectations through physical gestures &expression. The story of a wayward mother’s love for her adult daughter is an amusing story of marital mis-communication, suspicion, blackmail & self-sacrifice. It’s take on marriage, reflected in the seemingly happy couple, Lord & Lady Windermere, reflects the Victorian notion of chaste women under the influence of a benevolent provider husband. That Lady Windermere’s mother has chased love at the expense of her child sets the story in motion & illustrates the keen difference between expectations & reality in love & marriage. When Lady Windermere assumes her husband is having an affair, her first inclination is not to confront him, but to find a partner of her own. With damning evidence of her alleged indiscretion threated to be exposed her mother finally has a chance to redeem herself. The images are simple & mature, focusing on the primary actors & avoiding extraordinary melodrama & unnecessary flourishes. It is crisp and the acting is natural, reflecting Lubitsch’s emphasis on gesture & expression. His comedies were razor sharp & funny, never including a wasted line or gesture. Hitchcock called The Marriage Circle (’24) ‘pure cinema’, his highest compliment, & in talking about the same film, Renoir said “Lubitsch created the modern Hollywood. Whereas Lady Windermere’s Fan was more about mis-communication, there is no actual temptress wooing the husband, The Marriage Circle pointedly draws a distinction between a happy marriage & a miserable marriage & the intent to destroy both. The Marriage Circle is, for better or worse, a defense of the institution of marriage, which is a departure for Lubitsch because most of his films feature adultery and/or infidelity as a baseline for the plot. Here, however, marriage prevails over the deceit of Charlotte Braun’s (Florence Vidor) best friend Mizzi (Marie Provost) & the nefarious activities of Mizzi’s husband (Adolphe Menjou) to trap his wife in an affair. The Marriage Circle is often cited as the first silent film where the viewer actually sees the characters think, limiting the number of title cards & giving the film a more dynamic way of telling the story visually. The story was written by Paul Bern, who would later gain infamy as Jean Harlow’s husband who committed suicide shortly after they were married. Lubitsch himself remade The Marriage Circle as One Hour with You (’32), but with much less success. The Musicals (1929-1934) The advent of sound allowed Lubitsch to layer an additional element onto his palette of visual genius by having the characters speak, or in the case of his musicals, sing. His “Foxtrot Epidemic” sequence from The Oyster Princess essentially established how movie musicals would be shot, but it’s the seamless incorporation of the music into the fiber of the story that elevates Lubitsch’s musicals & puts them on an equal or higher footing than the more famous Warner Bros. musicals of the same period (Gold Diggers of ’33, 42nd Street, etc.) That Lubitsch was 2-3 years ahead of the Warner machine gave him the blank slate he needed to combine his daring sexual innuendo with cheeky songs to create choreographed mating dances. Using European or semi-European settings, Lubitsch was able to subvert more traditional, and puritanical, sexual customs usually found in Hollywood films of the time. That his main character in the 3 musicals featured on this list, played by Maurice Chevalier, had a rich French accent further extended his ability to create double & triple entendres by including a wink and a nod. The opening sequence in The Smiling Lieutenant (’31), for instance, “L’Amour in the Army” has a mischievous Chevalier bragging about his conquests as a soldier, including giving the girls “a rat-ta-tat-tat” in an overtly sexual rhythm. Later, after the naive Princess Anna (Miriam Hopkins) intercepts a wink meant for Chevalier’s Lieutenant Niki’s true love Franzi (Claudette Colbert), Chevalier explains the coded sexual messages when he tells her “When we like someone, we smile. When we want to do something about it, we wink.” In typical Lubitsch fashion there is a love triangle that needs to be worked out & Lubitsch, screenwriter Samson Raphelson & song writers Clifford Grey & Oscar Straus create the most salacious song in “Jazz Up your Lingerie.” As Franzi realizes Niki will end up with the sheltered Princess, she instructs Anna not just how to sexy up her underwear, but also how to please a man once the underwear comes off. It’s a daring song that both characters perform in lingerie, but it sums up Lubitsch’s take on sexual freedom & gives a clear insight into the director’s willingness to give that freedom to women. If there is one unfortunate element of The Smiling Lieutenant it is that Franzi must forego happiness so that Anna can be liberated, but Lubitsch would solve the issue of a menage a troi a couple of years later in Design For Living. Everything else about the film is perfection, however, with the script constantly delivering amazing one-liners, a wonderful commentary on marriage (‘for 3,000 years philosophers have been trying to figure that out”) & brilliant performances from all three leads. The Love Parade (’29), the earliest of Lubitsch’s musicals on this list, focuses on choice & duty, wrapped in another menage a troi in a make-believe European country. Count Alfred (Chevalier) has been caught in one too many scandals in Paris, including bedding the ambassador’s wife, so he is recalled to the capital of Sylvania at the behest of the Queen. As he sings the wistful “Paris, Stay the Same” Alfred lets loose a little of what got him into trouble when he sings “…with you each night meant, the thrill of excitement” as Lubitsch cuts to multiple shots of scantily clad flappers toasting champagne & shooting come hither looks. Once ensconced in the palace back in Sylvania Alfred by no means plans to chasten his sexual appetite, even promising the young, single & beautiful queen that “I’ll do anything & everything to please the Queen. If you want me to be good. I’ll be good. If you want me to be bad. I’ll be bad.” Lubitsch & lyricist Clifford Gray can get away with any & every inuendo because its set to a jaunty rhythm, but when the Queen forces marriage & the end of his freewheeling bachelor days, Alfred initially balks. Jennette Mac Donald plays Queen Louise, in her first of many musicals for Paramount over the next decade, as another in a long line of knowing, smart & independent women at the heart of Lubitsch’s films. She understands Alfred’s playboy reputation, but she’s smart enough to have him see that her love is worth any sacrifice of assortment in lovers. If The Love Parade was the beginning of Lubitsch’s musicals & The Smiling Lieutenant was the pinnacle, than the culmination was The Merry Widow (’34), Lubitsch’s take on the 1905 Operetta by Franz Lahar. The story of an anguished county’s desire to hold its wealthiest taxpayer in check by finding her a suitable husband. Of course, the bumbling government is able to send Prince Danilo (Chevelier), once again cast a playboy & rascal, to secure Madame Sonia’s (MacDonald) hand in marriage. Danillo opens the film singing “Girls, Girls, Girls” as he marches through the streets being waived into the homes of countless maidens, both married and single, so it’s really only inevitable that Sonia eventually fall for him. That it’s not as easy as planned makes for an enjoyable romp filled with Chevalier’s leering, winking & preening Prince counterbalanced by the pragmatic & practical Madame Sonia. Love always finds a way in a Lubitsch musical, but it’s the journey that makes them all so enjoyable. The Comedies The ‘Lubitsch Touch’ is never more evident than in Lubitsch’s Paramount comedies of the 1930’s. While he was able to hone his visual comedy in his silent films & his knowing sexual inuendo in his musicals, the comedies provided the platform to add a verbal complexity to his sly & witty undermining of social & sexual taboos. In the later 2 on this list, Ninotchka (’39) & To Be or Not to Be (’42) Lubitsch was forced by the production code to eliminate many of his sexual references, so he turned to poking fun at politics & social standards. It’s no coincidence that Lubitsch struggled after the implementation of the Production Code in 1934, with only 2 of his 10 best released after its implementation, because the Code removed ‘adult reality’ from both scripts & stories so as to not offend the easily offended. Comedy is at the core of everything Lubitsch stood for & what he put on film & the code forced him to be more creative & subversive, in both cases going ‘over the top’ to make his point & create lasting humor. When Niniotchka (’39) was released it was sold to the world as ‘Garbo laughs’ in reference to Greta Garbo’s first comedy. She plays a stern & humorless Soviet bureaucrat tasked with bringing 3 comrades to heel & recover the jewels of the former aristocracy. Melvyn Douglas plays a gigolo of sorts who seduces Ninotchka to keep the jewels, but ends up falling in love with the ever melting Bolshevik. Lubitsch & co-screenwriters Charles Brackett & Billy Wilder weave together repeated references to the hypocritical nature of the Russian Revolution & communist society. When questioned about the political purges in Russia, Ninontchka responds, there’s going to be fewer, but better Russians.” As she slowly warms to Douglas’ charms, however, the comedy turns towards her awakening sexuality in an exchange like this: Ninotchka: “You’re very talkative.” (He kisses her.) Count Leon (Douglas): “Was that talkative?” Ninotchka: “No, that was very restful. Do it again.” The line readings by Garbo play on her personae of cold indifference, but are given a playful tone through the smartness of the language. At the same time Lubitsch is attacking social hypocrisy, he is undermining a star’s calculated public image & making the audience laugh both at & with Garbo, all while she’s in on the joke. Of course, no mention of Ninotchka would be complete without a passing reference to the wonderful comical work done by Sig Ruman, Felix Bressert, & Alexander Granach as comrades Iranoff, Buljanof, & Kopalski who immediate set about to undermine all that communism stands for as they take advantage of everything Paris has to offer! To Be or Not to Be (’42) uses the German invasion of Poland as the backdrop to a riotous comedy. A polish theater company, led by the hammy Josef Tura (Jack Benny) are crafting a new play, “Gestapo,” a full on send up of the Nazi’s. He becomes distracted by what he perceives as an affair with wife Maria (Carole Lombard) is having with a Polish resistance pilot. What transpires is pure mayhem as the theater company impersonates the Nazi’s as they arrive in Poland in preparation for Hitler’s arrival. Lombard received top billing, in a film that was released after her tragic death in a plane crash, but Lubitsch placated Benny by telling him “but you have all the lines.” In what amounted to a career defining role for Benny, his Josef Tura allows the radio & future TV star to exaggerate his normal ham-handed performance style with a knowing wink. If ever one film could be slipped in to the filmography of another, the mayhem of To Be or Not to Be would look right at home as a Preston Sturges film (Not to diminish the individuality of either film maker, but there is no better descriptor of the absolute lunacy of this plot). Finally, there are the 2 gems in Lubitsch’s filmography that stand among the greatest & most sophisticated comedies of all-time, Trouble in Paradise (’32) & Design For Living (’33). Both films deal with love triangles unlike any other in film history. In Trouble in Paradise master jewel thief Gaston Monescu (Herbert Marshal) partners with pickpocket Lily (Miriam Hopkins) to fleece perfume heiress Madame Mariette Colet (Kay Francis), but love get in the way as first Lily, then Gaston & finally Madame Colet each falls in love. Design for Living again stars Hopkins, but this time she is the fulcrum between down & out artists Tom Chambers (Fredric March) & George Curtis (Gary Cooper). As the men’s bohemian existence is blown up by the beautiful reporter a sexual triangle develops just as in Trouble in Paradise, but made a year later, Lubitsch pushes the boundary even further.

Trouble in Paradise is generally viewed as Lubitsch’s masterpiece & one of the greatest comedies of all time. The scene where Gaston & Lily have a quiet dinner , while they pilfer & probe each other, is a masterwork of inuendo, slight of hand & sexual mischief. Hopkins is luminous & Francis never better, with each delivering a wonderful vulnerability beneath their steely veneer. The film builds on one clever scene after another as the thieves ingratiate themselves into Colet’s life, while simultaneously falling in love with Gaston. If Lubitsch didn’t keep things so light the viewer might actually start to feel sorry for Colet, but it’s really a beautiful balance between all three that keeps the triangle intact throughout. Supporting characters, the Major (Charles Ruggles) & Francois Filiba (Edward Everett Horton), bring added humor as suitors to Madame Colet, but it’s really the trio that casts a spell over any viewer. It’s a marvel throughout & at only 88 minutes there is not one wasted gesture, word or shot in the entire film. It is perfection. Just one year later, however, Lubitsch created what I think is his masterpiece & one of my 10 favorite films of all time, Design for Living. While Lubitsch exploited the Pre-Code Era to more overtly trumpet his European version of open sexuality, he always did so in a very classy fashion. With Design for Living, however, he opened up that inuendo to include overt references to a threesome between 3 very bankable Hollywood stars. Hopkins’ Gilda Farrell turns the tables on the traditional male role of morally ambiguous sexual morality, by opening admitting that she is in love with & sleeping with both men. Gilda plainly explains the difference in her character & any other movie character of the era: “A thing happened to me that usually happens to men. You see, a man can meet two, three or four women & fall in love with all of them, and then, by a process of interesting elimination, he is able to decide which he prefers. But a woman must decide purely on instinct, guesswork, if she wants to be considered nice.” She is nice & she’s definitely a woman, so Lubitsch has it both ways & it’s entirely plausible. In fact, after shaking hands in a gentlemen’s agreement between the three, Gilda admits, “It’s true we had a gentlemen’s agreement, but unfortunately, I am no gentleman” making it plain the world is flipped upside down & she intends to woo & have sex with both parties. Of course in Lubitsch’s world the men are the ones slow to embrace love by any terms & the final scene seals the deal, creating one of the greatest examples of Pre-Code filmmaking. If Trouble in Paradise if perfection, Design for Living is perfection plus 10. Lubitsch was never a box office champion with his American films, but among hardcore film fans he ranks among the greatest creators of all time. He brought a European sensibility to his American films that pushed the medium to be smarter, first as a visual stylist in the silent era & then doubling down on that visual style by adding razor sharp dialogue. The “Lubitsch Touch” is tangible in all his films & it represents his belief that the audience can intelligently determine what the adults in his films are doing. He didn’t so much beat people over the head with sex, but coaxed them, romanced them & seduced them. It’s what makes his film so enjoyable today & gives them a timelessness. The dialogue is still smart, the plots move along very briskly & the characters and setting are stunningly beautiful.

0 Comments

|

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed