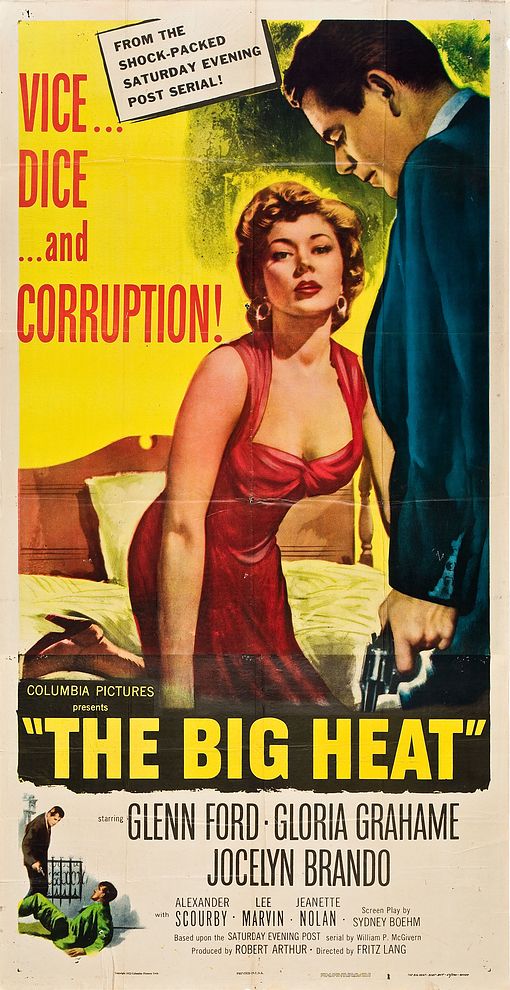

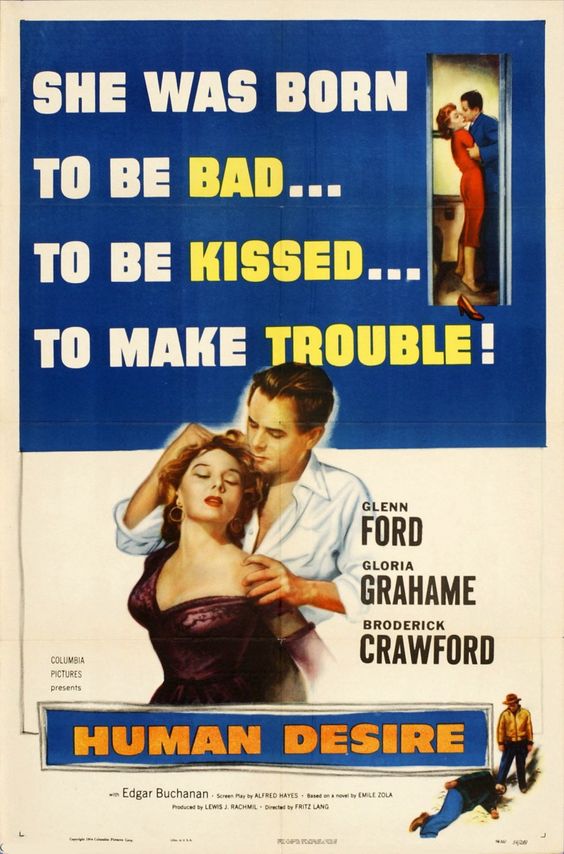

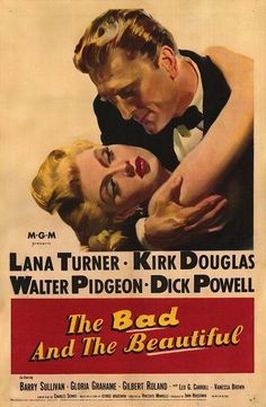

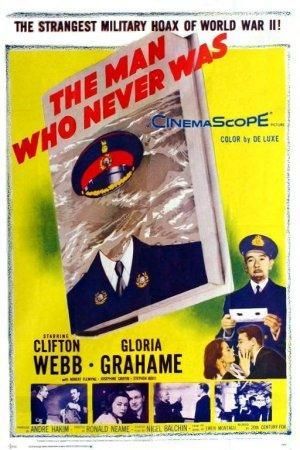

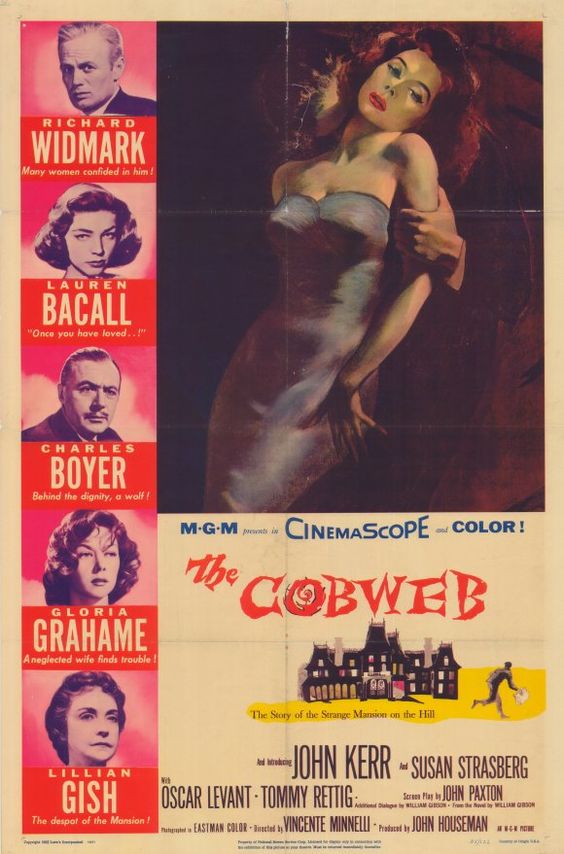

The Rationale: Although primarily known for her supporting work, Gloria Grahame proved that she was more than capable of leading roles in films like In a Lonely Place & Human Desire. From her first significant role as Violet in It’s a Wonderful Life Grahame was very good at getting noticed. Quite often she didn’t have to have much screen time to create memorable characters, in fact winning a Best Supporting Actress Academy Award for about 9 minutes of screen time in The Bad & the Beautiful. Sometimes remembered as one of the preeminent actresses of the Film Noir era (roughly 1940-58), Grahame’s career ebbed & flowed until her death from cancer in 1981 at the age of 57. She was also famous for her often colorful personal life that included a marriage to director Nicholas Ray (In a Lonely Place) and later to Ray’s son Anthony. She was above all, however, a dynamic actress who brought warmth to cold & calculating characters, while often projecting steely resolve to hide tender souls. Her performances were sexy, humorous and richly crafted and she is too often overlooked for as good an actress as she was. In a Lonely Place, directed by Ray while married to Grahame, offers performances as rich as any in film history. Grahame plays opposite Humphrey Bogart, in perhaps his greatest performance, as a neighbor who offers his alibi against a murder charge. When the couple falls in love, while the true fate of the murder victim is still in question, doubt & suspicion threaten the couple’s happiness. Grahame’s performance is at once tender, strong, sexy & confident, offering a peak into a stormy marriage as a secondary layer while hers and Ray’s marriage dissolved during filming. The famous line from the film “I was born when she kissed me. I died when she left me. I lived a few weeks while she loved me” is apropos of both the film’s story line & the marriage. A snide look at the Hollywood Blacklist, as well as Hollywood itself (“you’re nothing but a popcorn salesman”) In a Lonely Place is not only Grahame’s greatest & most complete performance, but it is one the greatest films of the 1950’s. As noted, Grahame was a staple in the Noir cannon & her 2 films with Fritz Lang stand as pillars of iconic characterizations. In The Big Heat she plays the mobsters moll, normally a bit & insignificant roll in Noir, but turns she it into the pivotal and most memorable performance in the film. In Human Desire, she is the Femme Fatale, complicit in her husband’s killing of her childhood abuser who then tries to enlist her lover in the killing of her husband. What is most wonderful about both performances is that while the scripts morph the stock characters against type, it is Grahame who injects them with soul. Her portrayal of Debby Marsh in The Big Heat is a brilliant mix of offhand sarcasm, fatalist braggadocio & pitiable insecurity. The scene in her hotel room with co-star Glen Ford wonderfully captures the character & Grahame’s acting in one quick flash. She initially plays the coquettish flirt, offering Ford’s Bannion the only thing she thinks has value, only to shift to a wounded and hurt child when he rejects her. Grahame offers depth and honesty in the entire scene as a testament to her chops. Her death scene also illustrates her ability to hold the viewer’s attention in moments of great intimacy and vulnerability. Vicki Buckley, from Human Desire, while not a sympathetic character like March, offers Grahame just as many opportunities to showcase her skills. She is cold, calculating and manipulative in equal parts towards her husband, while sugary sweet and genuinely sincere, at times, with Ford’s Jeff Warren. While she witnesses her husband’s killing of her former abuser there is clear mixture of horror, fear & exhilaration on Grahame’s face. When meeting Warren moments later, she shifts to seductress ever so easily, reinforcing Grahame’s chameleon like presence & finely honed femme fatale persona. Warren is clearly putty in her hands and it only takes a couple of carefully raised eyebrows to have him considering killing her brutish husband. Director Lang is considered a Noir master largely on the performances of his femme fate’s & Grahame adds strongly to the characterizations of Joan Bennett in Scarlett Street (’45) & The Woman in the Window (’44). The next 3 films represent Gloria Grahame’s strength, but also the weakness of her career. She was so good in smaller roles, like those represented by The Bad & the Beautiful, The Man Who Never Was & Crossfire, that you wish for more, but leave satisfied with what you’ve just witnessed. She won the Best Supporting Actress Award for Bad & Beautiful for all of 9 minutes on screen; she had only 2 significant scenes in Man Who Never Was, but was arguably the best thing about the movie, & was a smaller player in Crossfire, yet received an Oscar nomination for her performance. In each performance she is very different, but Gloria still shines through. In The Man Who Never Was her 2 scenes, one composing the letter to a fictitious soldier that mirrors her feelings towards her fiancé & the second convincing the German spy the dead man really existed are each tour de force performance pieces & Grahame carries them off flawlessly. Both rely on her voice & her face to capture her love & despair. In Bad & Beautiful Grahame is a southern belle, married to a stuffy writer/college professor who expresses her sexual frustration in small ways, then large ways, but both as a form of rebellion against ‘50’s domesticity. She is witty when called upon, sexual when she wants to be and stupid when she can least afford to be, but she is unlike anything else in Grahame’s career (The Cobweb’s doctor’s wife would be the closest, but with more inherent selfishness). While the Oscar may have been a reflection of earlier performances, Grahame demands the viewer’s attention in every scene she appears and shows her powerhouse capabilities in each. Finally, it is her ability to create a 3 dimensional person out of very little that made the performance memorable and award worthy. If Grahame was prim & proper on the surface in The Bad & the Beautiful, she is cheap and tawdry in Crossfire, playing a B girl in a cheap saloon. As in In a Lonely Place she has the potential to provide an alibi for an accused murderer, but in Crossfire she cannot do so because she doesn’t come home while he waits for her. When confronted by the police to confirm the alibi she is cynical & defensive, snapping “I don’t like cops”, before ultimately admitting that she was “working” at the time of the murder & couldn’t help. At the same time, however, she confirms the accused story about meeting at the dancehall/saloon, wistfully recalling she “…could have cooked him something and we could have talked” if he had waited for her at the apartment. The dichotomy of the scene presents these opposing emotions as natural in Grahame’s character and strengthens the performance, albeit her last appearance in the picture. Sudden Fear is definitely Joan Crawford’s movie. As is always the case, Crawford dominates every scene she plays, often relegating the other actors to the shadows, if not erasing their presence altogether. What I like about Grahame’s character in this film, however, is that she is completely separated from Crawford, never appearing on screen with her. This allows a wonderful cat & mouse game between the cuckolded wife (Crawford) & the mistress (Grahame), with the duplicitous husband (Jack Palance) being bounced back & forth. At different times, both women hold the power, but Grahame’s portrayal is cool & calculating, while Crawford’s is scattered & neurotic, perfectly reflecting the early ‘50’s ethos of ‘wife’ & Femme Fatale. Grahame is at home as the gold digging con artist, unaware & unrepentant in her greed, a reflection back to her characters in Crossfire & Human Desire, but this time without a soul.

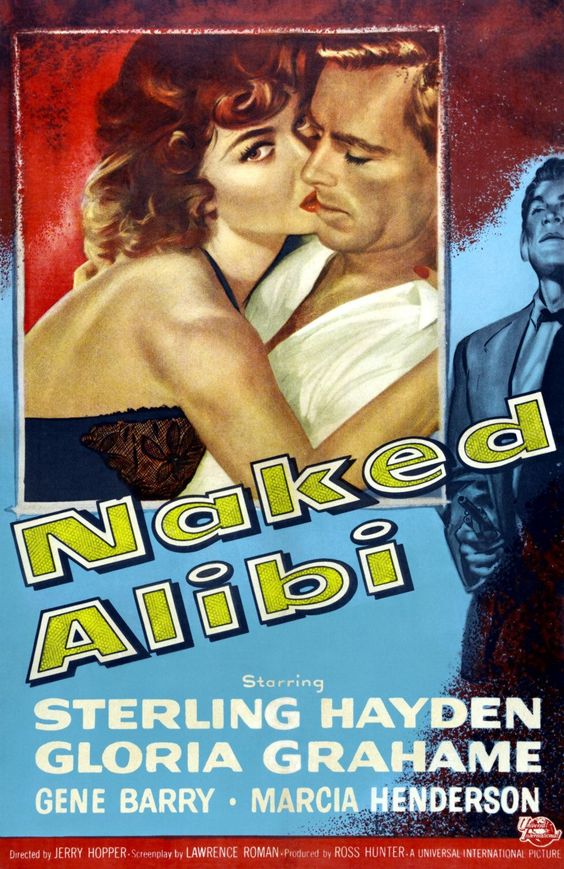

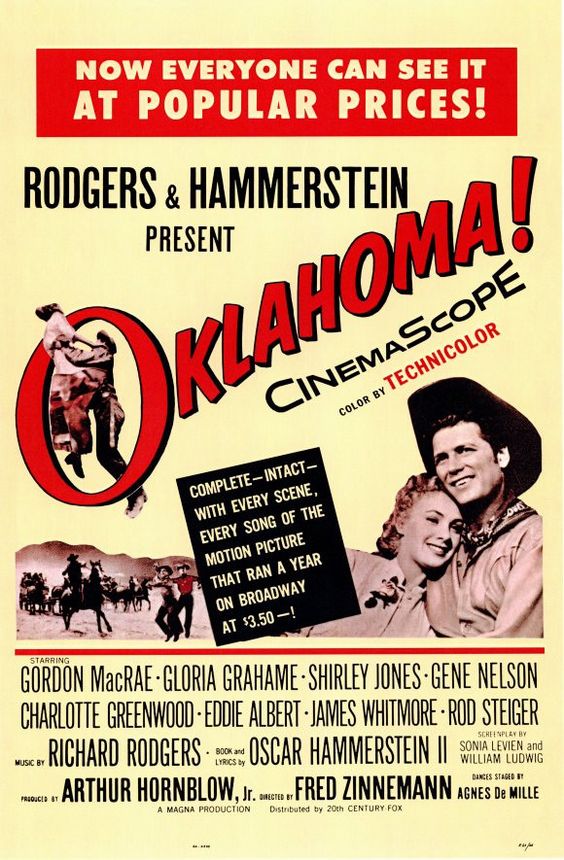

Grahame’s characters in Naked Alibi & The Big Heat have more than a little in common. Both are mobster’s molls & both betray their boyfriends for a well-meaning cop whom they also fall in love with, but their differences & the differences in the movies make the characters nothing alike. While The Big Heat exists in a middle class milieu, Naked Alibi lives in the seedy part of a border town & Grahame’s Marianna is not a kept woman, but a cheap nightclub singer. She is more streetwise than sarcastic & her love for the cop seems borne more out of similarity than desperation. Finally, there is Oklahoma, where Grahame further expands her repertoire to include comic relief. Her simpleton portrayal of Ado Annie Carnes is at once funny, but still filled with the animal sexuality that punctuates her best Noir performances. When she sings “I’m just a girl who can’t say no” it just seems like an internal monologue from prior performances externalized in song! When she also tells her betrothed, Will Parker (Gene Nelson), that she “never thinks of no one less they with me” it also harkens back to many of her earlier characters & their willingness to cheat on or manipulate. It’s a funny performance, but like everything else she does Grahame gives it more than surface to make it bigger than it would have been on paper…or in previous stage performances. With a few exceptions, Gloria Grahame was relegated to TV work a mere 14 years after she first gained notice on the big screen as Violet in It’s a Wonderful Life, a victim of personal insecurities and the ever present plight of the aging actress in 1950’s Hollywood. During that time, however, she appeared in no fewer than 4 all-time classics, received 2 Academy Award nominations with 1 win & established a persona that would stay with her well beyond her death in 1981. While she enjoyed stage work until her death, she was best suited to the big screen where her subtlety in style & quiet movement could best be exploited and captured. Her Top10, captured here, represent both her best performances and the breadth of her talent.

5 Comments

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

- Anatomy of a Murder Notes

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed