|

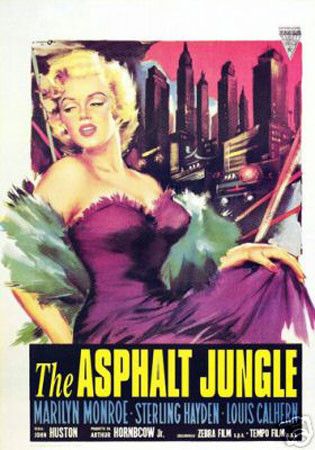

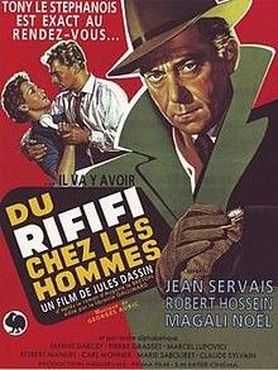

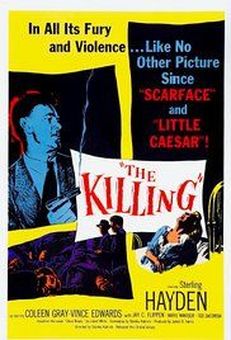

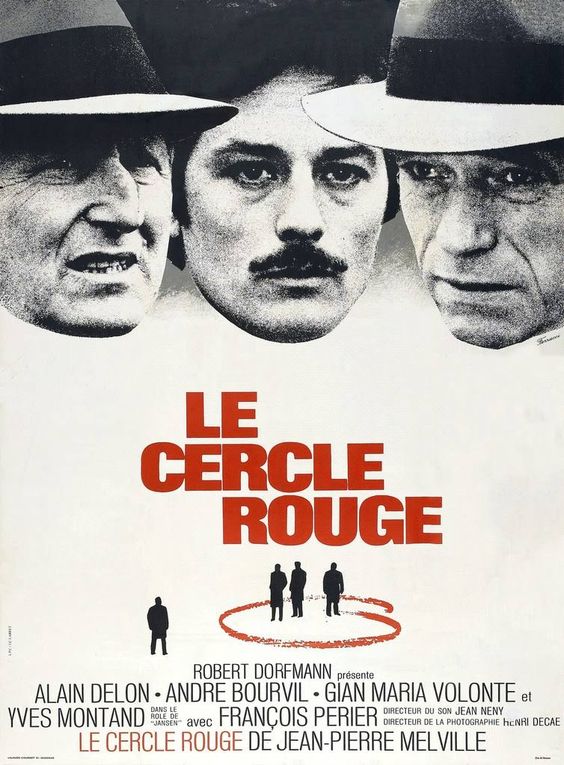

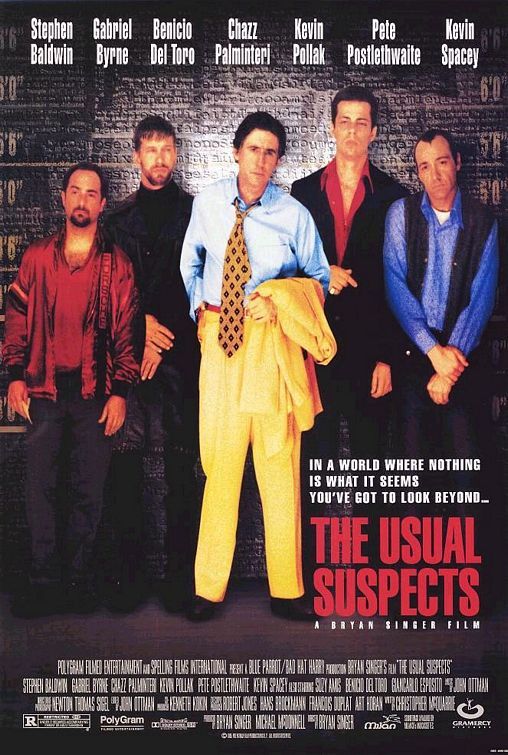

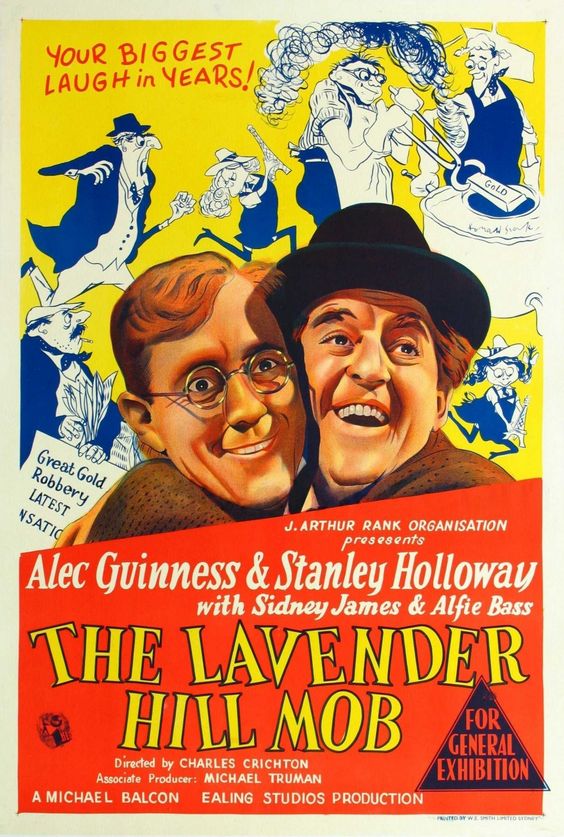

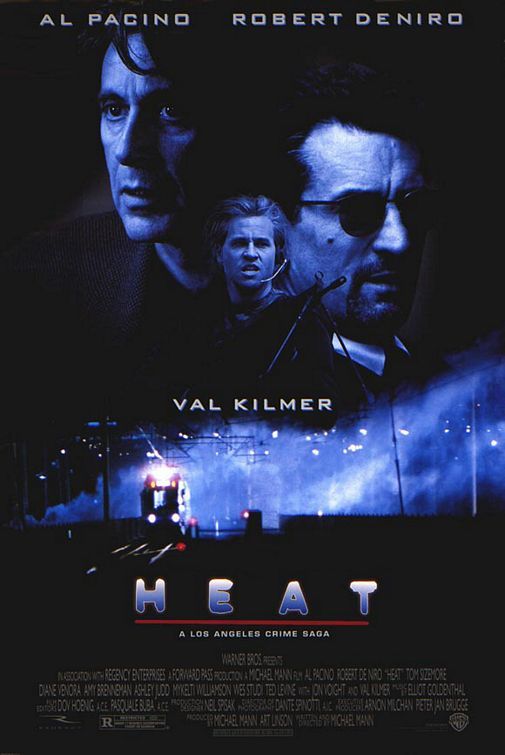

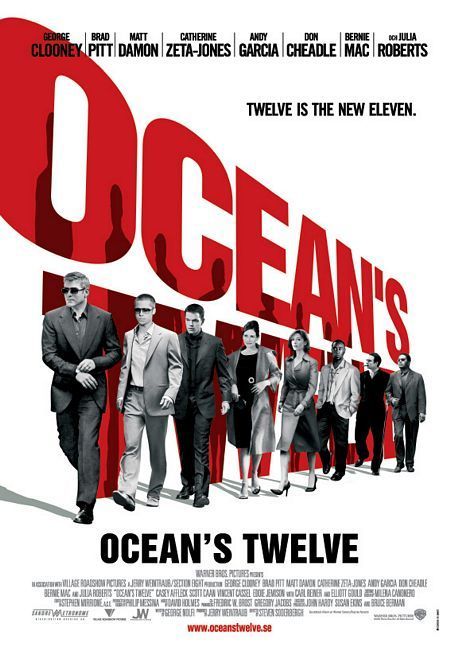

The Rationale: Every good heist film has 3 things in common: the set-up, the execution and the aftermath. Where each film places the emphasis is what creates the intrigue and the excelence. A film like A Fish Called Wanda (’88 M. Crichton), for instance is all aftermath, while Heat (’95 M. Mann) is mostly set up. Rififi (’55 J. Dassin) plays it right down the middle, with the heist itself the literal centerpiece of the film. Each element obviously has many nuances, which makes heist movies some of the most interesting & intricately plotted in all moviedom. The set-up generally includes the assembly of the gang and an outline of the robbery. Characters may be left sketchy or crudely shown, only to reveal their true nature later on. Similarly, the heist may be broadly painted to ensure more intricate plot points as it unfolds. The heist itself, when well done is often executed in complete silence and can be rendered in real time or compressed to show only the highlights. The aftermath, on the other hand, is often a jumble of betrayal, revelations or just plain bad luck. At its core, a great heist film creates & maintains a high level of tension throughout, casts its heroes and villains in equal shades of gray & never allows the viewer to know much more than the characters themselves. To level the claim of cinematic perfection is a tall order to place on a single film, but The Asphalt Jungle is as close to perfection as they come. In addition to bubbling to the top of any Best Noir Films list, The Asphalt Jungle helped create a template for the heist film that has been ripped off, manipulated and enhanced for more than 50 years. Starting with the amazing opening scene of Dix Handley (Sterling Hayden) avoiding the police in an urban wasteland and continuing until its sad conclusion in the rolling hills of Kentucky, The Asphalt Jungle is concise perfection. The greed and deception that undoes the gang is sewn from the beginning, as each player sizes up the others, then sets up their own selfish play. Only Dix approaches the ‘caper’ for what it is, a means to an end; a return to a simpler and happier time. W.R. Burnett’s novel & John Huston & Ben Maddow’s script, combined with Huston’s sharp eye for claustrophobic interiors & desolate exteriors, create a short hand of desperation and exposition. In what would be commonplace later, The Asphalt Jungle begins with the assembly of a team for a jewel heist by a just released from prison criminal mastermind. Characters are chosen by type: a safe cracker, a getaway driver, a hooligan. Even Doc Riedenscheider’s introduction foreshadows his ultimate undoing and each of the others brings both strengths and weaknesses. As they assemble, it is the wild card, in this case the fence, that adds friction and uncertainty to “a sure thing,” but as the plan is laid out it naturally seems foolproof. Huston brilliantly, and without dialogue, renders the robbery itself as a masterstroke of concise movement & choreographed signs between the criminals. There are moments of high anxiety and jubilation, but as became a bell weather for the heist film, there is fate and luck, which ultimately directly or indirectly leads to success or failure. Typically, what at first seems minor becomes important & what seems impossible becomes inevitable and leads to the aftermath, that is complete with double-crossing, arrests and, of course, death. The Asphalt Jungle perfectly constructs and executes the heist film, creates man of its architypes, but at its center it is the heist itself that is the jewel of this film. Jules Dassin was known for making gritty American Noir films like Brute Force (’47), Naked City (’48) & Thieves’ Highway (’49) before he was exiled to Europe in the wake of the red scare brought about by the House Un-American Activities Committee. It was perhaps while in Europe that he arguably made his 2 best films, Night & the City (’50) and the #2 title on our list Rififi (’55). Made in France after a long layoff, Dassin crafts a low key, but high tension heist of a jewelry store. Led, as in The Asphalt Jungle, by an ex-con, Rififi takes the center third of the movie walking the viewer through the 33 minute crime in nearly complete silence. Taking what Huston had done with the robbery portion of his film, Dassin amps up the tension and the delicate execution of the crime into near ballet-like elegance. The meticulous attention to each detail of the plan, from the signal whistle from one thief to another, to the assembly of the specific tools of the trade are balanced by Dassin’s subtle images highlighted by a sweeping flashlight across a darkened room and an overhead shot of team as they dismantle the floor. Nothing is wasted even the dust & debris, which is ingeniously & elegantly captured. Rififi also helps expand the world in which the heist film exists by placing the characters at the edges of society, in the underworld that harkens back to the gangsters films of the ‘30’s. Quiet conversations held in public, but under breadth, exaggerate the conspiratorial nature of the heist film & Dassin plays them very low key, especially in the performance of Jean Servais as the haggard ex-con. His world weariness is, in fact, a precursor to Sterling Hayden’s portrayal in the next film on our list, The Killing. Stanley Kubrick’s early masterwork, The Killing (’56) boldly manipulates time in its presentation of a racetrack robbery. Jerking forward, then doubling back to reveal more about the characters, their intentions and ultimately their motives, The Killing is a precursor to such time altering mimics as Pulp Fiction (’94 Tarantino) & Memento (’00 Nolan). Sterling Hayden once again stars, this time as caper mastermind Johnny Clay, and he does not disappoint, in turns menacing, empathetic & romantic, Clay clearly has the fates working against him, but his sincere effort casts him as one of Hayden’s finest performances. As is typical, the assemblage of the crew marks each participant’s flaws and hints at their individual downfall, but Kubrick wisely leaves the fate of the caper to luck, chance and finally fate. Two things in particular elevate The Killing from standard B fair of the time: the wonderful execution of the heist itself, even as the timeline doubles back on itself, and the ever increasing anxiety in the viewer who often assumes what is to happen, but is often shaken and surprising with the manipulation of those double backs! Co-written by Kubrick & writer Jim Thompson, The Killing crackles with sharp dialogue and crisp black & white images & features one of the best Noir casts ever assembled. No list of the best Heist films could be complete with Jean-Pierre Melville (Bob le Flambeur ’56 & Le Samourai ’67), the French master of criminality on film. Le Cercle Rouge (’70) was his penultimate directorial effort, but certainly one of his best (sadly, I have not seen Bob le Flambeur ‘56 or Le Doulos ’63). Centered around 2 stellar performances by Alain Delon & Yves Montand, Le Cercle Rouge adds yet another unique element to the heist picture, the relationship between the cops & the robbers, even going so far as to have Montand’s character an alcoholic ex-cop. The single-minded police commissioner Mattai (Andre Bourvil) matches the meticulous nature of the criminals as they plan & execute their crime & he doggedly tracks the fugitive among them. The crime itself, done in silence, is a masterstroke of sharp angles & lines, from the labyrinthine building they break into, the infrared security system they foil to the patience in their escape. In fact, Melville actually referred to this film “a sort of digest of all the thriller-type I have made previously” and realized it would be difficult to execute. There are elements of homage to Asphalt Jungle & Rififi, but Le Cercle Rouge is one of many heist films that build upon the foundation to create a symphony all their own. The next 2 films, The Usual Suspects (’92) & Reservoir Dogs (’92) visually have little in common, but both add unique characteristics to the Heist sub-genre, while at the same time building & borrowing from what came before. The Usual Suspects is sleek & slick as much as Reservoir Dogs is gritty & monochromatic, with the periodic splash of deep blood red, but they both wonderfully play with the traditional linear storytelling device, like The Killing on steroids. One need only consider the palette of “the line-ups” that begin both films to illustrate their storytelling design; Usual Suspects characters wear bright, primary colors (canary yellow & deep blood red), while in Reservoir Dogs they are specifically clad in black suits with white shirts, monochromatic. The Usual Suspects, then, crafts a story, told by a seemingly reliable witness, that is both fantastical and terrifying, until the final unraveling in the final shots. Reservoir Dogs, on the other hand, moves back & forth re-crafting the viewers understanding of what came before, while offering character markers that play out later. In both films, the heist is the enter piece of the story, but it is in the telling that the details emerge, instead of in the showing as in earlier examples on this list. Together, these two offer the best of the modern example of the heist film, with a bit of self-reflexive panache, adding serpentine storytelling and plot maneuvering to keep the viewer off balance and increase tension and suspense. Unique among the list of ten is The Lavender Hill Mob, a British comedy that involves the stealing of gold by an outlandish group of misfits. Presented as a well-planned comedy of errors and cunning ingenuity, Lavender Hill Mob is both funny and cleaver. The mobs leader, Holland (Alec Guiness), is a mild mannered & subservient bank employee who longs to escape his soul crushing day to day existence. His plan is foolproof because he is the least likely criminal mastermind, but he has no way of disposing of the gold once he steals it. A new found friend, with a handy business solves his problem and the crime is executed, the gold transformed and shipped out of the country, but at every turn, and especially in Paris, there is madcap mayhem until the final escape. An added bonus to Lavender Hill Mob is the clever framing device that brings the whole story home as Holland tells the story of the caper. Similar in tone, while not an outright comedy, is The Italian Job (’69), a cleaver cat & mouse game set in the streets of Turin and the surrounding mountains. Michael Caine stars as Charlie Croker, a just released thief who devises the ‘big job’ that will be his ticket to the good life (or better life, if his sex life is any indication of pre-prison). Co-starring are a fleet of mini-Cooper, driven by a team of crooks, as they create and then race through and around a massive traffic jam in the Italian city. Benny Hill plays a computer programming wiz who sets the traffic jam in motion, appearing as a forerunner to his 70’s television show lascivious troublemaker. The intricate workings of the Coopers in the city are a joy to behold, while the climactic conclusion in the Alps literally leaves the crooks hanging by a thread! A special treat is the performance by Noel Coward and the shared scene between him & Caine in a prison bathroom. The final 2 films are modern interpretations of the heist film, executed by stylish autuers. Michael Mann's elegant and slick Heat is a testament to style & substance merging into something greater. Mann's Los Angeles is reflected in deep rich colors and shimmering neon lights, but the crux of the story is the cat & mouse game between a hyper-driven cop (Pacino) & a calculating & unfeeling criminal (DeNiro). They both live by the code of their profession, but the thrill is too great for either of them to bend to other, even as the film tumbles towards a gun battle showdown. Heat is cool in every respect and the precision of the heists are a joy to watch, but as is typical in the cannon of heist films, it is always luck, one loose cannon and/or the girl that befalls the captain of any crew. DeNiro represents the detached nature of the crimes, but it is Pacino that gives the film the propellant heat that drives it. Heat has a lot of style, but there is rich substance that creates a tense back and forth between the criminal and the cop. Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Twelve (’04), on the other hand, is a heist, wrapped within a heist, enveloped by a con. It’s also good, clean fun, which is clear in the performances of the all-star cast, led by Brad Pitt, George Clooney & Julia Roberts, who each poke fun at their public & professional persona. Don’t get me wrong, Ocean’s Twelve is all about style; the design is captured in warm golds, blues, greens & oranges, for instance & the entire look shimmers. Building from & riffing on Ocean’s 11 (’01), Soderbergh has the crew circle the globe to outsmart master thief Night Fox, while staying one step ahead from revenge minded Terry Bennedict. The stealing of a Faberge egg that is at the center of film, as are the other crimes, is only shown after the fact, muting the suspense, but amping up the style. The meticulous planning, in this case, is as important to show as the crime itself. Along with Lavender Hill Mob & The Italian Job, Ocean’s 12 has the most fun among the list, but doubles down on the panache.

There are a bunch of movies that have heists in them that I have purposely left off this list, including Criss Cross (’49), Snatch (’00), A Fish Called Wanda (’88) & The Thomas Crown Affair (’99), because the heist itself wasn’t the central defining element of the plot. In each of these 10 chosen, the heist is the thing, albeit with certain differences in focus & execution. In some it is the joy in the mechanics of the heist, in others the human element takes precedence and in still others it is the preparation. In all of the films, however, it is the gang itself, which is the building block of a successful heist film and these 10 have most dynamic gangs and they directly lead to inclusion as the Top 10 Best Heist Films.

0 Comments

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed