|

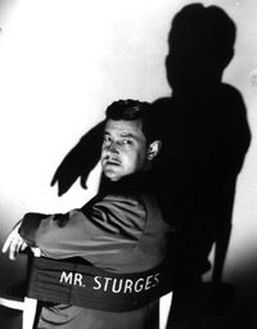

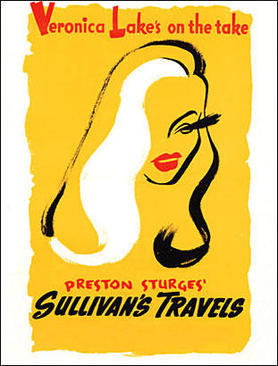

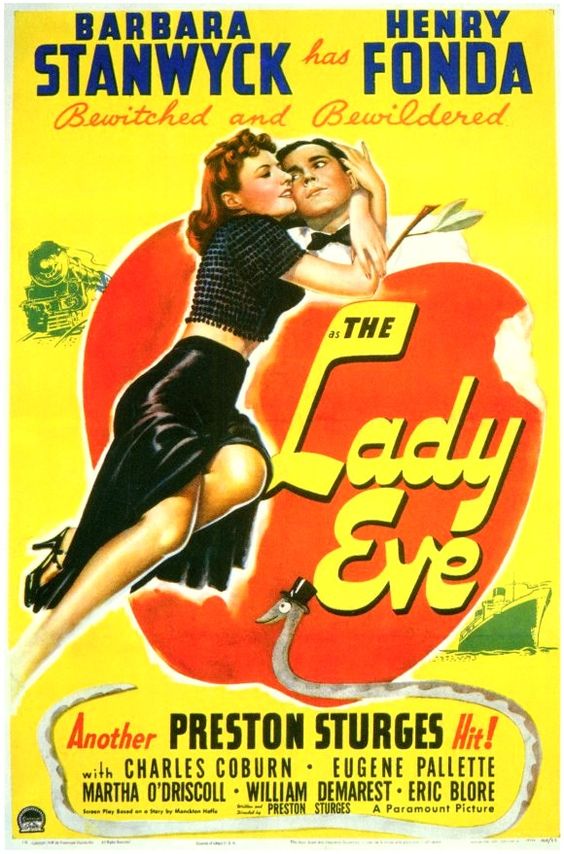

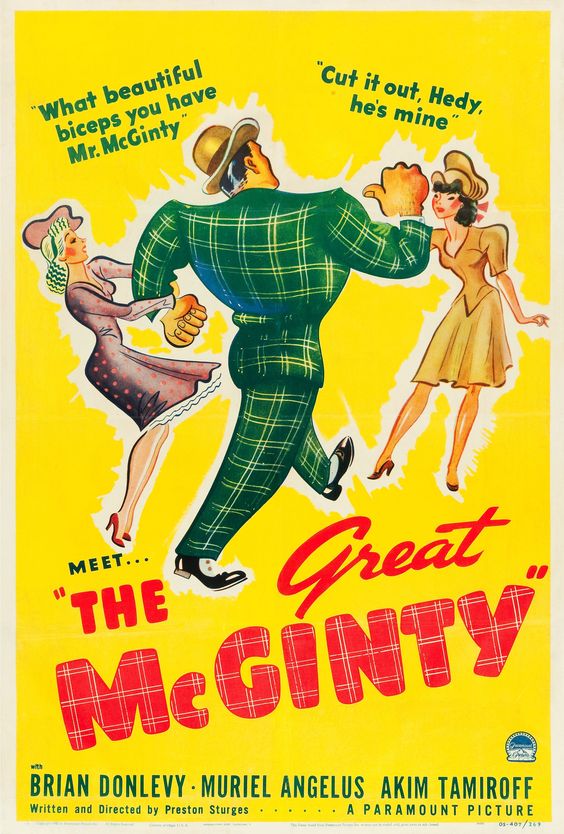

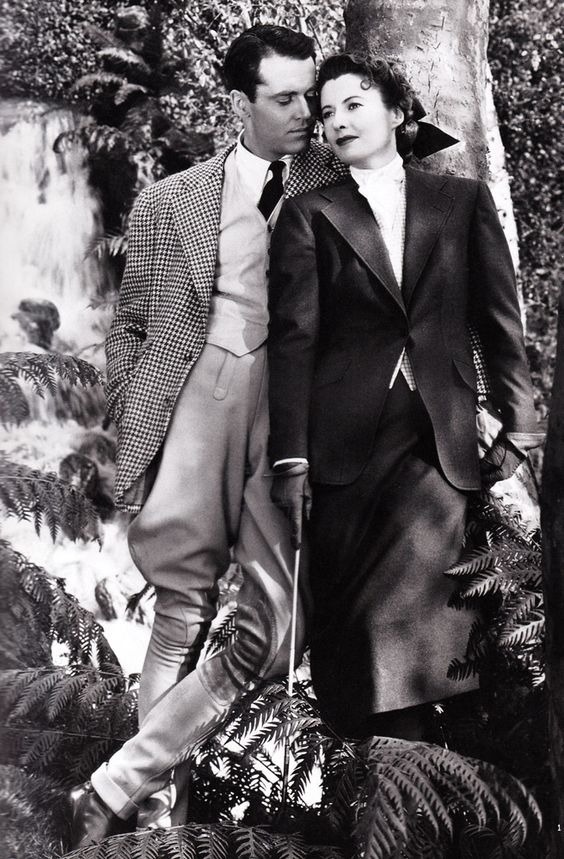

The Rationale: Preston Sturges wrote and directed perhaps the greatest 4 year span of creative output in Hollywood history. Beginning with The Great McGinty (’40) and right on through Hail the Conquering Hero (’44) the 8 films that Sturges created, 4 of which are full on comedy classics, represent the zenith of his career & the mantle for creative genius. Incredible, considering he is only credited with directing 12 films & writing an additional 10 more. Before his burst of creative genius Sturges was a struggling playwright who ended up with a staff writing job at Paramount. Sturges felt his earlier script for The Power & the Glory (’33) had been ruined by director William K. Howard & was bound & determined to not let that happen with The Great McGinty, a script he had been shopping around Hollywood for 7 years. He famously offered Paramount production chief William LeBaron his script for The Great McGinty for $1, provided Sturges could direct the film. With little to lose, LeBaron accepted and Sturges was off & running. Sturges’ feelings towards a screenplay (and the associated value of the screenwriter) can be easily summed up in a pitch he once made to Paramount chief Jesse Lasky, “Dialogue is the flavor of a talking picture. Mediocre speeches will ruin the story as sure a bad cooking will ruin good food. I believe good dialogue is the cheapest insurance a producer can buy. It makes good material magnificent & average material at least presentable.” (Curtis, p. 94) True to form, Sturges is a writer at heart, but able to transform his words into images that sparkle with wit & hilarity & ultimately elevate the words to genius & the films to classics. Starting at the mid-point of historic run is Sullivan’s Travels (’41), the film I feel is Sturges’ most complete and endearing. It is witty, of course, but at its core it is a love story about comedy and the ability to make people laugh. Sullivan’s realization in the third act could just as easily been Sturges’ awakening to the power of the movies; having always considered himself a playwright by trade & a screenwriter by necessity. Sullivan’s Travels tells the story of a frustrated movie director, who has grown tired of pumping out bland comedies (“Hey-Hey in the Hayloft”, “So Long Sarong” & “Ants in Your Plants of 1939” for instance) for the masses & instead dreams of making a picture than means something. Studio leadership humors his cross country hobo pilgrimage to find the soul of the movie going public. Along the way Sullivan (Joel McRea) meets fellow traveler Veronica Lake, disguised as a boy, and the 2 set off to discover the true meaning of suffering, only to finally understand that laughter is its own therapeutic balm. Sturges’ satiric take on Hollywood hypocrisy & condescension spares no one, from the moguls only concerned about their ‘asset’ Sullivan, to the director’s lofty illusions of making art versus commerce & finally to the starry-eyed young women who come to Hollywood dreaming of stardom. That Sullivan is finally brought low & made to realize the simple joy his commercial movies bring to those suffering the most is the revelation that balances the brilliance of Sullivan’s Travels. Sturges certainly bites the hand that feeds him, but its poignancy of the message, in all its simplicity, that lasts and makes it Sturges’ best. Not far behind in the ranking would be The Lady Eve (’41), as close a second place as any title on any list on this site! The raucous story of a father/daughter team of con-artists out to swindle a brilliant simpleton heir to a beer fortune before their ocean liner docks. Henry Fonda plays young Charles Pike, a snake expert & heir to the Pike’s Ale fortune, more comfortable with reptiles than humans, especially when they look & act like the beguiling Jean Harrington (Barbara Stanwyck). Harrington & her ‘father’ “The Colonel” (Charles Coburn)immediately set upon young Tom, but when Jean falls in love with him she lets him off the hook. Her disdain/love for Tom leads her into a second impersonation that only a Sturges script could sort out, while still holding onto a shred of plausibility. If ever a simpler visual charade were perpetrated on screen I’d love to see it because Jean/Lady Eve Sidwich don’t fool Muggsy (William Demarest) nor the audience, but Fonda’s Tom is just dense enough to buy it hook, line & sinker! Stanwyck’s beguiling Jean wraps poor Tom around her finger, twisting his hair, spinning his head in so many directions that he not only can’t see straight, he can’t even walk straight (Fonda’s only physical comedy that I can recall). Sturges uses the battle of the sexes to make clear that a book smart man is no match for a street smart woman. He fills the script with wonderful one liners like “let us be crooked, but never common” & “a moonlit deck is a woman’s business office,” but leaves his most cleaver writing to fill in the con-artists back story, whether real or imagined. The story of “Handsome Harry” alone is worth the price of admission, as Lady Eve’s life story is created from scratch, right before our eyes, but clearly from the twisted brain of Preston Sturges. The Palm Beach Story (’42) is the Sturges film that elevates his stock company into a symphony of comedic genius. The Ale & Quail Club, made up of Sturges’ regular crew of actors like Dewey Robinson, Robert Greig, Dewey Robinson & the exquisite William Demarest, creates such consistent mayhem throughout the picture that not only does it help to propel the screwball plot forward at breakneck speed, but amplifies the absurdity of the entire affair. While Sturges was never given credit as a fine technical director, his framing of chaos is always spot on & never better than in the cramped train cars packed full of Ale & Quail Club members falling all over one another. Strangely enough, however, the Ale & Quail Club is just the tip of the iceberg in this madcap story of mistaken identity, masquerade, marriage & divorce & finally, love. Claudette Colbert & Joel McCrea play a married couple forced into divorce through poverty who embark on a cross country cat & mouse chase. McCrea plays an idealistic inventor out to reimagine the world we live in, while Colbert is the realistic & romantic wife out to enable her husband’s wild plans, if only she could divorce him to find a sugar daddy to fund the dream! Without The Great McGinty (’40) there would likely be no Preston Sturges Top 10! The $1 script set the engine in motion literally & thematically. McGinty (Brian Donvel) is a prototype of the well-meaning idealist, caught up in events that are either above his understanding or beyond his immediate interests. (Sturges returned to this base model of leading character in The Lady Eve, Sullivan’s Travels, The Palm Beach Story & loosely in Christmas in July). In this case, Sturges takes on the hypocrisy & lunacy of corrupt machine politics by placing the at first unwitting, then complicit & finally enlightened McGinty as the dupe of a city & statewide political machine. Only when he establishes a conscience, through the love of a good woman, is McGinty freed to be himself, unfortunately unleashing the downfall that Sturges frames the storytelling. By starting the picture in a bar, after the rise & fall of McGinty, Sturges alters the linear narrative in a pattern not unlike his earlier writing in The Power & the Glory (’33). In both cases he is able to subversively alter the telling of the story, by having a biased narrator re-create the past, perhaps romanticizing or embellishing elements. In typical Sturges fashion, however, the dupe is ultimately laid low and only marginally better off than at the start of wild tale. In The Great McGinty it is in the journey that the enjoyment comes as Sturges melds in the social messaging with the ridiculous & the sublime to lift McGinty to greatness. Leave it to Preston Sturges to run afoul with the Hays Office (Production Code enforcers) regarding his depiction of libidinous & sexually promiscuous soldiers in the midst of World War II, but that’s exactly what he did with The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (’44). The story of the aftermath of a drunken night between small town girl Trudy Kockenlocker (Betty Hutton) and a group of soldiers that leads to marriage, a pregnancy & significant legal charges, Miracle was delayed release for more than 1 year, in part due to its twisted subject matter, but also because of Paramount’s glut of quality product. At its core it wonderfully deals with the drunken & anonymous sex that is the basis for the mayhem that Sturges cooks up & William Demarest, as Trudy’s overly concerned policemen father, puts into high speed motion. Eddie Bracken, playing the hopelessly in love with Trudy fall guy, ends up on the run, fleeing form the overzealous cop & 19 criminal charges related to his alleged debaucheries of the night in question. Only the 11th hour inclusion of The Great McGinty’s governor McGinty (Donlevy) & political boss (Akim Tamiroff) saves the day for Trudy & the sextuplets she gives birth to. The Hays office of course objected to the casual approach towards promiscuity, but Sturges’ hyper-reality left them helpless to minimize or eliminate most of the surprising material. It’s as if it were all coming too fast, too furious & with too much conviction for anyone to determine what just happened, let alone what to eliminate. Dick Powell, who plays Jimmy, was a 1930’s song & dance man (Gold Diggers of 1933, 42nd Street & Footlight Parade) who stars in Christmas in July (’40) as an office boy/cum ad man duped not by the powers that be or an oppressive force, but by his co-workers, on a lark. That he is so gullible & so well meaning as to buy his girl a ring & his mother a bed with his ill-gotten winnings, aligns him with other Sturges heroes, but his grounded nature makes him somewhat unique. After the Maxford Coffee House cannot choose a slogan winner from a nationwide contest, Jimmy’s officemates forge a winning document that assures him $25,000. Sure Jimmy falls for it, but so does nearly everone else in his sphere, including his boss & most importantly Dr. Maxford (Raymond Walburn), who cuts him his winning check. The world is upside down, swirling around poor Jimmy as he commits to his girl, gets a surprising promotion at work and generally plays big man around the neighborhood. In a flip of the cynical nature of such a windfall, Sturges instead makes Jimmy better because of the windfall, instead of greedy & self-serving. In this way Sturges aligns the viewer with Jimmy & the joke is on everyone else. When he is forced to give up his ‘earnings,’ it is not to bring the mighty low, but to reinforce the unfairness of the ruse itself. Only Sturges’ ‘happy ending’ validates the meek over the mighty and the sane over the insane. Once again small town values come in conflict with a deliberate deception in Sturges’ Hail the Conquering Hero (’44), the last picture he made for Paramount. Woodrow Truesmith, in trying to live up to his dead father’s war hero status has told a white lie to save face for the cronic hay fever which has kept him out of WWII. Unfortunately, some well-meaning Marines, once again lead by the inimitable William Demarest, playing gunnery Mater Gunnery Sergeant Heffelfinger, build upon Woodrow’s falsehoods to cast him as a hero beyond reproach. When the towns people elevate him to a candidate for mayor it all becomes too much for poor Woodrow to bear. Sturges creates comedy from war more often than anyone, but it’s always with a sense of purpose. As John Sullivan realizes at the conclusion of Sullivan’s Travels, it is in the making of laughter that softens the everyday misery & sadness & perhaps that was Sturges’ greatest trip with his wartime comedies. Here, the ‘hero’ is not a hero until he is true to himself. He gets the girl, he gets the accolades, but it’s in the getting to the truth that so much of Sturges rests his whip smart comedy. While Sturges is often noted as one of the finest writer/directors in Hollywood history, he was at heart a writer, so including 2 pictures that he was credited with writing the screenplay seems necessary. The Power & the Glory (’33) stands out among this list because it is neither a comedy, nor something Sturges was particularly proud of as it appeared on screen. It has at its core a once good man corrupted by ambition, but there is no happy ending in the 3rd act; there is no redemption. Instead, there is a narrative structure that would be lifted 8 years later to tell a far more famous story of a man corrupted by ambition: Charles Foster Kane in Citizen Kane (’41). Just as Kane’s death triggers the retelling of his life, so too does Tom Garner’s (Spencer Tracy) death set in motion the story of his life and ultimately his regret. The framing of the story, with the conclusion as the starting point, was a unique construct in 1933, but it resulted in a less than successful box office performance. Garner is an illiterate railway worker who falls in love with a teacher who teaches his to read & write. With unbridled ambition & ruthless efficiency he rise to run the railroad, but at the expense of his marriage and his family. It is a surprisingly bleak story for Sturges, but one that Jesse Lasky (founder of Paramount Pictures) later noted “…was the most perfect script I’d ever seen.” (Curtis p. 83) Remember the Night (’40), on the other hand, was less of a perfect script by the time it was filmed, as director Michael Leisen made structure cuts that Sturges felt negatively affected his script. Sturges felt he had written a solid tearjerker; a story about a straight as an arrow district attorney (Fred MacMurray) & a world weary petty jewel thief (Barbara Stanwyck) whom he takes pity on. Their road trip home to Indiana, after he cynically gets a Christmas adjournment in her trial in order to get a less compassionate jury after New Year’s, is standard opposites attract romantic comedy, but with typical Sturges shananigans. About midway in the picture, however, Sturges interjects a scene of great poignancy & sadness when Stanwyck’s character returns to her mother’s home only to be insulted and thrown out. It’s a scene seemingly from another movie, but Sturges juxtaposes it with MacMurray’s character’s homecoming to make Stanwyck more sympathetic & begin her transformation to a Camille-like character possible of self-sacrifice. Finally, there is Unfaithfully Yours (’48), a wicked comedy that Sturges made for 20th Century Fox after leaving his home at Paramount, that really is about the mind of the creative genius and its potential towards madness. Perhaps a reflection of Sturges’ feelings towards his studio overlords, Unfaithfully Yours is the fever dream imagination of Sir Alfred deCarter (Rex Harrision) as he concocts 3 separate scenarios of killing his wife all while he conducts 3 separate pieces of classical music. Unfortunately, when he sets about to actually commit the crime his ineptness takes hold and he simply makes a mess of the murder scene, before any murder has taken place. The fact that his wife wasn’t even unfaithful is nearly lost before the finale. The brilliant use of the specific musical pieces to launch & reflect each of the 3 scenarios shows Sturges on top of his creative game, but the movie was not a box office success. After the previous 8 movies for Paramount it is no wonder because it can be viewed as either too smart or not funny enough to have the mass appeal & garner full critical praise (although it did receive generally positive reviews). In some ways Preston Sturges was too good for the movies. He worked at a time when the 6 major studios controlled production with an iron fist and routinely altered, reworked or destroyed a writer or directors creative endeavor. That he was allowed to write AND direct did give him an inordinate amount of creative control over his projects, but he was still subject to the same whims of studio bosses as other folks. That his 8 great pictures stand largely as he imagined them are certainly proof positive that his genius withstood or repelled meddling. He will always go down as a prime example of the autuerist theory of the director as the creator of the film because a Stuges film is above all else a “Sturges film” and can be easily identified. Enjoy the 8 films, but search out he others because there is always at least a germ of “the Sturges film” in everything he imagined.

0 Comments

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

- Anatomy of a Murder Notes

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed