|

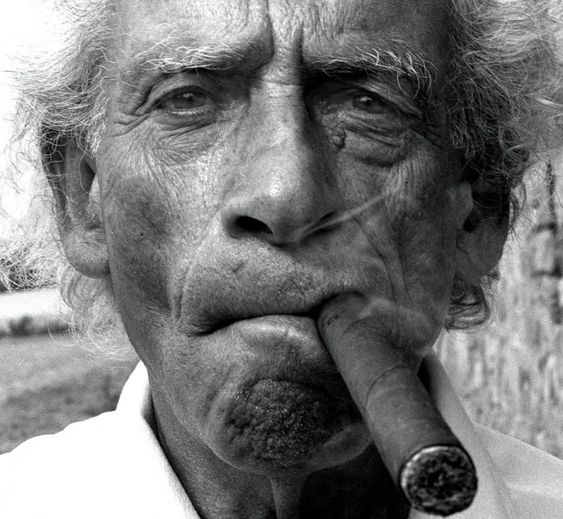

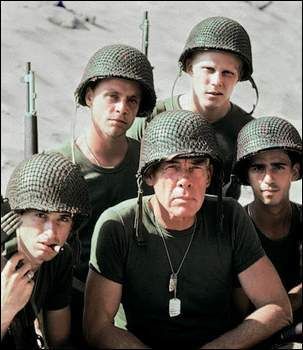

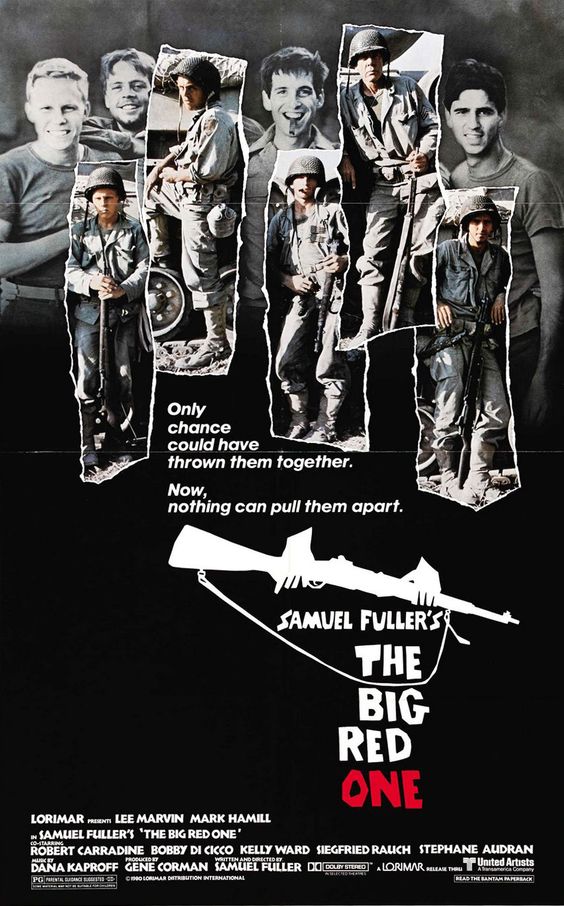

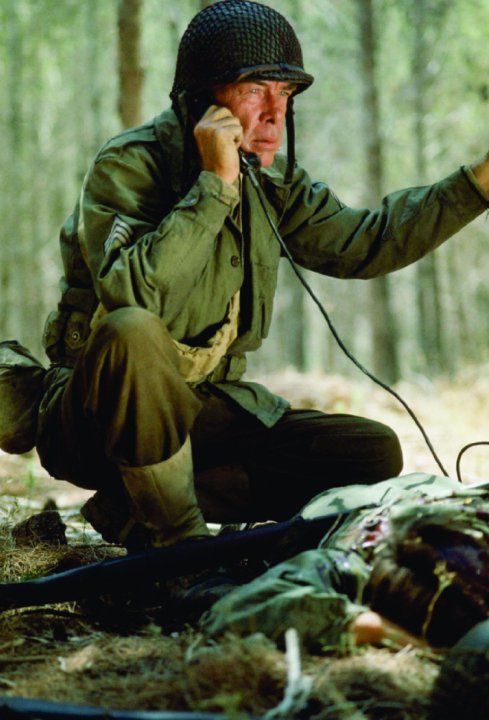

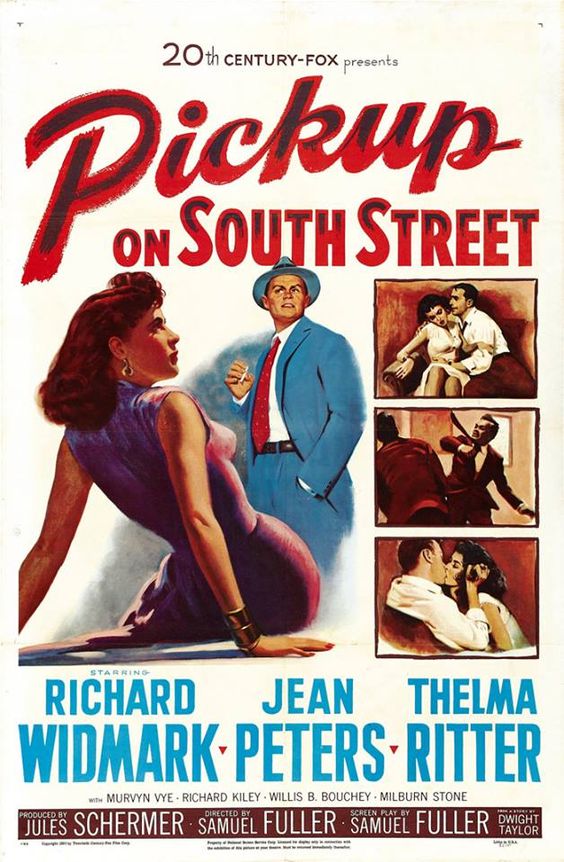

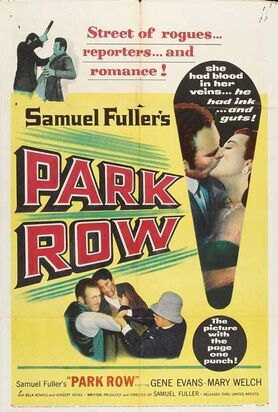

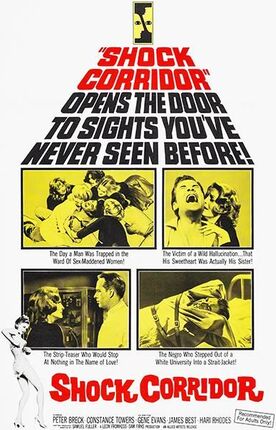

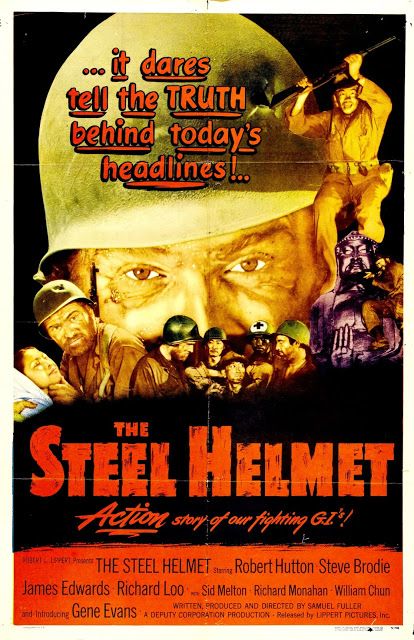

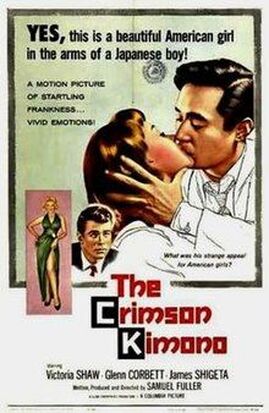

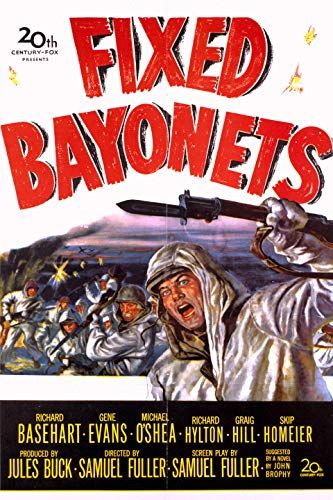

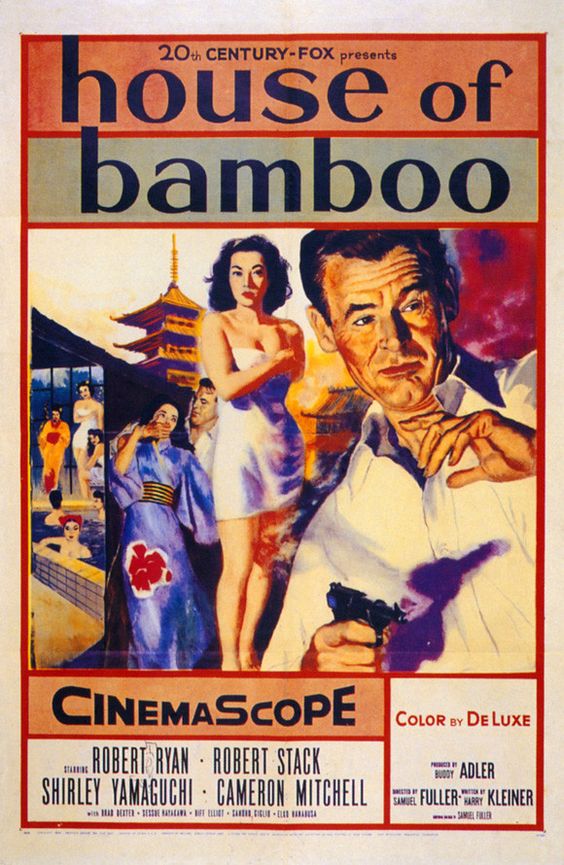

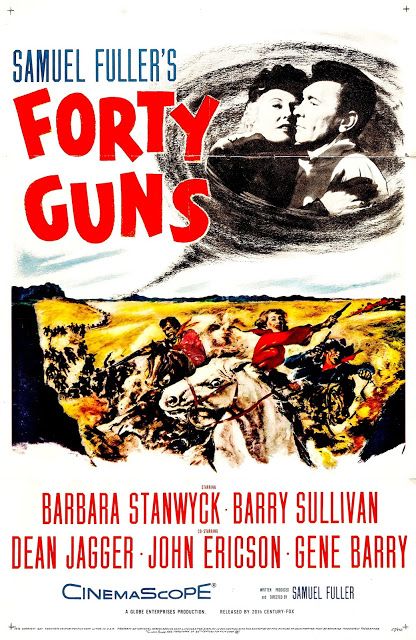

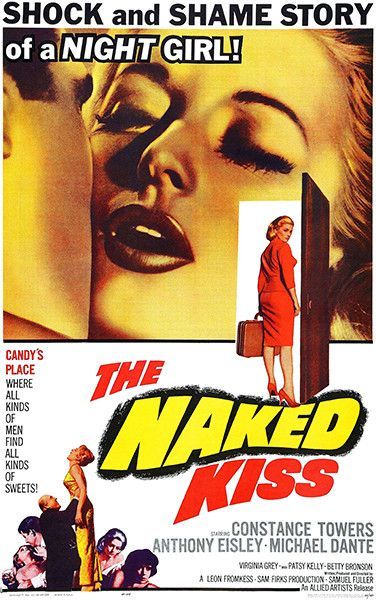

Sam Fuller lived 2 lives before he became a movie director at age 37. First, beginning when he was 12, he was a newspaper man, starting as a copy boy & rising to a crime reporter for a New York daily when he was just 16. For most of his life he considered himself a newspaper man at his core, but in his late 20’s he enlisted in the Army to serve during WWII. Turning down an offer of rear-guard safety as a military reporter, Fuller insisted upon being placed in the infantry on the front lines & served for 4 years with great distinction. Many of his greatest films reflect his time in The Big Red One, fighting in the First Infantry division, in North Africa, Sicily, on D-Day in France, in Belgium & finally in Czechoslovakia, where he helped liberate a Nazi death camp, recording what he saw on his 16mm camera. The combination of man’s inhumanity towards his fellow men, as he witnessed it on the streets of New York & in combat overseas, and his unflagging ability to tell stories, led him towards his unique style of filmmaking; a style that is violent, unforgiving & unsympathetic, yet filled with the very essence of humanity at its core. His films were rarely praised when they were originally released, but his body of work has found favor with filmmakers as diverse as Steven Spielberg, Jim Jarmusch, Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese & Francois Truffaut. His method was to rehearse a scene until it was perfected, then shoot it just once & he relied on fluid camera movement instead of cutting to achieve maximum emotion. Since he also wrote most of his films, the dialogue also reflected a minimalist hyperreality that could be jarring, like a single shot rifle, or spit out in rapid fire succession to heighten the intensity and emotional reaction. His sets were often as basic as he could make them, reflecting his limited budgets, but also his sensibility to focus on the actors & not the surroundings. Similarly, his lighting was generally from a single source & flat, lending an oppressive feeling in his interiors. Fuller himself defined his outlook on film when he said, “you have hate, action, violence, death…in one word, emotion.” Fuller’s Top 10 relies heavily on his wartime experience, but also reflects an ability to capture the core of many genres & styles. Most importantly, however, his films in their totality, capture, perhaps more so than any other filmmaker, the filmmaker’s beliefs, understandings & personality in its purest form. Fuller is his films & his films are Fuller. Sadly, Fuller wasn’t alive when his greatest work was finally unveiled to his audience & fans. The Big Red One was first released in 1980 in a condensed version that did not reflect Fuller’s fictional retelling of his time in combat. Cutting Fuller’s version from 4 & 1/2 hours to 1 hour & 53 minutes, producers eliminated important scenes, impactful characters & transitions that not only tied the film together, but would have given it an epic, yet intimate quality. Even in this truncated version, The Big Red One was nominated for the Palme d’Or at the 1980 Canne Film Festival & praised as one of the greatest war movies ever made. By the time 50 minutes had been restored to the film in 2004, to more closely resemble Fuller’s original vision, Fuller had been dead for 7 years. What was then released in 2004, while still not complete, is a masterpiece in emotional movie making. The story of a WWI veteran sergeant (Lee Marvin) & his ‘4 horsemen’ infantrymen as they make their way through the most important touchpoints of WWII has no emotional speeches & no super hero depictions of bravery, but instead portrays war for what it is, a cruel and ultimately random struggle for survival. The brotherhood between the five is never verbalized, but Fuller brilliantly illustrates their emotional bond through small gestures & a shorthand of shared experiences. Ultimately, the 5 characters appear to be each a part of Fuller himself & reflect the entire arc of his experience serving in World War II. Pickup on South Street ('53) is a classic Film Noir that naturally flows from Fuller’s experiences on the streets as a crime reporter. When he pitched the film to Darryl F. Zanuck, the head of 20th Century Fox, Fuller outlined the three main characters as a pickpocket, an informant & a floosie (to smart to be a kept woman & too dumb to be a prostitute). When Zanuck asked where the hero of the picture would be, Fuller responded that there was no hero, only people trying to scratch out their existence. Zanuck, in a rare example of magnanimity, agreed to let Fuller proceed, for which Fuller was eternally grateful. Fuller wanted as realistic story as possible & chose actors who could embody the characters as he saw them. Richard Widmark’s 2-time loser pickpocket Skip McCoy is a study in self preservation as a lifestyle, while Jean Peters’ Candy isn’t very bright, but she wears her heart on her sleeve. Thelma Ritter’s tie-selling police informant, however, is a piece of art all its own. It’s as if she channels Fuller’s gruff pragmatism with the quiet desperation of a life poorly lived to create one of the most indelible performances, certainly in Noir, but perhaps in the entirety of the 1950’s American movie. Ritter’s final scene is played & directed to perfection, with Fuller’s camera moving first towards her as she resigns herself to death, and then to the turntable as the song & her life ends. How different the film could have been with several actresses who wanted to play Candy: Shelly Winters, Ava Gardner & Betty Grable all approached Fuller, with Grable insisting on a dance number to seal the deal. Even Marilyn Monroe, a Fox contract player, read for the part, but Fuller insisted she was too beautiful. Creating a mis en sin at the lower rungs of criminality Fuller wanted neither movie stars nor glamourous settings, choosing instead to model the backlot sets on the Italian Neo-Realism of Roberto Rossellini (Rome, Open City –’45), Vittorio De Sica (Bicycle Thief-’48) & Luchino Visconti Bellissima-’51). What he created is a tender & ruthless depiction of people on the outskirts of society, struggling to hang on & he wrapped it in yarn with serious topical & political overtones. By having American spies trading secrets with identified communists Fuller opened himself & his film to scrutiny not just from the Production Code office, but also the FBI & J. Edgar Hoover himself. According to Fuller’s autobiography, Hoover demanded a meeting with he & Zanuck where Hoover opened the conversation by telling Fuller that he didn’t like The Steel Helmet or Fixed Bayonets, both made in 1951, but that Pickup on South Street had gone too far. He particularly took offense to the scene where Ritter is haggling with 2 FBI agents & a cop over how much she should be paid for information. Fuller relied on his years on the crime beat to note that he had personally witnessed the scene playout in real life. When Zanuck backed the director the meeting ended & the scene was not changed. Fuller’s life in the newspaper business plays out in quite a few of his films, but nowhere greater than in his love letter to late 19th Century journalism on the streets on Manhattan, Park Row (’52). Named after the famous street where most of the NY dailies had their offices, Park Row tells the story of Phineas Mitchell, played by Fuller favorite Gene Evans, & his righteous desire to run his own paper “the right way.” Fuller makes the story all about the fine balance between real journalism & the corporate mentality to sell more papers, no matter what the price. While the costumes date from the 1880’s, the story is as relevant today as it was when Fuller made it. Every scene is an opportunity for Fuller to draw the distinction between the grinders who looked at their profession as a calling & a service to their readers & the muckrakers who put profits & greed ahead of all else. Shock Corridor (’63) takes righteous journalism to it’s most extreme in showing a reporter’s willingness to risk everything to solve a murder in a mental hospital. In an effort to win a Pulitzer Prize, reporter Johnny Barrett (Peter Breck) gets himself committed to a mental hospital where one of the patients recently died. Fuller uses the words of the patients to both tell the story of the murder & spout harsh truths about society’s often ignored darkness. A black patient spouting white nationalistic rhetoric, a nuclear scientist reduced to a babbling 6-year old & war veteran reduced to believing himself a confederate general, each show how society’s norms can be re-written by changing the context of its representation. Yes, the patients are insane, but Fuller illustrates the fine line between sanity & insanity as Barrett pieces together the truth just as his own sanity begins to slip away. Shock Corridor had a long gestation period for Fuller, it had originally been prepared some 15 years earlier for Fritz Lang to direct, but when Lang wanted rewrites to allow for Joan Blondell to play the journalist, the deal fell apart. His original story intent was to show the deplorable conditions inside a mental hospital, but as the story evolved he chose to invoke the “theatre of the absurd” to have a greater impact on society as a whole. The characters are broadly drawn, but capture the exact emotional note that Fuller wanted to promote. 4 years earlier, with The Crimson Kimono (’59), Fuller bridged the gap between the racism that lingered from WWII & the Civil Rights movement that would dominate the ‘60’s. Two Korean war veterans, one white, Charlie Bancroft (Glenn Corbett) & one Japanese American, Joe Kojaku (James Shigeta), are partners in the police department out to solve the murder of a stripper in the Japanese quarter of LA. Charlie & Joe are like brothers, Joe’s blood having saved Charlie while the pair were in the war, but their relationship is tested when a white student artist, Christine Downes (Victoria Shaw), helps them solve the crime. Charlie initially has feelings for Christine, but when Joe takes an interest, and the interest is returned, Joe mistakes Charlie’s jealous reaction as pure & simple racism. Fuller’s twist, by showing the racism in the minority character, flipped the script on the root of hatred & the chance that mis-communication may exacerbate an already tenuous & superficial understanding of race relations. In setting up both characters as good regular guys who care about each other Fuller further deepens the emotion in his story. In fact, Columbia Studios production chief Sam Briskin asked Fuller to at least “make the white guy a son of a bitch” to set the audience to accept Christine choosing the Japanese American. Fuller’s response was typical of his feelings for oversight on his pictures. “No, I can’t! A girl can’t be a little pregnant. She is or she isn’t. My white cop is a regular guy” (Fuller, p. 375). As the entire story is based on perceptions versus reality, the murder plot has parallels with the partner’s understanding of each other & while the murder is neatly tied up, the cops’ relationship is more ambiguous. Fuller’s style of filmmaking, blunt, straightforward & without pretense of puffery, lent itself perfectly to the Film Noir genre. The aforementioned Pickup on South Street is an unquestioned classic, but Fuller toyed & manipulated typical Noir conventions well into the ‘50’s, moving beyond black & white cinematography & chiaroscuro lighting into saturated colors to created House of Bamboo (’55), a remake of Street with No Name (’48). Robert Ryan plays Sandy, the leader of a criminal group of former GI’s in post WWII occupied Tokyo. As in The Crimson Kimono, there is an interracial love story, but Fuller complicates the story by adding subtle elements of a homosexual longing in Sandy that manifests itself in his attitude towards Robert Stacks Eddie Kenner. Kenner, who is an army investigator planted in the gang, is in love with Mariko (Shirley Yamaguchi), the widow of a former gang member & swiftly becomes Sandy’s favorite. By placing the story in Tokyo, Fuller completely warps any elements it shares with Street with No Name, most notably giving the film a surreal feeling by contrasting the history & culture of the city with the brutality of the criminal element. That the criminals are foreigners places them outside the milieu, creating a layered effect of one thing on top of the other & not a part of it. The wonderful factory robbery scene & the finally in a roof top amusement park are both wonderful examples of Fuller’s talents at shot making. Nowhere in Fuller’s filmmaking is his personal code more evident than in his war movies. Nothing in his life had a greater impact on him than his time in the service & his ability to translate that experience into his films was at the heart of his genius. His treatment of everyday soldiers, worried about living another day, respecting, but not necessarily agreeing with superiors, is manifested in the platoons that form a family in both Steel Helmet (’51) & Fixed Bayonets (’51). Both set during the Korean war, the films focus on how a group of regular men come together to overcome long odds. That may not sound like a unique synopsis for a war film, let alone 2, but in Fuller’s hands both films become a series of small moments between comrades that add up to profound statements about love, sacrifice & honor. In Steel Helmet Fuller reflects the racial diversity that makes America, and by extension the American military great, while also confronting the racism that threatens that greatness. After the group of survivors come together, including a battle-hardened sergeant, a black medic, & an Asian American GI, their unity is threatened by a captured North Korean officer’s harping on the racism the minorities face in the U.S. Once the outfit escapes imminent death, however, the sergeant responds when asked what unit the group comes from by simply replying “US infantry,” verbalizing the unity that bonds the men together. Fuller, always the economizer when working for independent producers, made Steel Helmet in 10 days for less than $150,000. Preferring unknown Gene Evens, a favorite of Fuller’s, to play the crusty sergeant afforded Fuller a lower budget, even though he had been approached to have John Wayne star, noting “that would have taken all the reality out of the film…With Wayne I would have ended up with a simplistic morality tale” (Fuller, p. 256). Instead, Fuller ended up with a somewhat incendiary movie that conservative reviewers called “pro-communist” & “anti-American” & which raised the hackles of the Pentagon so much so that they called Fuller to Washington to answer questions about the film. The furor did not but increase box office revenue & Fuller ended up pocketing a couple of million dollars, all the while happily thumbing his nose at those who questioned his patriotism. Fixed Bayonets ('51), released just 10 months later, proved once again that Fuller was most at home reflecting the lives of everyday soldiers fighting against long odds. A platoon is left behind to protect a narrow mountain pass, while covering the retreat of an entire division. The platoon is comprised of a cross section of soldiers, but instead of racial identities, Fuller focusses on what it means to be a leader & what it means to be a good soldier in the face of imminent death. Evans stars yet again as a battle-hardened sergeant tasked with leading the men after the initial leader is killed. As the deaths mount, different men are tasked with leading the platoon, some more skilled & some more reluctant, but Fuller wonderfully shows that not only are their different styles of leadership, but there is different types of heroism. Fixed Bayonets stands out as a film produced by the Hollywood system (produced by Darryl Zanuck for 20th Century Fox), yet willing to show that battles are not all heroism & glory, but a nuanced mixture of bravery, stupidity, cowardice & genius. Because it was made for Fox, however, Fuller was able to double his shooting time to an incredible 20 days & the film had a premiere on each coast. Forty Guns (’57) was the last of the pictures in Fuller’s very fruitful partnership with Fox & further shows his mastery of film language. Taking, what at the time was a long in the tooth genre, the western & breathing fresh life into it was no small feat. What john Ford had done the year prior in The Searchers (’56), turning normal western conventions on their ear by making the hero a despicable man hell bent on revenge, Fuller furthered by making the anti-hero/villain of Forty Guns a woman, complete with back attire & a harem of available men. The introduction scene of Barbara Stanwyck’s Jessica Drummond, when she & her 40 men ride in formation & encircle the Bonell brothers, is as arresting & inventive as it is intimidating. It has the equivalence of a cavalry charge, but the ominous feel of a native attack. It’s Fuller at his best, utilizing everything at his disposal, including Fox’s proprietary CinemaScope wide lenses, which only add to the immensity of the scene. Stanwyck’s performance is also intense & mean & fierce, allowing Fuller, for the first time, to have a female character lead his film. Leave it to Fuller, however, to have it’s lead male character question the very nature of the code of the west by swearing off his past role as a marshal by calling the job nothing but “legal killing.” In one of the greatest climactic gun battles, Griff Bonell (Barry Sullivan) is forced to choose between killing the town bully, while he holds his lady love, or lay down his weapon & letting his escape. Fuller, always the master storyteller, provides a wonderful twist that has been used countless times since! Finally, there is The Naked Kiss (’64), Fuller’s most audacious & daring film. The opening scene alone, where a prostitute fights for her life, exposing her bald head, then throwing a wad of cash at the immobile attacker. It’s arresting to say the least, & puts the viewer immediately off kilter, but it does nothing to prepare the viewer for what will come later; what will never be spoken, but will be evidently clear as the plot unfolds. It’s Blue Velvet (1986, David Lynch) 22 years earlier, in that it paints a superficial normalcy over a decaying & morally bankrupt undercurrent. As in most of his films, Fuller takes risks that offer great rewards & The Naked Kiss is Fuller’s masterwork of subversion & perversion. I watched Naked Kiss for the first time about 15 years ago, but before I had knowingly watched much Fuller & I wasn't prepared for it. It's direct & in your face the entire time & it's really only after a couple of times watching it that i can truly appreciate what Fuller was trying to do.

If everyone lived the life that Samuel Fuller lived the world would be a much more interesting place. Instead, we are left with his cinematic legacy & it’s reflection on that life. It is a yarn well told.

3 Comments

|

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

- Anatomy of a Murder Notes

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed