|

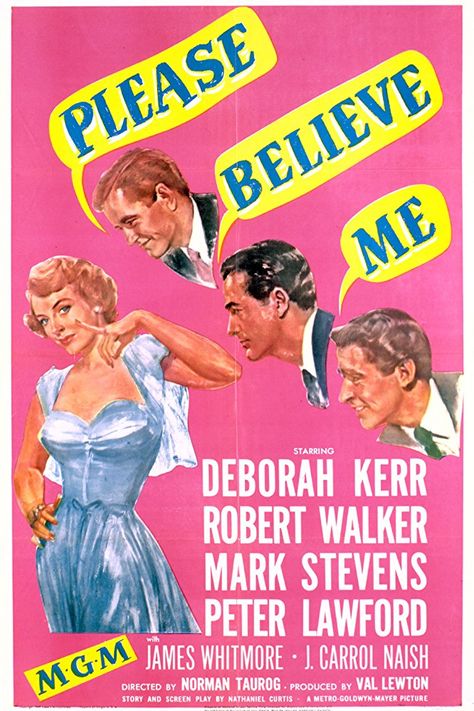

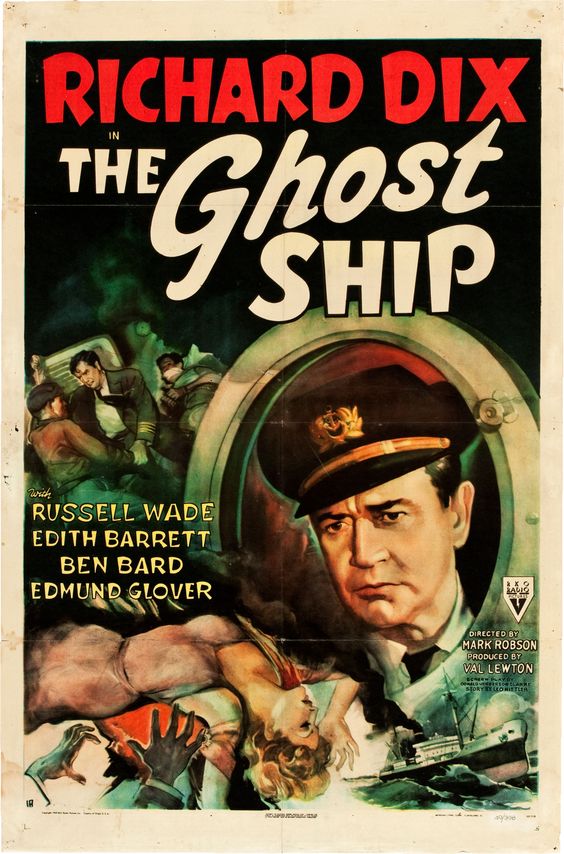

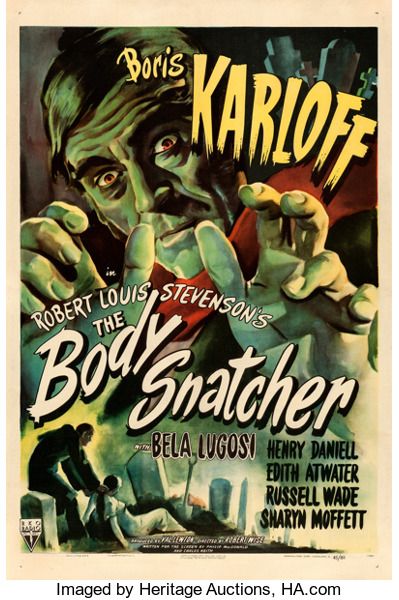

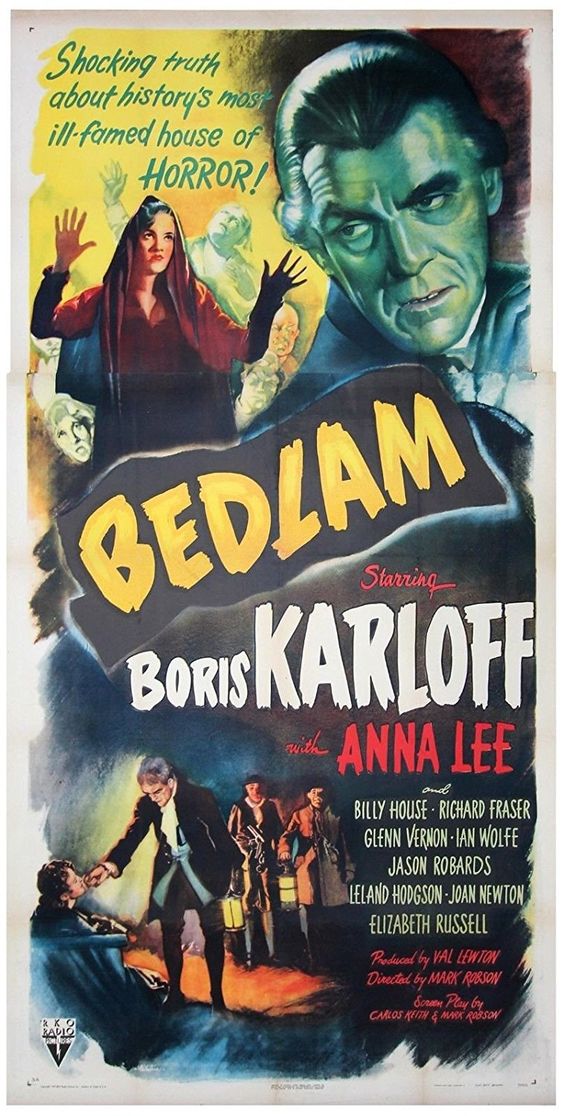

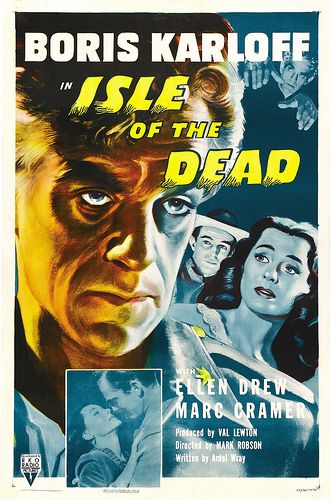

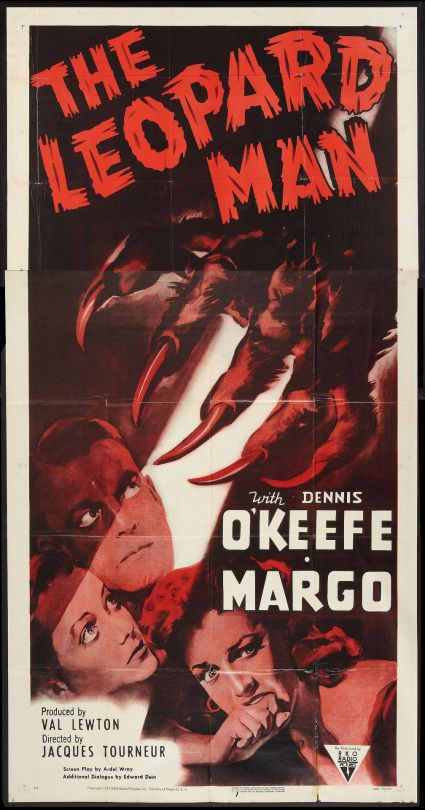

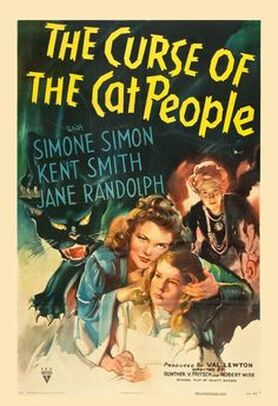

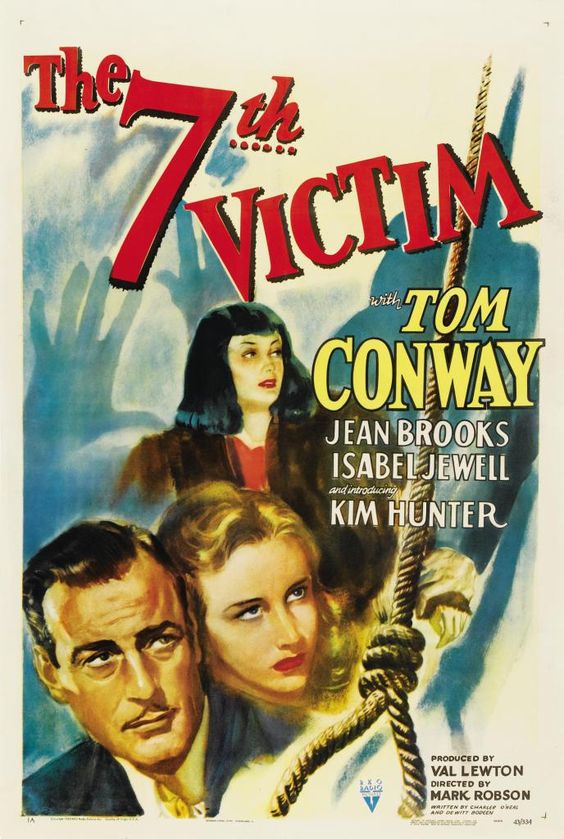

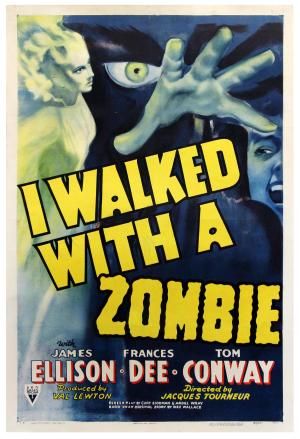

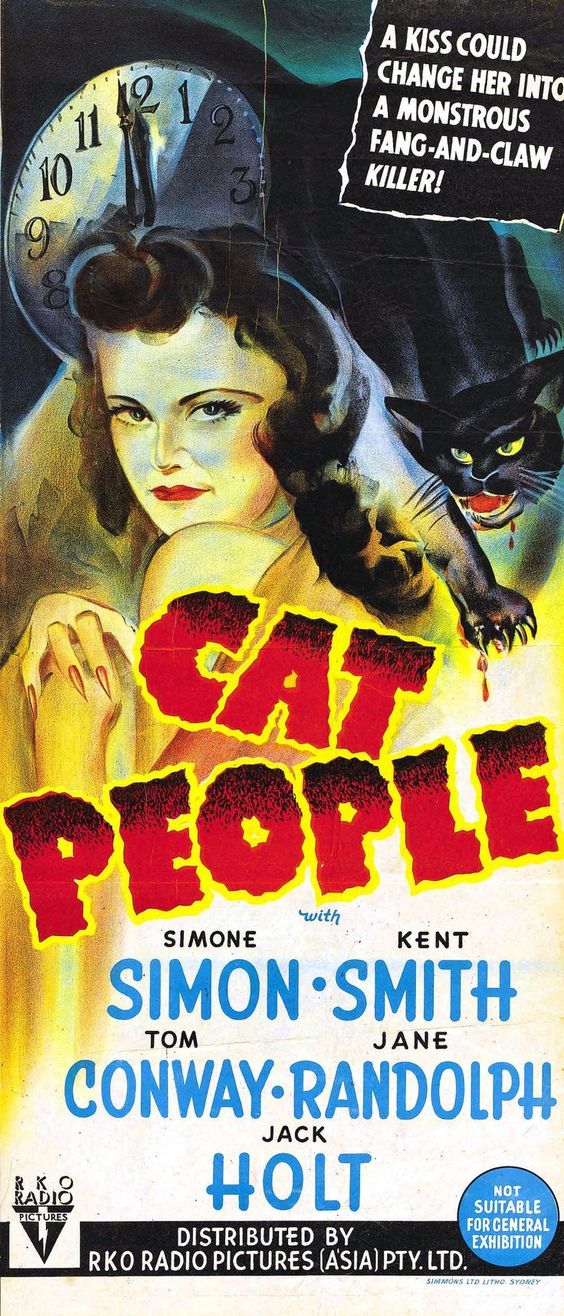

The Rationale: In Hollywood history there are a handful of producers who are well known to even casual fans; David O. Selznick (Gone with the Wind, Rebecca), Irving Thalberg (MGM), Samuel Goldwyn (The Best Years of Our Lives) & Darryl F. Zanuck (All About Eve, The Grapes of Wrath) were all feted with accolades, fame & Oscars. On the flip side of Hollywood, however, were a bevy of unknown producers who churned out quality content, some on shoe string budgets for smaller studios. One such producer, and perhaps the best of the rest, was Horror producer Val Lewton, who created a collection of classics for mini-major studio RKO during the middle 1940’s. Lewton had come to RKO from David O. Selznick Productions where he was a story editor & general boy Friday, having never produced a film himself. Because he studied at Selznick’s feet however, (Lewton wrote the scene in Gone with the Wind that ends part 1 at the train station where the Confederate Army lay dying), he was more than prepared for creating a new unit. In fact, RKO president Charles Koerner had hired him based on a misunderstanding, after hearing someone describe Lewton as “…a writer of horror novels”, when the person speaking actually said he was a person “who wrote horrible novels.” Koerner, at the time interested in creating cheap knockoffs of the Universal monster pictures, jumped at the chance to bring in a “horror” writer who worked for Selznick. Given shoe string budgets & ridiculous titles, like Cat People (’42), I Walked with a Zombie (’43) & Leopard Man (’43), Lewton redefined the horror genre that had been run over by the creature features of the 1930’s (Frankenstein ‘31, Dracula ‘31) & ‘40’s (The Wolf Man ’41). The 9 psychological horror films that he produced in a span of 4 years represent the best of auteurist Hollywood, where 1 man, with the assistance of a talented team, could craft true art out of scraps of ideas. Because of obvious budget constraints ($150,000 per picture), Lewton had to make due without being able to invest in either monsters or lavish sets. Starting instead with the script for each picture, Lewton & his writers took the germ of the title, infused it with the fear of the unknown, then photographed each film in very stark blacks & whites, hiding would should not be seen to enhance the fear factor. Focusing on elements of superstition, voodoo, ancient curses or insanity, Lewton’s scripts (he never took credit, but worked with writers like DeWitt Bodeen, Curt Siodmak, Ardel Wray, & others) took the form of ghost stories set in the modern world. His protagonists had jobs, they lived in normal cities & had normal lives, but there was always nighttime & darkness to hide their basest fears. A shadow, a sound or an idea would take on mythic qualities, bringing out fear in the characters & terror in the audience. #10. Please Believe Me (1950). Lewton produced 5 non-horror films, but only 2 during his time at RKO. After his success with his B picture unit, however, he produced briefly at MGM & was given an A picture with stars Deborah Kerr, Robert Walker & Peter Lawford. Unfortunately, as with his 2 other post-RKO films, the results were not very good. Perhaps it was his health, as Lewton had experience heart trouble for some time & ended up passing away at age 46 just 1 year after Please Believe Me was released. Please Believe Me is the story of a recent heiress (Kerr), who is wooed by a scam artist (Walker), a millionaire playboy (Lawford) & his lawyer (Mark Stevens). Kerr is her usual adorable self, but the plot is redundant & the conclusion fairly predictable. It’s fine mindless entertainment, but does not measure up to the early work of Lewton. #9. The Ghost Ship (1943). The Ghost Ship is a curious film because it was virtually lost for several decades, the result of a plagiarism suit against Lewton & RKO. Fearing more recriminations or lawsuits RKO shelved the film shortly after its initial release. The ominous opening of the film, of a blind beggar warning a new 3rd mate (Russell Wade) against boarding the ship, is reinforced once on board by a mute sailor stoically sharpening his knife. What ensues is a straightforward mystery for the 3rd mate to convince his shipmates that there’s a murderer on board. Like all of Lewton’s films, he was given a title, but in this case, he was also tasked with creating the film around an actor, Richard Dix, who owed RKO one more film on his contract. Dix had been a major box office draw in the ‘30’s & received an Oscar nomination in 1931 for Cimarron, but he would retire from film 4 years after The Ghost Ship. It’s a well made film that deals with authority, order & respect, but because it lacks the pure psychological undertones of his other films, I’ve had to rank it last among his RKO 9. #8. The Body Snatcher (1945). The Body Snatcher is the 2nd of three films Lewton made with horror luminary Boris Karloff (Frankenstein ’31, The Black Cat ’34). RKO brass had thought it wise to bring the legend to the studio as a way of giving credibility to its horror unit, an idea Lewton initially deplored. Fortunately, the 2 men forged a lasting friendship based on mutual respect, a joy in classic literature & a similar temperament. Proving that Karloff was a skilled actor, Lewton reshaped his personae, giving him a crass & manipulative role, just as sinister as some of his earlier films, but with more depth & dimension. Karloff plays grave robber John Gray, who manipulates and murders freely, all while collecting bodies for medical research. His scene with Bela Lugosi is a many layered delight, as the 2 legends play villain & victim to a tee. The malevolent evil presence of Karloff centers the film & creates the physical manifestation of doom that Lewton utilized in many of his later films. The production of the film is also a testament to frugality as Lewton created Edinburgh of 1831 on RKO backlots with wonderful attention to detail & within his meager budgetary constraints. Similar to The Ghost Ship in its straightforward telling of the story, The Body Snatcher lacks the poetry of some of the earlier films higher on this list. It’s definitely worth watching for Karloff’s performance, but it’s also well made & an entertaining story. #7. Bedlam (1946). If The Body Snatcher sets Karloff as the twisted center of a murder story, then his performance in Bedlam is the shadow that darkens every corner & intimidates every pathetic creature under his ‘care.’ Karloff plays Master Sims, the despotic & miserly overseer of a mental asylum in 1761 London, out to court the bourgeoisie into supporting his asylum. Anna Lee, who later played on General Hospital for 24 years, co-stars as Nell Bowen, a kept ‘actress’ who tries to influence the ridiculously stupid Lord Mortimer (Billy House) into enacting reforms at the hospital. Sims manipulates the system to have Bowen committed & the film really starts to get good. Lewton & director Mark Robson first paint the inmates through the eyes of the upper class, but once Bowen is committed there is a sensitivity to mental illness generally unseen in other films of the era, with many inmates given dimension. In doing so, the story shifts what is considered scary from what is inside the hospital to what is outside & that is the brilliance of the film. There are wonderful moments of tenderness & the death that climaxes the film is as chilling as I can remember from a film in the ‘40’s. Cinematographer Nicholas Musaraca, who shot most of Lewton’s films, fills the frame with cut lines, dark spaces & textured surfaces, adding a Noir element to this and so many of Lewton’s other films. Sadly, this was Lewton’s last film at RKO, but certainly enforced the talent that he and his team possessed in create real fear & terror. #6. Isle of the Dead (1945). The first & the best of the Karloff films focuses on a group quarantined on an island after one of them is exposed to the plague. Chief among them is Karloff, a Greek general, who has left the battlefield across the bay to see his wife’s grave. A motley crew consisting of an American reporter (Marc Cramer), A British consul & his wife (Alan Napier & Katherine Emery), their charge (Ellen Drew), & others, including an old peasant woman who believes the rolling death isn’t the fault of a plague, but rather evil demons called vorvolakas, culled from Greek superstition that drain the life of the weak, while giving themselves vitality. While this film is not often listed among Lewton’s best, I enjoyed its blend of the superstition of his earlier work with an ever-shrinking circle of characters, as death takes hold. The death of the consul’s wife is particularly terror inducing. It’s an uneven film to be sure, but the slower parts offering exposition still offer Karloff in an interesting performance. #5. The Leopard Man (1943). In some respects, Lewton’s RKO films come in batches of 3. There are the 3 Karloff films, but most importantly there are the 3 films directed by Jacques Tourneur, the last of which is The Leopard Man. The infinite wisdom of RKO executives separated the 2 geniuses after this film, assuming they could get twice as much quality by putting them each on their own film. While Tourneur did go on to have a fine career, and directed the Film Noir classic Out of the Past (1946), his films with Lewton stand out for their technical brilliance & incredibly efficient storytelling. The Leopard Man does indeed feature a leopard that has escaped from a nightclub act & is suspected of murdering several young girls. One of the interesting elements of the film is its shifting point of view, which is unusual for a thriller & creates an unbalance that adds to the mystery. The viewer moves from character to character, never sure where to fully invest, which adds depth to the straightforward mystery story. In typical Lewton fashion, most of the violence takes place off screen, but in one of the most terrifying sequences in Lewton’s canon, a young girl is stalked by the leopard on her way home from the grocery store, in a clear riff from Cat People, but with a far more devastating conclusion. This is the film that’s not for the faint of heart, for each of the 3 murders is chilling in its own way & more personal because of the shifting point of view. #4. Curse of the Cat People (1944). While this may not be my favorite film, I think it perfectly paints what Val Lewton was all about in creating the B movie horror unit at RKO. After the success of Cat People (we’ll get to that later), RKO wanted to cash in with a sequel. What Lewton crafted, instead, was his most personal film that had as little to do with the original as any sequel I can think of. He was smart enough to cast all three of the main stars from Cat People (Simone Simon, Kent Smith & Jane Randolph), but he & writer DeWitt Bodeen essentially moved them to secondary characters to focus on Oliver & Jane’s child, marvelously played by 8 year-old Ann Carter. Casting back to his childhood, Lewton added bits of specific memories (the magic tree mailbox, the specific method of learning numbers), but more importantly gave Amy the inventive imagination initially disparaged by the adult world that Lewton dealt with growing up. Friendless & the focus of her father’s frustrations, Amy invents an imaginary friend after finding a picture of Irena (Simon), her father’s first wife from Cat People. Oliver immediately verbalizes his concerns that Irena has somehow infected his daughter’s imagination, just as Jane explains the presence of Irena’s painting in the Reed’s living room, “it’s as if this house is cursed by Irena, but Oliver insists on the painting remaining.” A friendly old neighbor & her murder intentioned daughter add a bit of danger to the affair, but it’s really Oliver’s coming to grips with the events of Cat People, rather than an extension of that story, that drives the narrative, albeit seen through a child’s eyes & imagination. As one can imagine RKO was not pleased by this radical departure from the original & meddled throughout the production. Lewton, ever fearful of having the film taken away, fired the original director, Gunther Von Fritsch (noted for his documentary work), when he fell behind in shooting & replaced him with neophyte director Robert Wise, who would go on to win 2 Best Director Oscars for West Side Story & The Sound of Music in a 50 year career. The scenes captured in the Reed’s yard between Irena & Amy are magical, as Simon/Irena appears as both an earthbound angel & a fairy princess. (As evidence of RKO’s meddling, they removed a sequence where Amy’s idealized image of Irena as taken from a princess book, is explained. Because it was dropped from the film reviewers focused on Irena’s low-cut dress as a salacious distraction, instead of the imaginary princess of Amy’s dreams). Fortunately, the 3 relationships that Amy/Lewton has with Irena, the old neighbor & her father create a brilliant balance that makes this film not so much a horror film sequel, but a wonderful study of a child’s fears & apprehensions of an adult world. #3. The Seventh Victim (1943). If The Curse of the Cat People revealed much about Lewton’s childhood fears & phobias, then The Seventh Victim may reflect him as an adult. Containing as it does images of hanging, suicide & devil worship, Lewton, alongside writers Charles O’Neal & DeWitt Bodeen, craft a story around John Donne’s epigraph “I run to Death & Death meets me as fast, and all my Pleasures are like yesterday.” By allowing a character to argue that death may be better than life, Lewton sets in motion an eery reflection that illustrates his fears of rejection & failure that drove his professional work ethic. The film opens with Mary (Kim Hunter) leaving boarding school to search for her missing older sister. What she finds is an ever-increasing mystery around her sister’s whereabouts. The new owner of her sister’s company, her lawyer & a private detective make matters worse and point to foul play, but when she is brought in contact to a cult, things get really strange. What elevates The Seventh Victim is the moody atmospherics, punctuated by cage like enclosures that surround Mary, an ever-shifting avenue of darkness in both character & setting & finally, with the appearance of the sister, a sinister underpinning to everything. As in Cat People, The Leopard Man & other Lewton films, the central set piece is the sister’s (Jean Brooks) long walk through the dark streets of New York stalked by a knife wielding killer, complete with a starling jolt of surprise (“The Lewton Bus”). While the overriding theme of death versus life runs through The Seventh Victim its greatness lies in the pervasive sense of doom & the Noir-like photography & settings. I mentioned the cage-like rooms, but even the studio bound exteriors create oppressive visuals that add to the foreboding. #2. I Walked with a Zombie (1943). I Walked with a Zombie takes everything that was ridiculous about the titles assigned to Lewton & spins it into a dreamlike film that stays with the viewer long after a first viewing. The story of a nurse who journeys to the Caribbean island of San Sabastian to care for the invalid wife of a plantation owner, I Walked with a Zombie combines voodoo, Christianity, adultery and the history of the slave trade to weave a hypnotic retelling of Jane Eyre. Critic James Agee, a longtime champion of Lewton’s films, noted that Lewton skills were “poetic & cinematic, not literary or romantic” (Siegel, p. 100) & Zombie is the epitome of that sentiment. As noted, the film creates a dreamlike state, where interconnected moments are strung together in vignettes, instead of in typical linear fashion; nurse Betsy’s (Frances Dee) nighttime search for the wailing she hears, Betsy & the invalid Christine’s (Jessica Holland) walk through the cane field & the voodoo ceremony itself, are all shot without dialogue. This forces the viewer to search the screen for danger & for meaning, replacing dialogue to enhance narrative flow & reducing the movie to what Hitchcock would call “pure cinema.” It’s a stunning achievement that is further enhanced by the layering of a twisted love quadrangle between 2 brothers, one married to the invalid (Tom Conway) & the other her lover before her incapacitation (James Ellison), the catatonic wife & the newly arrived nurse, who attracts the affections of the husband. In the second film Tourneur directed for Lewton he achieves the highest level of direction by letting the images, brilliantly captured by J. Ropy Hunt, to speak for themselves & letting ideas, like the impact of the slave ship’s figurehead sit unspoken for the viewer and the island’s displaced former slaves. The revelation of the mystery behind the voodoo & the impact that it had on the family, headed by a missionary mother leads directly to the tragic conclusion. I Walked with a Zombie really is poetry in cinematic motion. #1. Cat People (1942). The first film in the RKO 9 made everything after it possible by being a box office smash & the highest grossing film for RKO in 1942. Because profit always supersedes artistry in the minds of Hollywood executives, Cat People’s success gave Lewton license to create everything else on this list. That it also stands the test of time as a psychological thriller of the highest order puts it at the top of my list. Irena (Simone Simon), is a newly arrived immigrant from Serbia who meets ship designer Oliver (Kent Smith) at the zoo while she sketches the black panther in its cage. She invites Oliver to her home where she tells him the story of a curse that has ruled her village for centuries where black magic turned people into cats. Regardless, Oliver falls in love with her & they marry, but she is weary of physical intimacy because she believes it will unleash the killer cat within her. From this psychosexual baseline comes a concise and mysterious ‘is she or isn’t she’ back and forth as Irena’s sexual fear causes jealousy and passion that she cannot control. A trip to a psychiatrist does little to help Irena & when Oliver falls in love with co-worker Alice (Jane Rudolph), Irena becomes unhinged, leading to one of the most terrifying sequences in classic Hollywood movies. As Alice takes a dip in a gym pool she is stalked by an unseen creature snarling as the light dances on the ceiling. The feeling of enclosure & terror is overwhelming & the conclusion does little to lessen that feeling. It’s a scene that has been often mimicked in horror movies & remains the benchmark for pure fright. While I Walked with a Zombie tells its story more elliptically, Cat People is very linear & straightforward a story, which only draws the viewer into the suspense and the mystery. A mysterious cat-like woman appears at Oliver & Irena’s wedding, calls Irena sister, then disappears into the night, punctuating a series of cat references that permeate the entire film & include statues, artwork, wall dividers, a pin & a live kitten (that clearly doesn’t like Irena). Signatures of Lewton’s future work would also be established in Cat People, most notably “the walk” & ‘the Lewton bus”, both of which make a heart stopping appearance during a late night journey through Central Park by Alice. Cat People is an original in a sea of second class B movies that were produced in the early 40’s and signaled the dawn of a genre changing run that would last until 1946.

Val Lewton was a complicated man. He was a man of letters who wrote pulp fiction. He was a procrastinator who led a profitable & dynamic team to make 11 films in 5 years. He was meticulous in his work, but generous with his time. And was extremely loyal in a town of sharks. Val Lewton didn’t set out to rewrite the rules of the horror genre. He never thought he or his films would be remembered. He was more interested in remaining employed and he was very intent on making the best films he could given the constraints placed upon him. He was an artist of the highest degree and his films not only stand the test of time, but carry the weight of all those that have used them to elevate horror & thrillers in particular, as well as film as a whole.

0 Comments

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

- Anatomy of a Murder Notes

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed