|

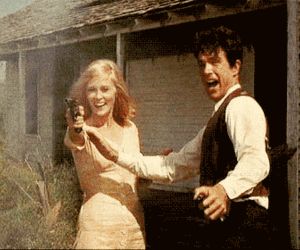

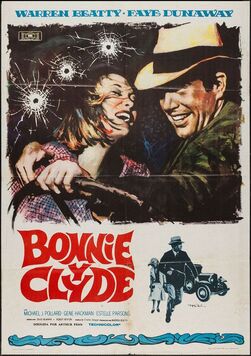

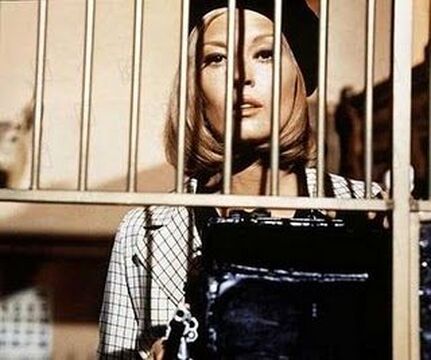

Arthur Penn’s brilliant biopic of Clyde Barrow & Bonnie Parker arrived on screen at an oft pointed to turning point in American film. The Production Code had been slowly crumbling for nearly a decade and the facade of the studio system was in complete ruin. In 1967, when the film was released, the Hollywood moguls who had ruled the industry with an iron fist for nearly 50 years had either died or been deposed and the quality of pictures were tired, bloated and largely uninteresting to the moving going public. The tentpole films were also ridiculously expensive, causing several studios to teeter on bankruptcy or look to outside investors to remain solvent. Into the breech came a younger breed of filmmaker, tutored on the films of the French New Wave, earlier Italian neo-realism and the recent British kitchen sink dramas. The dawn of New Hollywood was on the horizon and all it needed was a few well-placed films to bust the doors wide open. Mark Harris, in his wonderful book, Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of New Hollywood points to the 5 five films nominated for Best Picture Oscars for 1967, Dr. Doolittle, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, In the Heat of the Night, The Graduate and Bonnie & Clyde as either signaling the death nell (the 1st 3) or launching the revolution (the last 2). Doolittle was a bloated relic, while Heat of the Night & Coming to Dinner were middle of the road fables with a simplified message about race. The Graduate dealt with a modern story of disillusionment in upper middle class Southern California, but Bonnie & Clyde took a little-known piece of Americana to make a statement about love, poverty, desperation, sex and violence that would prove not only timeless and timely, but also the foundation that New Hollywood would build upon for the better part of a generation. Most Hollywood biopics, even those dating back to the silent era, fudged facts, misrepresented reality and sometimes even altered time and space, all to make a point through the story of real people, whether living or dead. Bonnie & Clyde is no different, either ignoring facts, like Bonnie’s real-life marriage at 16, or condensing them in a quick rat-a-tat-tat regurgitation, as Clyde does regarding his chopped off toes in his first meeting with Bonnie. By moving beyond elements that ultimately aren’t germane to the story or sharing well-known facts off-handedly, the filmmakers naturally condense the story to the filmic format. It’s manipulative to be sure, but it’s a timeworn part of the Hollywood biopic. Because Bonnie & Clyde was born out of a brief mention in a book about the short term rise of famous criminals in the early ‘30’s called The Dillinger Days (John Toland) and spurred the interest of credited screenwriters David Newman & Robert Benton should lead to expansion, not condensation of their story, but such is Hollywood. By focusing on the short, yet violent partnership, with little preamble or background, the film captures the essence of the pair without wasting time in exposition. Director Arthur Penn pointed to the first scene in the film as his favorite. It’s a simple mixture of close ups of Bonnie and longer shots of Clyde down below that immediately captures the essence of who the characters are, what their current state of mind is and the lightning bolt that rushes between them as their eyes first meet. As Bonnie mindlessly looks at first her lips, and then her eyes in a mirror, the closeups are jarring and in between those glances she moves around the room, clearly naked, as if waiting for something, a caged animal prowling. The diffused nature of the shots and the extreme close-ups are jarring in their immediate intimacy. The viewer senses her pent-up sexuality, her boredom in her current circumstance and her desire to escape; wonderful character development without distraction. Similarly, once she moves to the window the first shot of Clyde is Bonnie looking down at him, small and nervous, a kid caught with his hand in the cookie jar. When the camera switches to Clyde’s point of view, looking up at Bonnie, naked, protected by the window, but framed by it as well, his unease shifts to curiosity. She has put herself on display for Clyde and his immediate discomfort is transformed, almost cocksure, but unsure of himself and his circumstances. Bonnie sees him as her ticket out, but in the whirlwind he’s not so sure, looking hesitatingly after her as she scurries into a dress. Once she comes down, however, his demeanor changes to one of a smooth-talking playboy, first asking to come in, then offering to buy her a Coke-a-Cola. Clyde is a sexual contradiction from the get go. Beautiful to look at, confident enough to talk a good game, but inside he’s not so sure & uses braggadocio as a means of self-defense, which immediately leads to their first robbery together. Within the space of 5 minutes & 2 scenes, the characters reveal their needs, their desires and their mutual fascination with risk taking. While all this is going on, a striking visual motif foreshadows a key element in Bonnie and Clyde’s relationship; the use of visual props to substitute for phallic symbols. Clyde nervously flicks a matchstick up and down between his teeth, while Bonnie lovingly surrounds the opening of a Coke bottle with her lips in their opening scene together. The obvious implication is that both characters are sexually charged, but the story clearly moves in another way altogether. What’s interesting about this early foreshadowing is that what ended up in the picture is not only historically inaccurate, but doesn’t even come close to what the original screenwriters intended. Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker were passionately and physically in love and by all accounts had no problem expressing that love in the bedroom. Clyde was not impotent as plays out in the film. He was also not bisexual, as the screenplay reflected until just before shooting started. As written, Clyde, Bonnie and a fellow Barrow Brothers gang member, who morphed into the C.W. Moss character, have a threesome, with the implication being that Clyde preferred men, but Bonnie was an exception, such was their love. Newman & Benton worked under the assumption that Bonnie & Clyde’s relationship should not function as the backdrop to the story, but had to have a complication that vaulted it to the forefront. Because Beatty came aboard the project after reading only 25 pages, Benton cautioned him to get to page 47, where the menage a tois occurs before fully committing. Beatty read on and consented to Clyde’s orientation. Many rewrites, a change in ownership and noted screenwriter Robert Towne (Chinatown), all left the material in the screenplay. It wasn’t until director Penn made an impassioned and reasoned plea to the screenwriters that they agreed to remove the bisexuality and replace it with impotence. Penn’s argument was that if Bonnie & Clyde’s relationship was deemed deviant, a straight audience would identify them as freaks, refuse to identify with them and dismiss the story. The sexual energy remained, but was largely unrequited, a point made quickly after their first holdup, when in the throws of sexual excitement Bonnie presses herself into Clyde, only to have him recoil and note “I’m no lover boy.” If sexual frustration was the baseline conflict in the movie, then abject poverty and the effects of the Depression color the public actions of the duo. At one point Clyde expresses his surprise when a butcher comes after him with a knife, in an effort to thwart a robbery. “Clyde’s disbelief in expressing, I ain’t got nothing against him,” illustrates his belief that they really weren’t hurting people, just the banks that so coldly took people’s farms and livelihoods. Linking the 1930’s desperation with the 60’s sense of corporate oppression and overall distrust of ‘the man,” the film makes a statement about the present through an illustration of the past. No, there weren’t bandits roaming the prairie robbing banks in 1967, but the questioning of authority was clearly in the zeitgeist. Screenwriters Newman & Benton called the attitude “the New Sentimentality,” which referred to the very Sixties idea of putting personal needs ahead of the collective good and praising style over substance. In the case of Bonnie & Clyde, then, and how they appealed to not only the writers, but to the moviegoing public, it can be said that their exuberance & kinetic appeal far outpaced their actual skill. They were, frankly, quite poor bank robbers, choosing opportunity over profitability, but doing so with panache and style. The writers looked to Truffaut & Godard as creating art for beauties sake, putting the style of their productions over the substance of story. That wouldn’t overtly fly in Old Hollywood films, but the championing of the idea would be a breath of fresh air for New Hollywood. Championing a radical idea as the basis for a studio film not surprisingly caused numerous problems for the film, most notably in the fact that every studio and several independent producers all turned it down, some multiple times. Arthur Penn himself refused to direct it at least three times & an oft repeated, but false story, had Beatty, who assumed producer responsibilities, of actually getting on his hands and knees to kiss the boots of Warner Bros. chief Jack Warner. While Beatty never went to that length to get the film made, he struggled to get it made, ultimately settling on a relatively small budget of $1.6 million dollars, a little more than half of what the typical studio picture cost at the time. The chief argument in rejecting the film was the widely held industry belief that no one would sit for 2 hours watching despicable characters murder their way around the Southwest. Warner himself rejected the film repeatedly based on what he thought was a tired gangster genre that was the foundation of the studio’s growth in the early ‘30’s. While the Hollywood establishment couldn’t see the potential in the film, the creators of style over substance circling the film with interest. Newman & Benton, in a momentary fit of delusion, actually pitched Truffaut to direct the film and he initial accepted, before begging off, saying “..of all the scripts I’ve turned down in the last 5 years, Bonnie & Clyde is the best.” (Harris, p. 65) While the script would eventually receive an Academy Award nomination, it clearly wasn’t the calling card Beatty had hoped it would be. On the surface, the studio brass turning down the film were probably partially correct in their old school way of looking at the material. Bonnie & Clyde were minor criminals and the finale was a foregone conclusion. They could not see the style icon Bonnie would become, as Dunaway’s costumes became a fashion sensation, just as they couldn’t see the immense appeal of its 2 lead actors. Beatty had been a sensation in 1961 for his screen debut in Splendor in the Grass, but had largely floundered since in a string of artsy failures. Dunaway had a couple of films made, but not released, and was completely unknown. Similarly, due to budget constraints, Gene Hackman, Estelle Parsons & Michael J. Pollard were all chosen in part because they could be cheaply hired. All five of the actors would go on to Oscar nominations, or in Parsons’ case, an Oscar win. Little of what the film would become on screen was apparent in the screenplay, even though it closely resembled the final product, albeit with daily rewrites by Penn and input by Robert Towne. What does come through on screen, from the initial scene, is a tone that separates the film from the traditional Hollywood fare that came before it. It could be lighthearted and literally deadly serious, both in the same scenes. The genius of the film is the whipsaw manner of presenting almost comical moments punctuated by an extreme violence that had never been seen in American movies. The humor of C.W.’s parallel parking troubles immediately leading to the death of a bank employee or the quiet hominess of the apartment interrupted by the hail of gunfire when the police close in create the inability of the viewer to relax, drawing them into the life of outlaws on the run. There is senseless killing, often without apology, but it’s 2 minor characters who fundamentally reflect the tone of the film as one of foreboding inevitability, the undertaker (Gene Wilder) and his girlfriend Velma (Evans Evans). The swing of emotions from the time the Barrow Brothers steal the car, to Eugene chasing & threatening the gang, the gang chasing Eugene, the couple in the car with the gang & finally the revelation of Eugene’s occupation runs the gamut from slapstick comedy to sheer terror and finally resignation as Bonnie throughs them out of the car. It’s interesting that Robert Towne’s most significant contribution to the film was the placement of Velma & Eugene’s scenes within the flow of the film. Newman & Benton’s script had the ominous foreshadowing coming after the visit to Bonnie’s family, but by moving the scenes ahead of the visit it casts a melancholy shadow over the picnic and gives Clyde’s wishful thinking about living by Bonnie’s mother a greater poignance than even the mother’s line “you try to live three miles from me and you won’t live very long, honey. You best keep running, Clyde Barrow. And you know it.” Director Penn added to the written and foreshadowing elements of the tone by insisting that the violence hurt not just the characters, but the audience as well. The action must viscerally convey pain, suffering, death and most importantly, the escalation of violence that would culminate in Bonnie & Clyde’s own death. This, I feel, is Penn’s most important addition to the film; the calculated building of blood & gore as the film progresses. As one of the first American films to show the impact of a bullet meeting flesh (past films demanded a cut between shooting & impact), Bonnie & Clyde eased the viewers into the escalation by first having nameless victims suffer injury and death. The aforementioned butcher is black and blue, the bank employee shot in the face, the nameless policemen flail and fall, it’s really not until Buck & Blanche are injured that the reality hits home. Buck’s mortal injury is gruesome and bloody, while Blanche’s renders her an invalid, smited by the God she betrayed. All of this, of course, leads up the final scene that was deliberately shot as a ballet of violence and death. Because Penn used 4 cameras with varying film speed, he was able to deconstruct time to accentuate the carnage of the scene, at one point utilizing a prop hair piece on Clyde to simulate the death of President Kennedy. Penn used nearly 60 separate shots in less than a minute (Harris, p. 256), resulting in a scene that seems to play out much longer than it actually does. The impact, however, lasted even longer and has influenced directors as influential as Sam Peckinpah, Quentin Tarantino & Oliver Stone. It’s the finality of the matter and the quiet after the carnage that stays with the viewer.

The biopic is a tricky thing. Too much truth and the story can be diluted. Too little truth and it loses relevance. Arthur Penn’s Bonnie & Clyde captures the purity of that combination, raising its subjects to icons, while wonderfully illustrating their humanity and fallibility. That is was also able to debut a new beginning in American Film has certainly added to its historic importance, commenting on larger issues than the fate of 2 bank robbers who lived a brief and violent life nearly 90 years ago. Is it 100% accurate? Of course not, but its essence captures the spirit of the truth, the facts of their demise & the importance of their legacy. Sources: Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of New Hollywood. Mark Harris. 2008. The Penguin Group. Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-And-Rock ‘N’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood. Peter Biskind. 1998 Simon & Schuster. The Lives & Times of Bonnie & Clyde. E.R. Miller. 1996. Southern Illinois University Press.

1 Comment

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

- Anatomy of a Murder Notes

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed