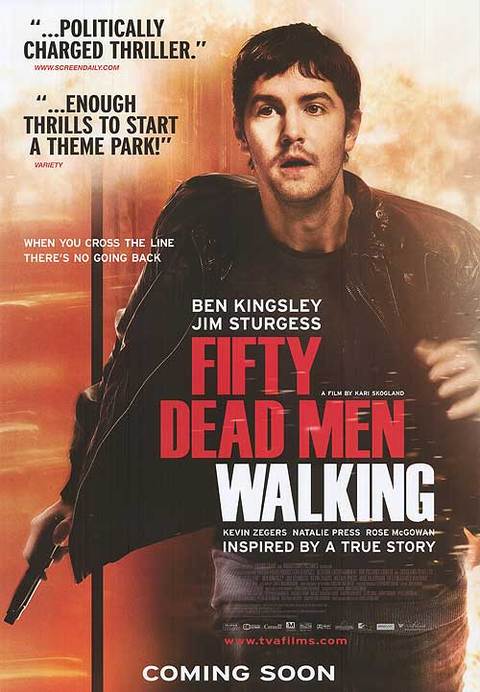

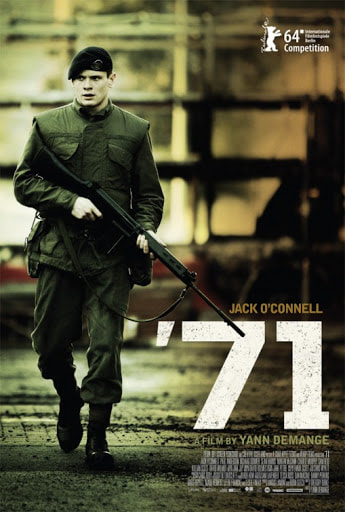

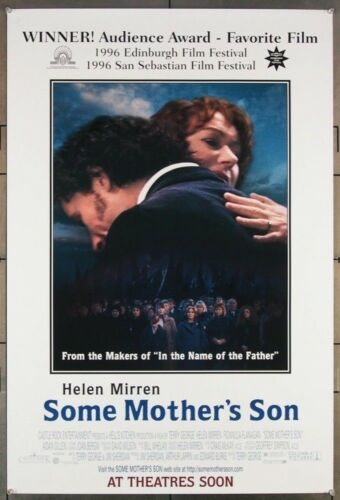

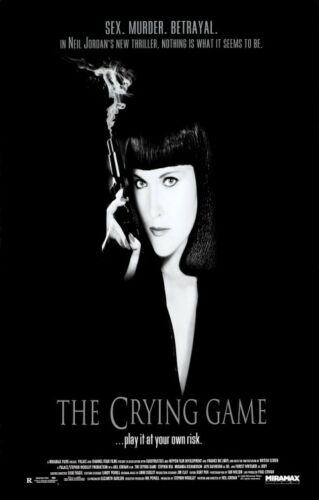

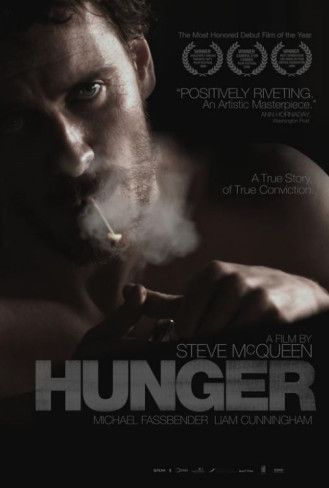

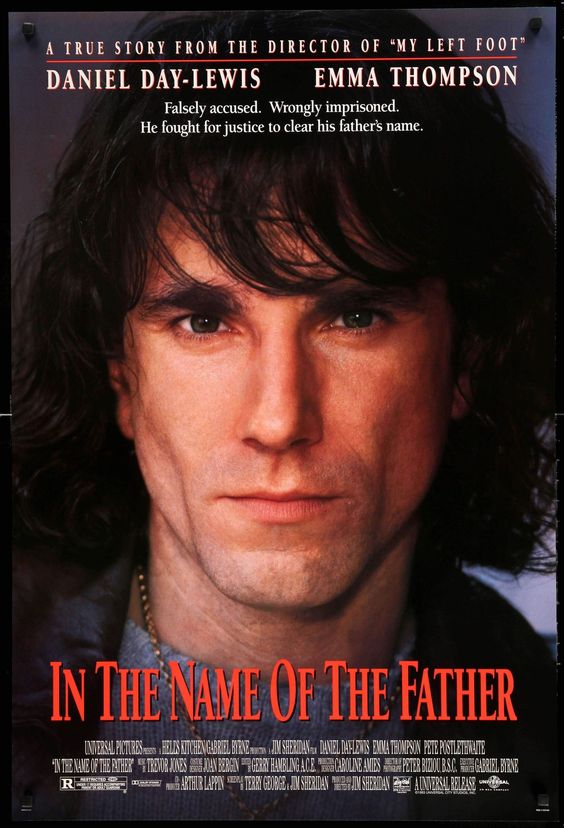

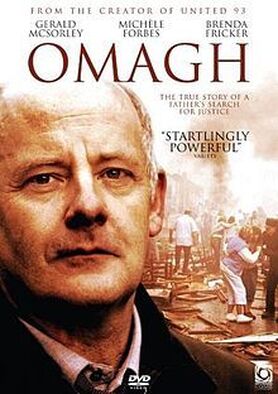

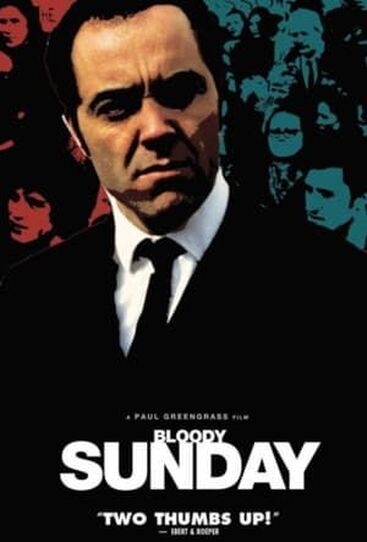

For most of the 20th Century the I.R.A. fought the occupation of Northern Ireland, but by the late 1960’s their influence, organization & efforts had largely waned. Instead, a non-violent civil rights movement, modeled after the movement in the United States, had grown in influence & importance. Peaceful protests & marches for fair treatment in housing, jobs & representation of the Catholic minority took place all over Ireland, but when they were met with violent resistance from Protestant paramilitary groups & offered no protection from police, the IRA gained membership & began a violent campaign that lasted nearly 30 years…The Troubles. In chronicling The Troubles on film there are conflicting points of view, perspectives & objectives utilized by filmmakers, but what becomes very clear is that most films are literally created through the lens of the British & American film industries by non-Irish filmmakers. Most of the films deal not with the origin of The Troubles, nor the underlying sectarian divide, but with the British government’s response, the futility of the entire endeavor or the inevitability of the Irish experience. Viewing nearly 30 films created over the last 40 years allows for the revelation that while the IRA was routinely vilified during The Troubles, & did perpetrate many atrocities in the name of unification, it was the systematic brutality of the British government & its security apparatus that must shoulder the greatest condemnation when looking back at The Troubles. From the far-fetched idea that The Troubles were carried out to help overthrow the Labour Party government in Britain in the ‘70’s (Hidden Agenda-1990) to several films showing the aggression of the military (Bloody Sunday-’02) or the duplicity & complicity of British intelligence services (The Miami Showband Massacre-’19), the British government is represented, mostly by British filmmakers, as being the single driving force energizing the killing, maiming & destruction of Northern Ireland. Innocent people are imprisoned (In the Name of the Father-’93) & prisoners are left to starve themselves to death (Some Mother’s Son-’96, Hunger-‘08) in filmic recreations of actual events, which in most cases make for more incredible & interesting films than the purely fictitious films on the subject (The Crying Game-’92, Patriot Games-’92, The Devil’s Own-’97). 10. 50 Dead Men Walking (2008) Directed by Kari Skogland The true-life story of RUC tout (informant) Martin McGartland, who rose to a position of leadership in the IRA, while simultaneously providing Ulster police with intelligence on the IRA. Based on a book McGartland published, the film attempts to paint both sides as equally responsible for the violence in Northern Ireland, using the same coercive language and rationalizations to maintain McGartland’s dual role. A particularly interesting stretch of the film has his RUC handler & IRA intelligence both explaining the opponents interagation techniques & how to act accordingly to thwart them. When British intelligence, in the form of MI5, take over an operation McGartland has informed on, however, McGarland is exposed & must go into hiding. It’s as if McGartland’s story is one of equal pain & suffering on both sides, playing both against the middle, until the Brit’s upset the balance, which is made clear when McGartland tells his handler in a moment of rage “why don’t you get out of my country.” 50 Dead Men Walking, which refers to the estimated number of people McGartland’s intelligence saved, paints a bleak picture for an informant, trapped by both sides, and made to do things against his nature, but never uses false suspense to manipulate the audience. Director Skogland, famous for her many TV directing assignments, does a fantastic job of keeping the tone of the film consistent as it moves from RUC to IRA, while mixing in a heavy dose of personal stress to create a 3 prong pull on McGartland. Jim Sturgess, as McGartland, & Ben Kingsley his RUC handler & both are stellar as are Natalie Press as McGartland’s girlfriend & Rose McGowan as an IRA Mata Hari. 9. The Boxer (1997). Directed by Jim Sheridan. Daniel Day-Lewis plays Danny Flynn, a boxer & former IRA soldier, recently released after 14 years in prison. He returns to Belfast to re-open a non-sectarian boxing club, but becomes embroiled between the military & political leaders of the local IRA. Using The Troubles as a backdrop, then, The Boxer emphasizes ‘home’ as the driving narrative force. Danny’s disdain for the violent tactics & moralistic codes of the IRA put his life at risk, but undermines the complexities of The Troubles. ‘Home’ becomes defined as an incestuously small area of Belfast, where everyone & everything is constantly watched from above. Emily Watson plays Danny’s teenage love interest, now married to his imprisoned best friend, but still in love with Danny. Their illicit love, in fact, further constricts the space of the film & leads to an improbable final scene. In terms of The Troubles, The Boxer sets up the 2 sides of the IRA that had become apparent by the mid-nineties, the political, looking for a peaceful settlement, & the violent, willing to continue the fight by any means necessary. A suspension of disbelief scene bringing together prominent Loyalists & Republicans, joined together to cheer on Danny’s boxing match, devolves into an all-out riot & undermines the 25+ years of armed struggle, reinforcing the political relevance of the peace negotiations that were still ongoing when the film was made. 8. Hidden Agenda (1990). Directed by Ken Loach Ken Loach is an award-winning director socially aware films like Poor Cow (1967) & Rif Raff (1991), so it’s no surprise that he took on the Troubles with his 1990 film Hidden Agenda. Wrapped around the story of an American human rights attorney’s disappearance, Hidden Agenda looks at British Intelligence’s role & the political implications of the escalation of violence in Northern Ireland during the ‘70’s. Taking the position that decisions on the nature of the violence were made at the highest level of government, Loach & screenwriter Jim Allen (Land & Freedom ’95) create a conspiracy thriller that intimates the ‘overthrow’ of the British government. The film brilliantly brackets the position of the British government & its security forces in both the opening of the film, where Prime Minister Margret Thatcher reiterates that the people of Northern Ireland are British subjects, & the end of the film the unchecked power of the intelligence services to dictate & control policy within Northern Ireland. Loach’s film is certainly provocative, and like several other films, both reality-based & fiction, the Hidden Agenda does indict British Intelligence as the driver of violent escalation during the ‘70’s & ‘80’s. Frances McDormand & Brian Cox, as the widow & a English police detective, respectively, do a fine job unwinding the serpentine mystery of the disappearance & murder & bring a certain gravitas to Loach’s Palm d’Or nominated feature. Paired with the documentary The Miami Showband Massacre (2018), the depth of British Intelligence’s footprint in Northern Ireland becomes even more haunting. 7. ’71 (2014) Directed by Yann Damange Director Demange’s (White Boy Rick-‘18) feature debut borrows much from Carol Reed’s classic Odd Man Out (1947). Whereas a wounded IRA man (James Mason) is stranded in Loyalist neighborhoods as the police track him after a botched robbery in Reed’s film, ’71 has a British soldier trapped in Republican neighborhoods & pursued by paramilitaries during a long night at the height of sectarian violence in Belfast. As England increased its troop presence in Northern Ireland in response to violent IRA bombings & attacks, the soldiers became younger & mostly without the proper training & experience to handle urban guerilla warfare. The taut 99-minute film paints a vivid picture of the root of escalating violence during 1971, when nearly 500 people died, showing the hair trigger nature of violent clashes between civilians & soldiers. Jack O’Connell (Unforgiven ’14) stars as recent recruit Gary Hook, who becomes lost in the close quarters of the mixed neighborhood, only to be led to temporary safety by a young Protestant boy. When a British Intelligence bomb explodes prematurely, Hook is injured & disoriented & finds shelter in the home of Republicans. Throughout the night he is pursued by an IRA hit squad, while he tries to make his way back to safety. The film does a great job of showing the randomness of life & death in Belfast during the early years of the Troubles. This film was probably the biggest surprise in the movies I watched & is well worth the time. 6. Some Mother’s Son. Directed by Terry George The 1981 hunger strike that killed 10 IRA prisoners in Long Kesh prison drew worldwide attention when it unfolded during that spring & summer. Bobby Sands, the first to go on strike (March 1st) & the leader of the IRA prisoners, was the most famous of the strikers & the first to die. While Steve McQueen’s film Hunger placed Sands at the center of his more intimate film, Terry George, who also wrote In the Name of the Father & The Boxer, uses Sand as a guiding force for the strikers, but fictionalizes the story of 2 strikers & the impact the strike had on their mothers. Helen Mirren stars as Kathleen Quigley, the mother of a fictional IRA soldier & cell-mate of Sands, exists in an apolitical world & struggles to understand the Republican movement & her son’s part in it. As she is swept into the movement by a hardcore Republican friend, she begins to understand the prisoners’ plight, as well as the overarching issues within the struggle. Some Mother’s Son shifts the emotional heft of the Troubles to the peripheral victims, the families, to show a broader impact. The emotional impact is tempered, however, by the fictional account, but Mirren’s performance, as well as Fionulla Flanagan’s, as her friend, are wonderful & occupy the emotional center of the film. Some Mother’s Son is a Hollywood version of the hunger strike, although still quite impactful, but it misses the stunning visuals of Hunger & the immediacy of the realities of strikers’ deaths. In making it broader, however, the film illustrates the ripple effects that believers or citizens alike must face while living in a war zone. 5. The Crying Game (1992). Directed by: Neil Jordan Jordan’s Academy Award winning film has as its framework the kidnapping & death of a British soldier at the hands of a team of IRA soldiers, but it’s really a multifaceted love story with a reveal that made it a novelty. Sadly, the secret masks a well-made & thoughtful film about emotional connections, grief & regret. Fergus (Spephen Rea) is a reluctant militant, who is tasked with killing British soldier Jody (Forrest Whitaker), then fleeing to London where he seeks out Jody’s fiancé Dil (Jaye Davidson). I think the most important element where the Troubles are concerned is in its depiction of the IRA soldiers, including leader Maquire (Adrian Dunbar) & Jude (Miranda Richardson), who represent the blind commitment to the cause & the more thoughtful & caring Fergus. Sligo born Jordan wants to give nuance & sensitivity to his protagonist (Fergus), but in doing so he falls into the trap of painting IRA members as either all good or all bad. Even Jody’s death leaves Fergus largely blameless & his growing affection for Dil leads to self-sacrifice & imprisonment. He is good, we get that. Maquire & Jude are bad; they indiscriminately kill & put cause before friendship, which I guess should be a soldier’s attitude, but they are 1 dimensional characters & that is the film’s one flaw. 4. Hunger (2008). Directed By: Steve McQueen Watching Steve McQueen’s 2008 film Hunger is a visceral & emotional experience. Aside from one long scene between IRA hunger striker Bobby Sands (Michael Fassbender) and his priest, there is very little dialogue of any kind. Sound is so precious that when the prison guards line up behind shields in their riot gear, the abrasive & rhythmic bang of their batons momentarily shatters the mundane nature of the prisoners’ lives living in filth. That the ritualistic beatings & abuse that follows seem inevitable & routine only heightens the despair in watching it. Hunger is the story of the 1981 Irish Republican Army protest for prison of war status in a Northern Ireland jail (Long Kesh). The hunger strike at the center of the film evolved out of a 4-year long ‘dirty protest’ where nearly 400 prisoners first refused to wear prison clothing, using only blankets for cover, then refused to use chamber pots, smearing their excrement on their cell walls & dumping urine into the hallway floors. Bobby Sands, the leader of the prisoners, was the first to begin (Mar 1, 1981) his hunger strike & eventually died on the 66th day of his strike, the first of 10 strikers to die. McQueen’s camera does not shy away from depicting the outrageous conditions the prisoners lived in, including maggots, feces-stained walls & urine squeegeed up along endless corridors. Small victories are visually recorded like the creative passing of notes & small radios with visitors or the prisoners’ use of their weekly mass to socially engage, while ignoring the priest. McQueen divides his film into 3 parts & aside from 2 scenes, captures the story within the walls of the prison. The first third sets up the conditions of the prisoners in their cells during the dirty protest, as well as their horrific treatment by the guards. The middle third is the long scene between Sands & his priest (Lima Cunningham) where they banter about the value of a life. McQueen likened the scene to a tennis match with Sands the aggressor & Father Dominic volleying back to dissuade the risk of life. Shot with just a few cuts, the scene is a tour deforce of resolute beliefs on both sides & grounds the 3rd section of the film in both the reality of Sands’ undertaking, the confidence in his beliefs & the understanding that he knows he will die. Finally, the third section chronicles Sands’ decline as he moves through the strike, complete with dreamlike hallucinations, the painful reality of starvation & the emotional impact of a life slowly ebbing away. Fassbender’s performance is unforgettable & McQueen’s images perhaps capture the reality of death better than anything I’ve ever seen on film. 3. In the Name of the Father (1993) Directed by: Jim Sheridan In the Name of the Father is the true story of the Guilford 4, alleged IRA bombers falsely imprisoned for more 15 years for the bombing of a pub in England. Writer Terry George & director Sheridan put the relationship between alleged bomber Gerry Conlon (Daniel Day-Lewis) & his father Giuseppe (Pete Postlethwaite), who was also convicted of conspiracy, at the center of the film, but the real story is the complete indictment of the British legal system. Many British critics of the film focused not on the gross miscarriage of justice, but on the literary license George & Sheridan took with the story’s details, including how the key piece of evidence that freed the prisoners was discovered. Creating an arc of Gerry’s evolution from petty criminal in Belfast, to indifferent prisoner & finally advocate for his own freedom, In the Name of the Father is a morality story, instead of an overtly political one. Gerry’s eventual realization that his father’s stoic resolve is more meaningful than violence is the center of his growth within the film, but it comes the cost of driving the political message of the injustice done to the prisoners & their families. The indictment of the British legal system is secondary, but does provide the climactic punch in the courtroom. Sadly, the road to that scene is given short shrift from the larger perspective of systemic corruption, but the emotion of the scene lifts the film & allows a more redemptive conclusion. On the whole, however, the film brings attention to a horrific story, as well as allowing for enough information on the British government’s reactionary complicity in injustice to make it one of the best on the list. 2. Omagh (2004) Directed by: Pete Travis The 2004 film Omagh tells the true story of the city center bombing in the Northern Irish town of Omagh on August 15th, 1998, nearly 4 months after the Good Friday Peace Accords had been signed. The bomb killed 29 people, injured another 200 and was perpetrated by a splinter IRA group, called the real IRA, that was upset with the peace agreement. The film centers on several of the victim’s families, primarily Michael Gallagher (Gerard McSorley), father of 21-year-old victim Aiden Gallagher, as they work through their grief, while also pressuring the local authorities to investigate & capture the perpetrators. While all parties condemned the bombing and nearly 100 people were eventually arrested, no one has ever been convicted of the bombing. The importance & brilliance of the film is in the way in which it depicts grief in its many forms. McSorley is fantastic as a father driven towards justice as a means of gaining peace, who evolves into an outspoken leader of the family advocacy group. Michele Forbes plays his stoic & stricken wife whose silent suffering grounds the Gallagher household. As the fruitless investigation continues it becomes clearer that the equal justice promised under the peace accords may not have been instituted in Omagh, when it becomes clear the RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary, the historically sympathetic Protestant police force) ignored warnings, mishandled evidence & covered up errors. Omagh is a wonderful film that eloquently captures the lingering issues in Northern Ireland involving police bigotry & complicity, the importance of the peace agreement at all costs & the immense human toll that The Troubles inflicted on ordinary people. 1. Bloody Sunday (2002). Directed by Paul Greengrass

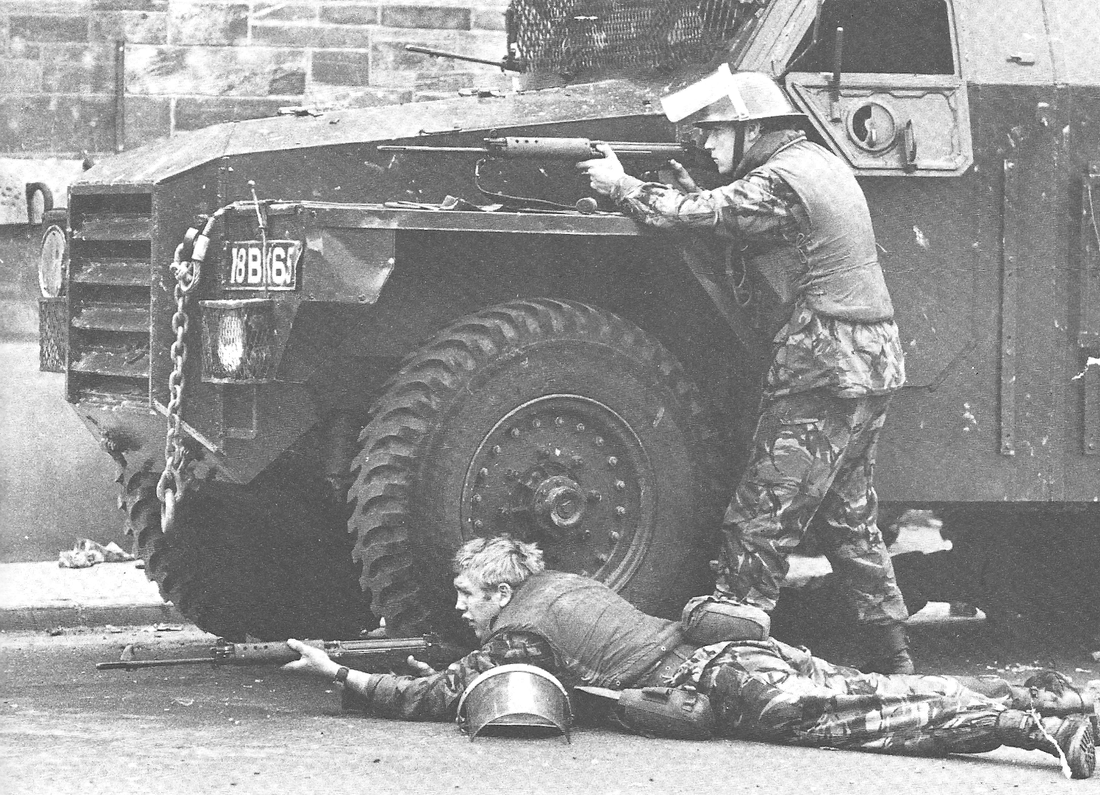

Greengrass’s film takes the top spot on the list because it captures several of the overriding themes of the Troubles & distills them into one seminal event, the Bloody Sunday/Bogside Massacre that happened in Derry, Northern Ireland on January 30th, 1972. Made famous by U2’s song Sunday Bloody Sunday, the event, where 13 unarmed & peaceful protesters were killed by British paratroopers, has long been viewed as a touchpoint for Republicans in Northern Ireland. Greengrass’ film reflects the chaos & flashpoint quickness that signified daily clashes between Republicans, often normal citizens, & the British military. It also captured the disdain the British military felt for the Irish & the military’s seemingly intentional desire to escalate those confrontations. Created in documentary fashion, the film has an immediacy that places the viewer within the march organizer’s chaotic lead up to the march, as well as the British intelligence command center. On both sides there is a clear helplessness to stop the massacre as it unfolds, but Greengrass places the blame on the military leadership in the field, who saw the marchers as an angry mob & set out to settle old scores with the people of Derry. As in ’71, Bloody Sunday makes it clear that the soldiers deployed during the Troubles weren’t trained to fight a guerilla war, in an urban setting, against people who were supposed to be their fellow citizens. Bloody Sunday was a tragedy that was largely unnecessary, but the final point that Greengrass makes, which resonates throughout the films of the Troubles, is the complicity of the Northern Ireland & British governments to either cover up or deny atrocities like Bloody Sunday. The loss of life in the actual event is tragic, but Bloody Sunday does the best job of reflecting the Troubles, while honoring those dead. For a thumbnail understanding of the overall tragedy of the Troubles, then, one should start with this film, then continue on for various events & ideas that color how most people understand them.

0 Comments

|

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

- Anatomy of a Murder Notes

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed