|

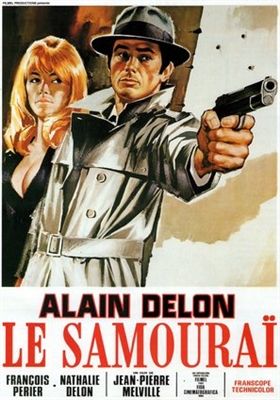

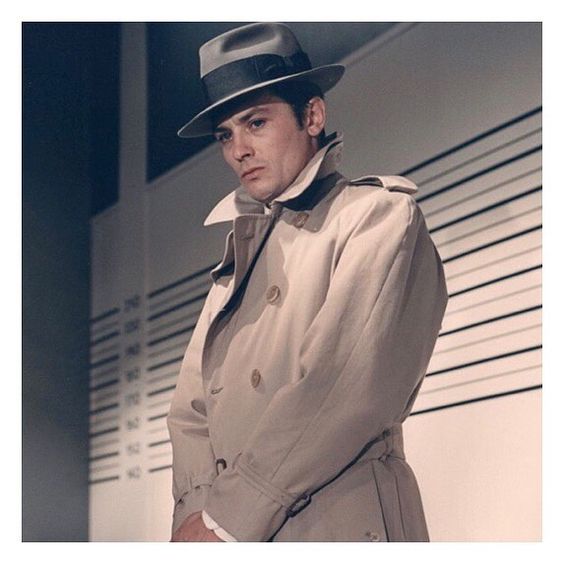

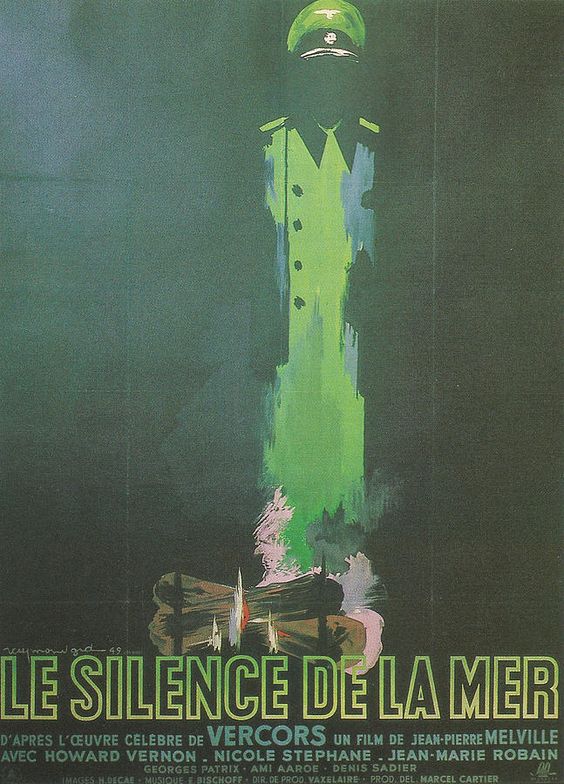

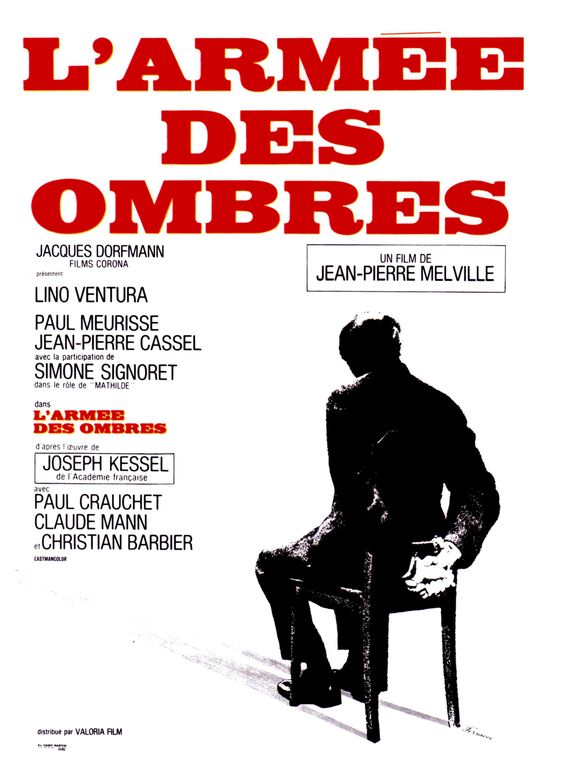

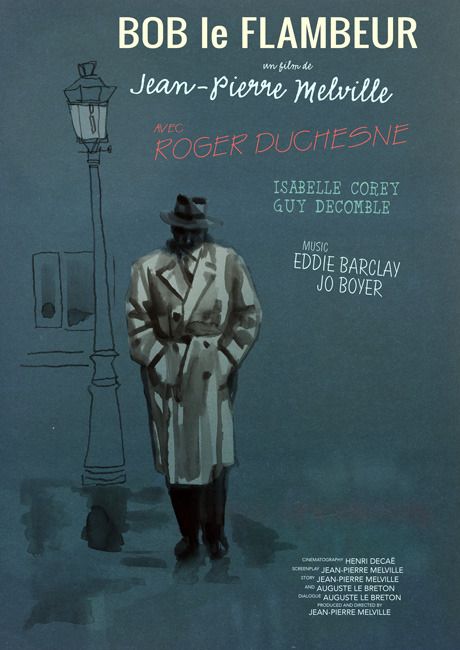

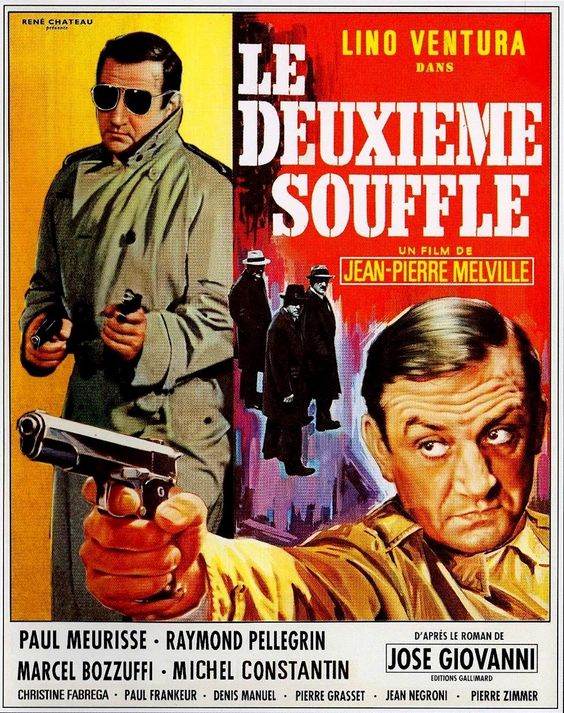

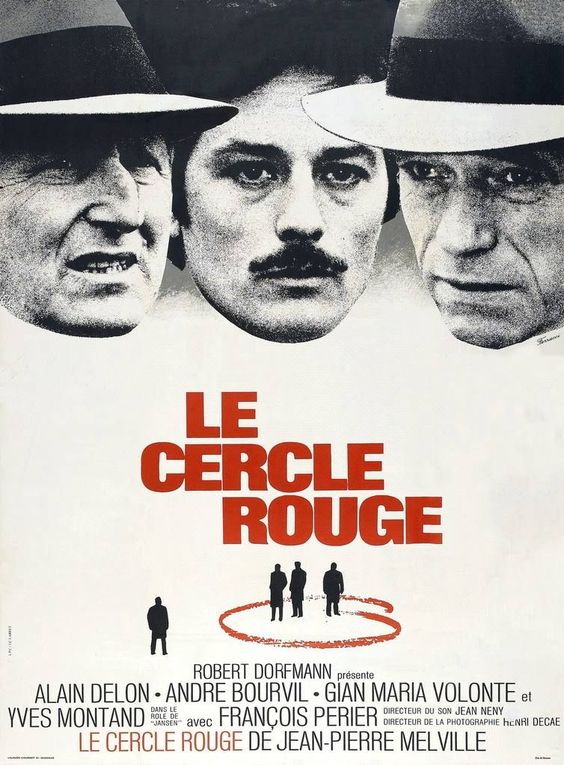

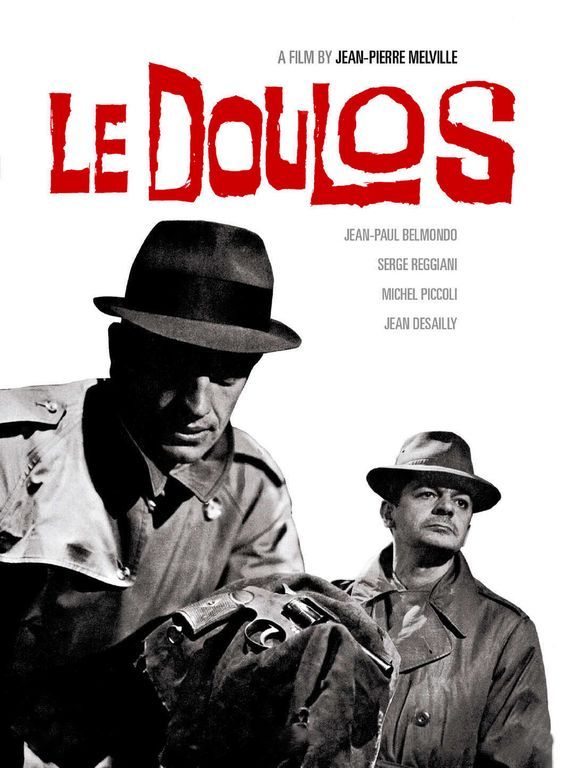

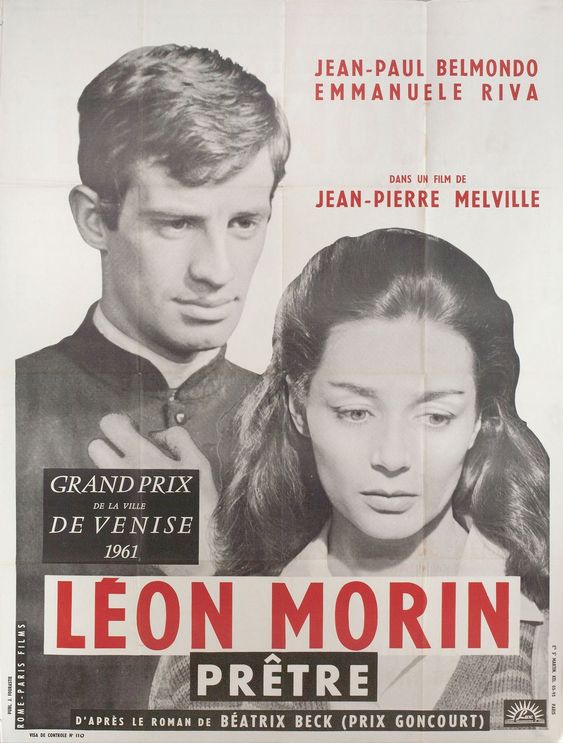

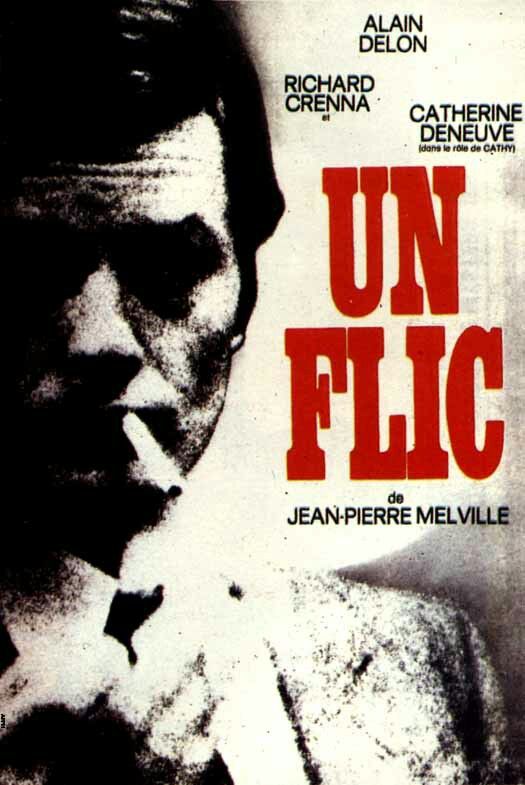

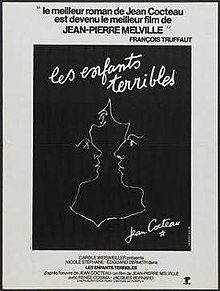

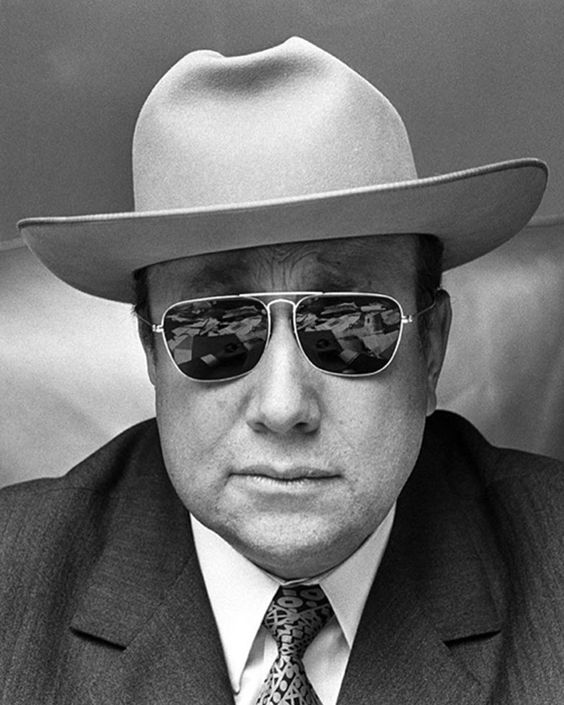

The Rationalization: Jean-Pierre Melville was a French director who is often called the godfather of the French New Wave (Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, et al) due to his use of location shooting & producing his films outside of the French film industry’s mainstream on shoestring budgets. The New Wave’s journal, Cahiers du cinema, heaped praise on Melville throughout the 50’s, while at the same time identifying & extolling the virtues of American autuerists like Howard Hawks & John Ford. That Melville, also cited as the first great cinephile director, grew up on American films of the 30’s & 40’s & revered director like William Wyler (The Best Years of our Lives, Mrs. Miniver, The Letter) & Robert Wise (Born to Kill, The Set-Up, West Side Story) only enhanced Cahiers belief that Melville was the French bridge to creating a new form of cinema, taking what was great about the autuers who worked within the studio system & moving film into the streets. Melville’s body of work, just 13 feature length films, made over a period of 23 years, belies his impact on both French & world cinema, having impacted directors as diverse as John Woo (The Killer-89, Bullet in the Head-90 & Mission Impossible 2-2000), Volker Schlondorff (The Tin Drum–‘79, The Handmaid’s Tale-‘90) & Quentin Tarantino (Reservoir Dogs-‘92, Pulp Fiction-’94). While he is best known for the 6 Noir gangster films made from 1956 to 1972, Melville also made 3 very important & more personal films about the French Resistance during World War II, having participated in the Resistance beginning in 1943. All his films, however, portray a world that is constructed of personal isolation, whether a killer, a thief, a war widow or a billeted Nazi officer, but thrives on codes of honor & behavior that often cost his characters their lives, a chance at love or a chance at redemption. Le Samourai (’67), while not his last masterpiece, is the culmination of the Melvillian aesthetic of stoicism, solitude & an undying belief in a moral code inhabited by an immoral or amoral protagonist. The film is as near to perfection as a film can come to reflecting cinematic greatness, while at the same time reflecting the artists true vision. Alain Delon plays master hitman Jeff Costello, a character based loosely on Alan Ladd’s performance as Raven in 1942’s This Gun for Hire, but Melville & Delon distill the killer to an emotionless cypher, alone & trapped as the world crashes down around him. Melville, in fact, lured Delon to take the part by reciting the opening scene & after 10 minutes of storytelling Delon noted that not a word was spoken & immediately accepted the part. Methodical down to examining the placement of the brim of his hat, Jeff is witnessed killing a nightclub owner on contract & must contend with both the police & the gangsters who hired him to remain free & alive. Seemingly his only relationship is with a caged bird, a metaphor that becomes more blatant as the story unfolds. Melville’s muted color palette, accentuated in the opening scene of Jeff’s depressing apartment, and hypnotically paced scenes allow the viewer to focus solely on Jeff as he acts & reacts, always with a plan. The killer’s code is evident in everything Jeff does & reflects Melville’s unwavering disbelief in human nature, unless it’s governed by rules & beliefs; beliefs that carry on up to & through the final surprising frames. Melville’s first feature, Le Silence de la Mer (The Silence of the Sea ‘49) was based on a classic novel of the French resistance that was published clandestinely in 1942 & distributed throughout WWII. Living in London in 1943 & involved in the Free French movement, Melville came across the book & immediately decided it would be his first feature, even though he had never made a film of any kind. That he had no money, nor experience, did not deter Melville & the fact that he did not own the rights to film the story, only offered an afterthought as he pieced together film stock ends to shoot the film as money permitted. When Vercors, the alias for writer Jean Bruller, denied Melville the rights to film his novel Melville struck a grand bargin: Vercors could have a jury of resistance fighters of his choosing to judge the film. If even 1 voted against the film Melville would personally destroy the negative. Thankfully, the jury agreed that the film fairly represented the novel & the film was released. Le Silence de la Mer is the story of an old man & his niece who make the conscience decision to ignore the billeted Nazi officer who shares their home in occupied France. As the story unfolds, the uncle only communicates in voice over narration, while the officer spends every evening in the small parlor giving monologues about his love of France & the French & his belief that a combined country, overseen by the Germans would be a positive step for humanity. As the months draw on, his monologues become more personal, even as the French remain stoically silent, each of the 3 existing quietly in their own heads. Only when the officer spends time on leave in Paris does his attitude change & force him to request another assignment that will change his life. Melville’s early film is a masterclass in mood & perception, driven by the subtlest gestures & words left unsaid. It is both sad & tragic, but a wonderful reflection on the individual resistance that exists in every soul & perfectly reflects the strength of the French people under the horrific realities of the Nazi occupation. While Le Silence de la Mer was Melville’s debut, Army of Shadows (’69), also about the French Resistance, was the masterpiece that was the capstone of his career & a perfect conclusion to his trilogy of resistance films. Focusing instead on the inner workings of resistance fighters, Army of Shadows is based on the novel of the same name & fictionalizes actual heroes of the Resistance. Lino Ventura stars as Philippe Gerbier, who earlier starred in Melville’s Le Deuxieme Souffle & didn’t talk to the director throughout the shoot, is the leader of a resistance network charged with sabotage & escape. Ventura’s hulking presence & quiet & calm demeanor lends gravitas to everything the resistance executes, whether it be a daring escape, routine sabotage or clandestine maneuvers (like parachuting into occupied France). Similarly, Melville is at home mixing his love of the intricacies of a good heist, with the spirit de corps of the fight against the Nazis, even if it means showing the brutality of war & fluidity of trust. As with many of his other films, the unspoken code of honor that exists within the group portrayed reflects Melville’s belief that society exists with a series of rules, that vary by group or by individual, but it is only through strict adherence that success can be achieved. The all-star cast includes Simone Signoret (Diabolique), Paul Meurisse (Diabolique) & Jean-Pierre Cassel (The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisis). Army of Shadows opens with a Nazi brigade marching past the Arch de Triumph, complete with a military band; a feat only Melville’s fame & power could have pulled off. At the time of the film’s release, however, Melville drew a great deal of criticism from reviewers who thought the film a naïve portrayal of De Gaulle & his politics. Because of this, the film was largely pulled from release & by the early 2000’s there were no complete prints in existence. In 2006 a complete restoration was created using VHS copies, existing pieces of the actual film & modern technology & the film finally was released worldwide to great acclaim. The next 4 films are essentially ranked in random order as they represent, along with Le Samaurai, the core of what Melville is known for; the gangster Noir film. Today I have Bob Le Flambeur (Bob the Gambler ’56) ranked first because it’s the film that started Melville’s Noir cycle. While the classic era in Film Noir in America is generally said to have been from 1942-1958, Melville was able to both distill down the elements of the movement, as well as add new & exciting twists. The movement itself had just recently been identified and named Film Noir by French critics & there was still much fluidity in its definition. What Melville did with Bob Le Flambeur was twist traditional American leading man iconography into a pretzel by using a middle aged, not very good looking & not very famous actor as his leading man. Roger Duchesne’s best work had been in the 1930’s, but Melville outfitted him in what would become his leading man’s signature look, the tan trench coat, tied at the waist, with a narrow brimmed hat, placed just so on the head. Duchesne’s Bob is a career criminal and a degenerate gambler who exists with a code of conduct that has made him somewhat of a legend in criminal circles. He protects a former partner’s son; he won’t help a pimp who beats his girls & he saved a cop by deflecting a bullet because it was the right thing to do. When Bob loses big at the casino he comes up with a complicated plan to rob the casino with a small group of hoods, organizing them like a commando unit attacking a military stronghold. Melville’s cool color palette & detached & generally emotionless leading man harkened back to the hard-boiled B movies of 1940’s Hollywood, but placed them in a morally coded world driven by reflexive and hyper mannered behavior, where any deviation, like Bob returning to gamble, has grave consequences. Bob Le Flambeur is the opening picture in a gallery of tightly scripted, calmly paced & brilliantly shot films that made Melville’s reputation & drew in countless imitators. Dubbed “Noir 2.0” by Marc Svetov*, Melville’s brand of Film Noir not only transposed the action from big city USA to Paris, France, but also placed the stories in often unreal settings where “…the gangsters wear American clothes & drive big American cars” (Svetov). His choices could be pointed to as being more about style than substance, but they always had a reason for being & Melville never wasted a shot, more often holding a shot slightly longer to capture the smallest gesture or feeling from his actors. Vino Ventura, in Le Deuxieme Souffle (The Second Wind ’66) was just the actor to capture Melville’s world-weary, but determined criminal. The film opens with a daring prison break where 2 of the 3 convicts are killed or captured, but the oldest & biggest escapes. What follows is a tricky game of cat & mouse as Gu (Ventura) tries to stay one step ahead of mastermind chief inspector Blot (Paul Meurisse), while plotting to re-enter the criminal world. Gu & Blot both live by the Melivillian code of honor & hold each other in high esteem, even as they look at the law quit differently. Whereas Gu chooses a life of isolation, but generates untold loyalty from his criminal friends & his long-suffering girlfriend Manouche (Christine Fabrega), Blot is often surrounded by other cops, but still holds respect for Gu. When Gu is drawn into an armored car robbery, Melville rachets up the tension in a virtuoso heist sequence on a winding mountain road. Executed with minimal dialogue, the scene plays out as a ballet of timing, violence and tempered success. The criminals get away, but it becomes clear that Gu is doomed, because in Melville’s world that is an anticipated outcome for simple mistakes, bad timing or just plain fate. Le Deuxieme Souffle was Melville’s highest grossing film to date & a critical hit, but signaled a shift with New Wave critics, who pointed to the film as Melville’s sell-out of principals & its overtones of “loyalty, heightened professionalism, solitude & betrayal” (Danks) were, in part of reflection on that shift. Le Cercle Rouge (The Red Circle ’70) is simply one of the greatest heist films ever made & once again Melville uses a well worn ‘genre’ to emphasize isolation, trust & professionalism. The heist scene that is at the center of the film is the equal to that from Rififi (Jules Dassin ’55) & The Asphalt Jungle (John Huston ’50) in its dedication to silence & emphasis on precision teamwork. If Le Deuxieme Souffle’s outdoor heist riffed on the armor car robbery in Criss Cross (Robert Siodmak ’49), then Le Cercle Rouge’s jewelry robbery took the foundation laid before in the 2 earlier masterpieces & built a high rise on top of them. Through a dizzying series of stairs, rooftops, electronic sensors & alarms, Melville has his team of criminals (Alain Delon, Yves Montand, & Gian Maria Volente) masterfully swoop in & meticulously breech all obstacles, including a marksman’s shot to disable an alarm. Jansen (Montand) personifies Melville’s isolated hero to a tee, but the director/writer moves him one step towards oblivion by making him a recovering alcoholic holed up in a box like room. By graphically showing the hallucinations that accompany his withdrawls & giving him the edge of an addict, Melville tempers & clouds his every subsequent action. Delon, on the other hand, is at his stoic best as Correy, the leader of the group, who picks up an escaped convict & sets the heist in motion. Just as in Le Deuxieme Souffle, however, Melville paints one of his most interesting characters on the good side of the law, here in the form of Police Commissioner Mattei (Andre Bourvil), a cat lover with a dogged sense of pursuit who is in everyway the mirror image of Jansen. They are lonely souls, world weary & jaded, who exist only to serve the code that defines them. Jansen is a former cop, so his relationship with Mattei is a moral struggle that elevates Le Cercle Rouge from being ‘just a heist movie.” If Alain Delon represents the dispassionate, yet straightforward, side of the Melville hero/anti-hero, then Jean-Paul Belmondo, playing a burglar of questionable scruples in Le Doulos (The Hat ’62), is the warmer, but seemingly ambivalent side. The title refers to Parisian slang for police informant & in the confusing & multi-layered plot Belmondo has the look of a rat all over him. Quentin Tarantino describes Le Doulos as having the best screenplay ever written, noting “for the first hour of the film the viewer has no idea what’s going on.” The confusion lies in determining whether Silien (Belmondo) is the informant & who he will betray next. The understanding of his motives are at the core of the film & directly leads to the tragic conclusion. Belmondo is all about movement & action, propelling the story forward with his actions, even if the viewer is not entirely clear of Silien’s or Melville’s motivations for him. Le Doulos is as Noir as it gets, with double crosses, triples crosses & murder, but it still exists within Melville’s code of behavior. The thieves exist within that code, but here the police do not, as they try to frame first Silien & then his friend & fellow thief Maurice (Serge Reggiani), who is at the center of the robbery that triggers the action. Trust is the basis for everything that happens in Le Doulos, whether it’s a cop, a girlfriend, a gangster or what we’re watching. In this case, the viewer has to trust Melville that he’ll tie everything together. If trust guides the story in Les Doulos, then faith is at the core of Leon Morin, Priest (‘61), the film made just before Les Doulos & the center film in his occupation trilogy. Barny (Emmanuelle Riva) is a widowed mother of a young girl trying to find sense in the world in occupied France during WWII. While, at first, there are sideways glances at the occupying Italian force, when the German come to town there are serious concerns that drive Barny to church to offer confession to a young priest, Leon Morin (Jean-Paul Belmondo). She tries to antagonize Morin into criticizing the Catholic faith & religion in general, but the priest only offers to help. In a series of meetings between the two there are discussions on the nature of faith, of God’s place in war torn France & of humanity itself. Morin subscribes to the ‘invisible church’ made up of all human beings of goodwill, but Barny only slowly begins to open herself to faith, at the same time falling in love with the priest. Melville’s simple execution of the story, with most of the film taking place in small rooms, focusses everything on the subject matter at hand, whether faith can exist in a living hell. If there is a struggle between faith and denial, can that struggle be greater than or equal to the struggle between collaboration & resistance? Here faith is shown as part of the greater code, the rules Morin lives by are pure & Barny must come to terms with that. Melville’s final completed film Un Fliq (A Cop ’72) has Delon flipping to the good side of the law as a workmanlike, but dogged detective after a group of thieves. Here Melville focuses as much on process as product by showing first a choregraphed bank robbery that goes awry, then a meticulous theft of a briefcase full of heroin from a moving train. The bank robbery ultimately results in 2 deaths, but it is the methodical layout before the blasts that is pure Melville as he shows the robbers enter the bank one by one, ratcheting up the tension without a word being spoken. The wounding of a robber & the death of a clerk shatters the tension & the gang flees with only part of the loot, which precipitates the need for the second, more daring train robbery. Commissaire Coleman (Delon) frequents the club of one of the robbers & is having an affair with his girlfriend Cathy (Catherine Deneuve), all the while trying to pin the robbery on the group. Just as Delon’s Jef Costello, from Le Samuarai, is shrewdly calculating, so too is Coleman, who coolly keeps his thoughts & emotions in check as he closes in on the gang. In a prolonged scene right out of a Bond film, the train heist starts with the leader of the gang Simon (Richard Crenna) being lowered onto the train from a helicopter, breaking into he train without detection, then disabling the heroin’s courier & escaping back to the helicopter, all while changing out of overalls & into a dressing gown & pajamas. It’s spy craft at its best & Melville wonderfully takes his time with the entire episode, right down to Crenna repeatedly checking & fixing his hair. Un Fliq’s tragic conclusion is punctuated by self-sacrifice, as once again the criminal code, coupled with sentiment, leads to death & just as in Le Samourai it is the girl who is saved, an innocent, kept at arm’s length of the banality of the criminal life. By naming the film “A Cop” Melville puts Coleman alongside wise & methodical cops like those in Le Cercle Rouge (Mattai), Le Deuxieme Souffle (Blot) & Le Samourai (Le Commissaire)& illustrates yet again that the code exists across both sides of the law. The final film in Melville’s top 10 is his interpretation of Jean Cocteau’s 1929 novel of the same name, Les Enfants Terribles (The Terrible Children ’50), which was only Melville’s second film. While Francios Truffaut (400 Blows ‘59, Jules & Jim ’62) famously noted that “Cocteau’s greatest novel has become Melville’s greatest film”, I don’t rank this any higher because the films greatness is often attributed to Cocteau. He was a constant presence on the set, at one point yelling “cut” mid-take, a move that precipitated Melville kicking him off the set. Les Enfants tells the story of Elizabeth & Paul, sister & brother & their all consuming relationship with each other. Elizabeth is protective of her brother, while Paul is sometimes abusive, but their obsessive relationship is built on games they play with each other, against others & for the amusement of themselves alone. It is destructive & creepy, but it allows them to wall themselves off from the outside world. Paul’s infatuation with schoolboy troublemaker Dargelos (Renee Cosima) leads to his being bedridden, further isolating him & binding him to Elizabeth. After the death of their invalid mother, Elizabeth goes to work as a model & brings home a girl who looks surprisingly like Dargelos named Agathe, also played by Cosima, with whom Paul immediately becomes infatuated. Elizabeth’s reaction causes tragedy & death & finalizes the game with neither sibling winning. I don’t know if Quentin Tarantino said it best when he explained Melville’s impact on him by saying, “His films were like he took the Bogart, Cagney, Warner Bros. gangster films…and he just gave them a different style, a different coolness, you know they had this French thing going through it…they had a different rhythm all their own”, but he certainly got to Melville’s essence & genius. It is the rhythm, the pacing & the deliberate Americanization of the French settings which make his films unique; an homage to the American/Hollywood tradition, but elevated &hyper-realized in a fantastical way. Basic behavior is sometimes not realistic & there are sometimes bizarre coincidences that drive the plots, but Melville’s style is instantly recognizable & somehow very modern. His films haven’t aged; they are as fresh & enjoyable today as when they came out. His code is universal & his films wallow in a strict structure that allowed him to look back towards Hollywood, while at the same time looking forward to the French New Wave. His brief, 14 film career, is as important as any director that came before or after & he is worthy of celebration.

Sources: “Jean-Pierre Melville: Film Noir 2.0”. Marc Svetov. Noir City Annual Summer 2011. Film Noir Foundation. “After the Fall…” Adrian Danks. Criterion Collection Liner Notes. “No Greater Solitude: 10 Years of Jean-Pierre Melville”. Imogen Sara Smith. Noir City Annual 2017. Film Noir Foundation. “Interviews: Quentin Tarrantino”. Scott Myers. Crave Online. August 22,2009.

0 Comments

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

- Anatomy of a Murder Notes

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed