|

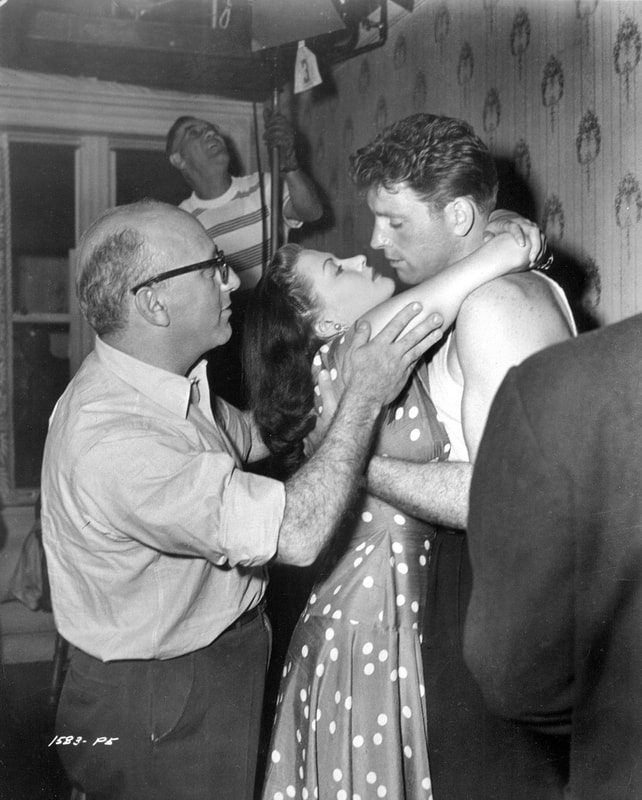

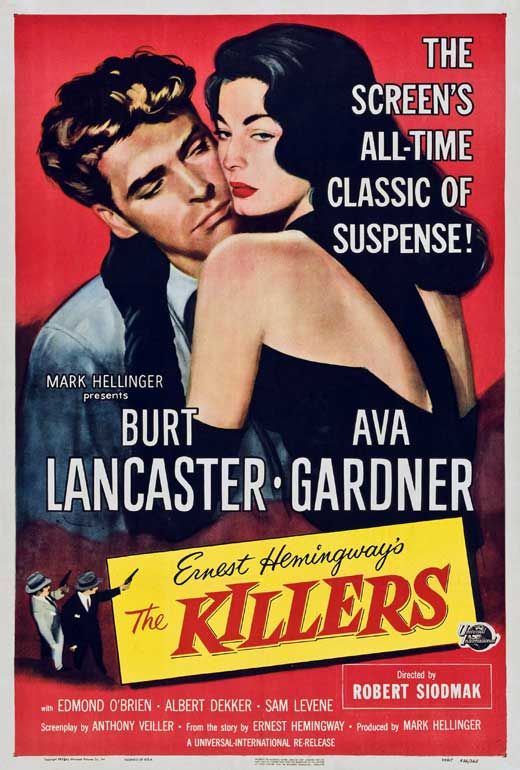

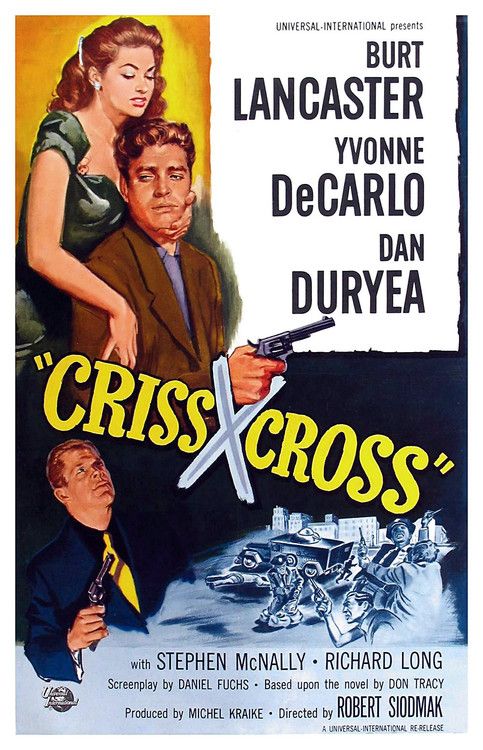

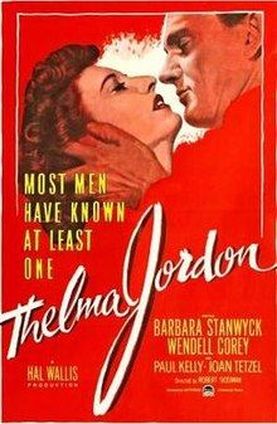

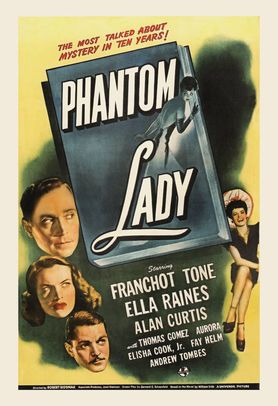

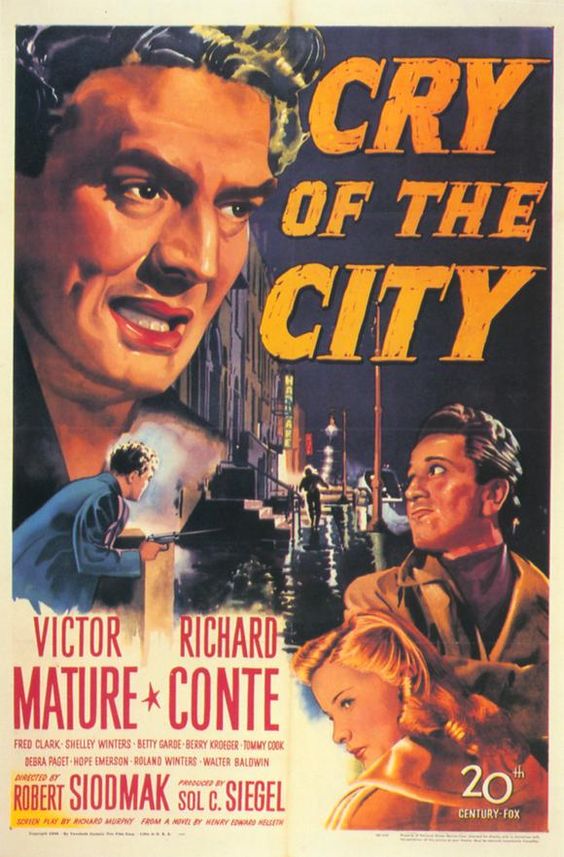

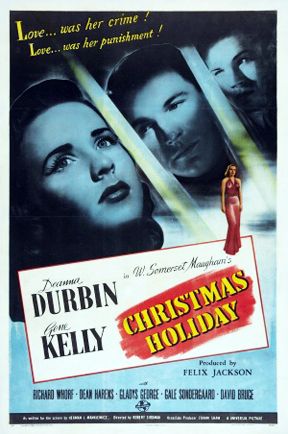

The Rationale: Robert Siodmak didn’t invent Film Noir. In fact, Film Noir was not even identified as a movement in film until the mid-Fifties (A Panorama of American Film Noir 1941-1953. Raymond Borde & Etienne Chaumeton). What Siodmak contributed to Film Noir style & the Film Noir ethos , however, is inmeasurable. Like Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang & others, Siodmak emigrated from Germany in the late ‘30s to avoid Nazi persecution. With them they brought the artistry of years of work at UFU, the German state film entity that thrived during the Weimar Republic between the World Wars, including expressionistic set design & lighting, a dark sense of the world & a love of American pulp Fiction. Siodmak was at the artistic forefront while in Germany, but it took him nearly 7 years of working in Hollywood to establish his bona fides as a director and create his first Noir masterpiece, The Killers (’46). In the meantime, Wilder had directed Double Indemnity (’44) & Lang had directed The Woman in the Window (’44) & Scarlett Street (’45). Siodmak, however, raised the level of the visual element of the movement by relying more on the play of light & dark within the frame, capturing pools of light surrounded by ink black darkness as a way of communicating not just the action before the camera, but often the mood and internal struggles of the characters themselves. Regardless of the cinematographer he used, for instance, his films had a consistent visual style based on composition, mood and tempo, which allowed them to be elevated beyond most similarly budgeted productions of the era. Robert Siodmak may not have been the first Noir director, nor the most prolific, but he was the best because he used the stylistic tools of the movement in heightened and more extreme ways to create visual feasts for the eyes, tension filled plotting for the mind & unforgettable characters for posterity. The Killers (’46) wasn’t Siodmak’s first Noir, but it is arguably the greatest Noir ever created (http://www.top10filmlists.com/top-10-noir-films-classic-era) and was called the “Citizen Kane (’41 Welles) of Noir” by author Jonathan Lethem. Based on an Ernest Hemmingway short story, The Killers is the story of an insurance investigator trying to solve the contract killing of an ex-fighter, known as “the Swede (Burt Lancaster). While the film is told primarily in flashbacks, recounted by a variety of characters, the opening scene, from which the entirety of Hemmingway’s short story takes place, may be as famous as the entire film. Out of pitch black night 2 men emerge, captured in pools of light, as they make their way to a lonely diner. Inside, they state their purpose of waiting for the Swede to show up so they can kill him. The dialogue exchanged in the diner is filled with menace, as the 2 men torment the staff & patron (Quintin Tarantino borrows broadly from the style of the John Huston infused script) & ends with the killers departing, sure they can find the Swede in his apartment. Even when warned, however, the Swede fatalistically accepts his death at the hands of the killers & sets the exploratory plot in motion as insurance investigator Reardon (Edward O’Brien) pieces together the Swede’s life. As the Swede’s story unfolds it becomes apparent that at the center of his trouble is Kitty Collins (Ava Gardner), the sultry girlfriend of crook Big Jim Colfax (Albert Dekker). In perhaps one of the greatest introductions in film history, Siodmak has Kitty slowly turn around as the Swede approaches the piano as she sings. Luminously glowing, Kitty/Gardner simply overwhelms the Swede, captured wonderfully on Lancaster’s face. For both Lancaster & Gardner, The Killers was their first starring roles and the meeting scene crystalizes the relationship & everything that comes after it in those 2 simple shots. The Swede never recovers & Kitty holds him in that rapturous trance until his death. Big Jim is in prison & the pair strike up a relationship, just as the Swede is dragged into a life of crime. When the Swede takes the fall for Kitty & ends up in jail, his love only intensifies, while Kitty returns to Colfax. A heist brings them back together, but a double cross, then a triple cross, seals the couple’s fate, complete with Kitty’s final plea from the dying Big Jim that he clears her name. She is evil incarnate, completely self -absorbed, guiding the Swede by the nose to protect & enrich herself. She is the ultimate femme fatale, destroying both of the men in her orbit and making The Killers the quintessential film in Siodmak’s canon. If Kitty Collins is the archetypal femme fatale, then Anna Dundee (Yvonne De Carlo) in Criss Cross (’49) represents a more nuanced version, but no less deadly. She also plays a hopeless simpleton, again played by Burt Lancaster, into committing a crime that significantly alters his life. That she once loved & was married to Steve Thompson (Lancaster) casts her duplicity in a wholly separate light than Kitty’s, but up until the very end it is wholly ambiguous. Their relationship is built on conflict, constant bickering & passionate love making, imbued with an animalistic quality that resonates in every scene they share. When Steve leaves town Anna hooks up with Slim Dundee (Dan Duryea), a low life criminal with a violent side. When Slim catches the couple together Steve concocts a plan to rob his armored car as an excuse for he & Anna’s afternoon rendezvous, setting in motion the violent conclusion to the story. The heist itself, opening with a God’s eye view crane shot from above is a wonderful conglomeration of orchestrated chaos shot by Siodmak to create first tension, as the crew gets in place, then mayhem as the smoke bombs create an foggy dreamscape detached from reality. The exchange of gunfire from within the smoke screen furthers the confusion, while heightening the tension & emphasizing Dundee’s duplicitous nature. Siodmak captures the robbery with a documentarian’s eye, in and amongst the thieves as the smoke swirls around. When Steve is hailed as a hero, for saving most of the money, killing or wounding several of the thieves & taking a bullet himself, he is filled with remorse and anger at Slim’s double cross on his double cross. Only the thought of a rendezvous with Anna can save him and unfortunately opens him up to make his greatest mistake. With one of the most famous closing shots in Film Noir, Steve & Anna are forever entangled together. The Spiral Staircase (’46) deviates from Siodmak’s typical work during the 1940’s, moving away from Noir to straight suspense/thriller. In it a serial killer stalks a small town, killing women with physical disabilities and he may be after the mute Helen (Dorothy McGuire), who cares for a bedridden spinster in an old mansion. Sharing the mansion are tow grown men, the son & step-son of Mrs. Warren (Ethel Barrymore), a nurse, a caretaker & his wife and a secretary, who just happens to be the current love interest of one son & the former of the other. The opening scene of Helen watching a silent movie, while upstairs a crippled woman is strangled, wonderfully sets up the unique visual elements that Siodmak brought to The Spiral Staircase. In a shot that predates Hitchcock’s Psycho (’60) by 12 years, the camera zooms in on the killer’s eye as he moves towards the victim and kills her. Its uniqueness is richly engaging & brings the viewer into the position of the killer (something Michael Powell also attempted to do in Peeping Tom-’60). It’s also jarring and is repeated 2 more times as the killer moves throughout the mansion. Siodmak & screenwriter Mel Dinelli set the entire movie over the course of one tension filled rainy night at the Warren’s mansion. The title staircase leads to a wine cellar and storage room that has low ceilings & walls that seem to press in as several people venture down. In setting up a great deal of suspense throughout the picture Siodmak was called a ‘new Hitchcock’, but as noted above in some ways he was a head of the master. When the killer is finally revealed in the final reel it both a surprise & a relief. If ever there was a queen of Noir it would arguably be Barbara Stanwyck. From Double Indemnity (’44) to Sorry, Wrong Number (’48) & Clash By Night (’52), Stanwyck embodied the essence of the Noir dame, whether as the pure Femme Fatale or as a victim of circumstance. Siodmak’s The File on Thelma Jordan (’50) leaves no doubt on which side of the Noir ledger she is most comfortable, however. As the lead character, Stanwyck exploits assistant district attorney Cleve Marshall (Wendell Corey) to first manipulate a crime scene, then to a jury, all the while creating uncertainty in her guilt. The fact that Cleve loves his wife & is a devoted father (albeit hen pecked by his father-in-law) has no bearing on Thelma’s ability to start an affair, move him towards familial disinterest & finally threatens his freedom and career. The dark mansion, where the murder takes place, is taken right from a gothic horror film, with dark wooden walls, over decorated furnishings & a helpless old maid, just rich enough to be murdered. While the house is always cloaked in darkness & surrounded by rain, an easy location to create Noir’s shadowy world, the courtroom, on the other hand is brightly lit and blandly appointed. It is in this contrast that Siodmak draws out Thelma’s duplicity. In the light she is vulnerable and small, but in darkness she is manipulative and sexy. Thankfully she maintains her web –like control for as long as the production code would allow! Charles Laughton is one of my favorite underappreciated actors. His work in Witness for the Prosecution (’57) & direction of The Night of the Hunter (’55) alone are enough to warrant my eternal praise, which is why his performance in The Suspect (’44) is so greatly appreciated. Phillip Marshall (Laughton) is a put upon manager who befriends a much younger woman (Ella Raines) & begins spending more time with her than with his shrewish wife (Rosiland Ivan). Siodmak & screenwriter Bertrand Millhauser paint the 2 relationships as diametric opposites, with a montage of enjoyable outings with the younger woman contrasted with the verbal tirade he receives every night when he returns home. When the wife discovers the innocent tryst she threatens exposure & she must die. The murder looks like an accident, but a dogged Scotland Yard detective (Stanley Ridges) considers Marshall as suspect nonetheless. When blackmail is introduced by yet another character a 2nd murder is committed, but Marshall has plans to leave the country, if only his conscience will allow it. Siodmak does a wonderful job of offering Marshal a better life with Mary (Raines), but it is the moments of tension & conflict that make The Suspect so enjoyable. The verbal banter between Marshall and detective Huxley (Ridges) is fraught with peril for the suspect, but each encounter ratchets up the tension. Similarly, when a dead body is stashed behind a couch just as a party breaks out there is edge of your seat concern for its discovery. Laughton, however, is the lynchpin here, perfectly melding with Siodmak’s style of a conflicted protagonist caught between what is legal and what is right. John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (’41) is often credited as the beginning of the classic Noir era and rightfully so, but 3 years later, when Siodmak made Phantom Lady (’44) many of the identifying traits of Film Noir had not been clearly established. Released 6 months before Billy Wilder’s seminal Double Indemnity (’44), Phantom Lady moved the Noir cycle more clearly towards German Expressionism, with a greater emphasis on dark versus light, oblique camera angles and a greater sense of fatalism in the storytelling. Where it also broke ground was in its use of a female protagonist (Ella Raines), who seeks out the phantom lady as the only alibi her boss has to save him from the hangman’s noose for allegedly killing his wife. As she pieces the bosses evening together, Siodmak builds tension by playing off the vulnerability of Raines as she pursues the killer & is stalked by him. The scene as she follows the barman home through the dark & rainy streets of New York, is a master class in suspense, shifting as it does between both people. When the barman slips behind Raines on the train station, ready to push her onto the tracks, there is nothing short of terror emanating from the dogged Raines. The use of shadows & natural sounds heightens the mood as one, then the other moves in and out of pools of darkness. Finally, when there is a confrontation it is like a crack of thunder shattering the tension. Similarly, Siodmak utilizes obtuse angles and the interplay of light & shadows, as well as quick rhythmic cutting to emphasize hep cat jazz drummer Cliff’s (Elisha Cook Jr) near orgasmic drum solo that he plays for Carol (Raines). The room is claustrophobically small, the lights cast odd shadows at peculiar angles & Raines/Carol shifts uncomfortably throughout, making the scene at the very least strange, but mostly overtly sexual, as the drumming & editing become more frantic. Finally, the very Noir climax captures the surprise killer in extremely focused lighting, with only the killer’s eyes visible in a strip of light. The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (’45) is on the twisted side of Film Noir and would have been ranked higher if Siodmak had been able to make the movie he wanted. Harry is a pattern designer who lives with his 2 sisters in the family mansion. One sister is meek and mild, while the other sister is coolly manipulative & outright cruel to her sister. Between them sits Harry, content to provide for his sisters, maintain a bachelor life & look at the stars…until Deborah Brown (Ella Raines) comes to town and sweeps him off his feet. Before long the couple is talking about marriage, but dominant sister Lettie (Geraldine Fitzgerald) will have no part of Harry moving out of the house, nor will Deborah settle in the house. In many of Siodmak’s work a romantic triangle emerges to drive the plot (think Slim/Anna & Steve in Criss Cross or Swede/Kitty & Big Jim in The Killers) & Uncle Harry is not different, although this time the triangle has a deviant twist. Lettie’s relationship with Harry has overtones of incest, as Lettie’s emotional reaction to Deborah’s presence exposes. She pines for Harry to return from work each day, she dresses provocatively when she feigns illness & draws him to her room & finally, she blocks his happiness by undermining his relationship, telling Deborah “we feel we know what’s best for Harry.” In order to free himself, Harry decides to poison Lettie, but his plan goes awry & subservient sister Hester (Moyna MacGill) ends up dead, with Lettie the accused killer. I noted that the final film is not what Siodmak envisioned, as his ending was nowhere near as tidy as what the studio and the Production Code office demanded. Without giving anything away, suffice it to say that The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry is a fine film for more than 95% of its run time, but to understand what could have been makes that 5% even more painful to watch! Siodmak did most of his early work at Universal, but he moved over to 20th Century Fox to make Cry of the City (’48), the 3rd in a series of urban thrillers, after Kiss of Death (H. Hathaway ’47) & Boomerang! (E. Kazan ‘47). Victor Mature plays Candella, a straight arrow cop out to capture family friend Martin Rome (Richard Conte) & solve the case of some missing jewelry. Unlike most Noir, where the story is often told in flashbacks or out of sequence, Cry of the City maintains a straight line narrative, even though it opens with the administering of last rights to the main character (Rome). Before he recovers, however, and escapes from the prison hospital, he is visited by a mysterious woman who Siodmak has literally appear from the darkness like an apparition. Siodmak utilizes lots of cramp interiors in Cry of the City, most of which are lit to divide the screen into areas of light and dark. Similarly, he often shoots through doorways to create frames within the frame, allowing for an illusion of depth, but really capturing a nesting doll effect that traps the subject in ever shrinking spaces. The Rome family’s apartment, full of hallways & rooms off rooms is particularly helpful in reflecting the twisted circumstances of Martin Rome. His life is one attempt at escape after another, each one leading to a more confining environment; the hospital bed, the hideout apartment, the backseat floorboards & the masseuse’s strangulation attempt. Siodmak rarely paints characters as purely good or evil & the 2 protagonists here, while existing on either side of the law both share a commonality of purpose. For Candella, it is saving Martin’s brother’s soul & for Martin it is saving his girlfriend Teena (Debra Paget) and creating a better life. For both men, however, it is a ‘by any means necessary’ MO that casts them as not purely good or evil. The Dark Mirror (’46) is a psychological thriller where Olivia De Havilland plays identical twin sisters who share a job, fooling everyone into thinking they are just 1 person. Trouble ensues when a man is murdered and witnesses identify one of the sisters as seen fleeing the scene. Siodmak & screenwriter Nunnally Johnson (The Grapes of Wrath ’40) explore more deeply the good sister/bad sister dichotomy from The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry. Initially, police detective Stevenson (Thomas Mitchell) attempts to create 3 way tension with the sisters, but he cannot break the sisters devotion to each other. When he brings in psychologist Dr. Scott Elliot (Lew Ayres), who happens to have a casual relationship with good sister Ruth, however, it becomes apparent that Ruth’s psychosis’ are deeply rooted in jealousy of her sister. DeHaviland & Siodmak clashed in creating the Terry/Ruth dynamic, with Siodmak wanting more of a dramatic break between them & de Haviland wanting to play Terry as a study of the breakdown of a schizophrenic mind. While the dual performance is fantastic, Siodmak’s intention towards a more psychological study remains dominant. Cinematographer Milton Krazner, who had earlier worked with Fritz Lang on Woman in the Window (’44) & Scarlett Street (’45), aids Siodmak in crafting a noir mis en sen through the use of shadow, particularly in the opening murder scene. The 2 further utilize mirrors to fully reflect the very Noir concept of the reflected being 2 sides of a single coin. In the climactic scene, Dr. Elliot even states it as plainly as can be when he says ‘that’s what twins are, you know, reflections of each other, just in reverse.” Deanna Durbin became famous in the late 30’s & early ‘40’s playing teenage innocents in frothy musicals like Three Smart Girls (’36) & Mad About Music (’38). When she was cast opposite Gene Kelly to play an upscale prostitute in Siodmak’s Christmas Holiday (’44) she couldn’t have gone further against type. Kelly, too, as the degenerate gambler & murderer, was also playing significantly against type, but here the combination is dynamic & allowed for both actors to stretch their wings. The story is broken up into 3 parts, with the middle portion told in flashbacks by Durbin’s prostitute pseudonym Jackie Lamont & recapturing the love affair between her & Robert Mannette’s (Kelly) love affair & marriage. She tells the story to officer Charles Mason who is layed over in New Orleans on Christmas eve due to weather. The first act is dedicated to laying out his backstory as a jilted lover on his way to kill the man who eloped with his sweetheart while he was away in the service. The third act takes place in the present after Mannette has escaped from prison, where he was sent after killing a bookie, and his quest to kill Jackie for being a prostitute. Within the second act, however, are all the twists and turns of a Siodmak Noir & elevate the movie to overcome the extended first act & the abbreviated third act. Mannette & Abigal (Durbin’s characters real name) live with his mother, but when he comes home one night with blood on his clothes the truth of the mother/son relationship becomes clear as he uncomfortably embraces her while trying to retrieve a wad of ill-gotten money. The awkwardness is noted in Jackie’s flashback when she says “Robert’s relations with his mother were pathological. He wasn’t just her son, he was her everything.” A clear a marker of incest as has ever been allowed by the Production Code censors. New Orleans is captured sublimely (albeit on studio sound stages) through a series of buildings with elevate walkways, ornate iron fence work that sometimes blurs the characters behind it & finally in the many characters that inhibit the brothel known as the Maison Laffitte. Robert Siodmak utilized his experiences working in Germany & France, as well as his emigrant sensibilities to sculpt & elevate his films during the 1940’s to a consistent body of work that reflected who he was. While he was sometimes viewed as nothing more than a contract director working within the studio system, presenting what was given him in a pedestrian manner, as reexamination of his work clearly shows otherwise. He brought style and meaning to, in some cases, mere B grade scripts. He coaxed the first great performances out of Burt Lancaster & Ava Gardner & career best performances out of Yvonne DeCarlo & Deanna Durbin. His lasting legacy, however, was implementing & enhancing many of the basic elements of Film Noir. His ability to capture mood and character through lighting and staging transcended the many top notch Noir cinematographers he worked with. His shorthand editing style also helped create tension and suspense over long periods of time, while not undermining the basic narrative flow of the story. He made all this his own, putting his personal stamp on story, image & sound, creating a wonderful body of work over a relatively short amount of time (1944-1950).

0 Comments

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Top 10 Lists

- My Top 10 Favorite Movies

- Top 10 Heist Movies

- Top 10 Neo-Noir Films

- The Top 10 Films of the Troubles (1969-1998)

- The Troubles Selected Timeline

- Top 10 Films from 2001

-

Director Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Film Noir Directors

- Top 10 Coen Brothers Films

- Top 10 John Ford Films

- Top 10 Samuel Fuller Films

- Jean-Luc Godard 1960-67

- Top 10 Alfred Hitchcock Films

- Top 10 John Huston Films

- Top 10 Fritz Lang Films (American)

- Val Lewton Top 10

- Top 10 Ernst Lubitsch Films

- Top 10 Jean-Pierre Melville Films

- Top 10 Nicholas Ray Films

- Top 10 Preston Sturges Films

- Top 10 Robert Siodmak Films

- Top 10 Paul Verhoeven Films

- Top 10 William Wellman Films

- Top 10 Billy Wilder Films

-

Actor/Actress Top 10's

>

- Top 10 Joan Blondell Movies

- Top 10 Catherine Deneuve Films

- Top 10 Clark Gable Movies

- Top 10 Ava Gardner Films

- Top 10 Gloria Grahame Films

- Top 10 Jean Harlow Movies

- Top 10 Miriam Hopkins Films

- Top 10 Grace Kelly Films

- Top 10 Burt Lancaster Films

- Top 10 Carole Lombard Movies

- Top 10 Myrna Loy Films

- Top 10 Marilyn Monroe Films

- Top 10 Robert Mitchum Noir Movies

- Top 10 Paul Newman Films

- Top 10 Robert Ryan Movies

- Top 10 Norma Shearer Movies

- Top 10 Barbara Stanwyck Films

- Top 10 Noir Films (Classic Era)

- Top 10 Pre-Code Films

- Top 10 Actresses of the 1930's

-

Reviews

- Quick Hits: Short Takes on Recent Viewing >

- The 1910's >

- The 1920's >

-

The 1930's

>

- Becky Sharp (1935)

- Blonde Crazy

- Bombshell ('33)

- The Cheat

- The Conquerors

- The Crowd Roars

- The Divorcee

- Frank Capra & Barbara Stanwyck: The Evolution of a Romance

- Heroes for Sale

- The Invisible Man (1933)

- L'Atalante (1934)

- Let Us Be Gay

- My Man Godfrey

- No Man of Her Own (1932)

- Platinum Blonde ('31)

- Reckless ('35)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- The Sin of Nora Moran (1932)

- True Confession ('37)

- Virtue ('32)

- The Women

-

The 1940's

>

- Casablanca (1942)

- The Story of Citizen Kane

- Criss Cross (1949)

- Double indemnity

- Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair

- The Killers 1946 & 1964 Comparison

- The Maltese Falcon Intro

- Moonrise (1948)

- My Gal Sal (1942)

- Nightmare Alley

- Notorious Intro ('46)

- Overlooked Christmas Movies of the 1940's

- Pursued (1947)

- Remember the Night ('40)

- The Red Shoes (1948)

- The Set-Up ('49)

- They Won't Believe Me (1947)

- The Third Man

-

The 1950's

>

- The Asphalt Jungle Secret Cinema Intro

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ('58) Intro

- The Crimson Kimono (1959)

- A Face in the Crowd (1957)

- In a Lonely Place

- A Kiss Before Dying (1956)

- Mogambo ('53)

- Niagara (1953)

- The Night of The Hunter ('55)

- Pushover Noir City

- Rear Window (1954)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red Dust ('32 vs Mogambo ('53)

- The Searchers ('56)

- Singin' in the Rain Introduction

- Some Like It Hot ('59) >

-

The 1960's

>

- The April Fools (1969)

- Band of Outsiders (1964)

- Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

- Cape Fear ('62)

- Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) Intro

- Dr Strangelove Intro

- For a Few Dollars More (1965)

- Fistful of Dollars (1964)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968)

- A Hard Day's Night Intro

- The Hustler ('61) Intro

- The Man With No Name Trilogy

- The Misfits ('61)

- Point Blank (1967)

- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg/La La Land

- Underworld USA ('61)

- The 1970's >

- The 1980's >

- The 1990's >

- 2000's >

-

Artists

-

Resources

- Video Introductions

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed